Stories narrated in a dramatic manner attract and engage the masses, especially those from the lower strata whose daily lives are filled with struggle. ‘Masala,’ ‘escapist fare’ offers them nostalgia, inspiration, strength and hope. For, the cinema crafted for them is kinder than their unchanging reality. This causal relationship between income class and preference for movies is rooted in the fundamental human needs.

Thus, in the super-hit Manmohan Desai films of the late 70s and early 80s—Amar Akbar Anthony, Suhaag, Mard, Coolie—Amitabh Bachchan as the ‘angry young man’ /all-powerful protagonist fought against the odds and always emerged the victor. In the era prior to that, the hero’s primary on-screen duty was to practise virtues and stay kind in spite of all the atrocities that he faced. Raj Kapoor therefore won the hearts of his adversaries in Jis Desh Me Ganga Behti Hai with his simplicity and forgiveness. And Rajesh Khanna played the happy-go-lucky victim of a fatal health condition.

Thus, in the super-hit Manmohan Desai films of the late 70s and early 80s—Amar Akbar Anthony, Suhaag, Mard, Coolie—Amitabh Bachchan as the ‘angry young man’ /all-powerful protagonist fought against the odds and always emerged the victor. In the era prior to that, the hero’s primary on-screen duty was to practise virtues and stay kind in spite of all the atrocities that he faced. Raj Kapoor therefore won the hearts of his adversaries in Jis Desh Me Ganga Behti Hai with his simplicity and forgiveness. And Rajesh Khanna played the happy-go-lucky victim of a fatal health condition.

One explanation for the rapid decline in recent times of dramatic movies, which are known to exaggerate strife as well as triumph probably to underscore and emphasize the underdog’s victory, is that, overall, audiences across geographies have seen rising incomes, and exaggerated versions of poverty are difficult to relate to. Even older audiences who in their childhood loved these predictable storylines on a colourful canvas have outgrown such movies with the passage of time and are unable to connect to them anymore. This is quite understandable. For, as one climbs up the social ladder, burning life-and-death issues sometimes cease to be the top priority, as the mind tends to be more concerned with personal lifestyle and less with the ideological dilemmas of the marginalized.

There are complaints about the extent of poverty shown. What needs to be analysed is whether the exaggeration was a technique to make the respective stories more saleable or was simply mirroring the times. Movies such as Do Aankhen Barah Haath, Ghayal, and Meri Jung did well at the box office as the protagonist’s story was believable. Many such wholesome entertainers saw successful remakes too in later years. Sholay saw its storyline being repeated in Karma. And Ganga Jamuna saw its reflections in several movies such as Deewar, Shakti, and Ram Lakhan. My Left Foot, a book that was adapted to an Oscar- Award-winning movie, is about Christy Brown, a real person suffering from cerebral palsy but who overcomes it all and emerges as an artist in his own right. The reason why these movies worked is not only because poverty was romanticized but also because sensitivity existed in a greater degree in those times.

There are complaints about the extent of poverty shown. What needs to be analysed is whether the exaggeration was a technique to make the respective stories more saleable or was simply mirroring the times. Movies such as Do Aankhen Barah Haath, Ghayal, and Meri Jung did well at the box office as the protagonist’s story was believable. Many such wholesome entertainers saw successful remakes too in later years. Sholay saw its storyline being repeated in Karma. And Ganga Jamuna saw its reflections in several movies such as Deewar, Shakti, and Ram Lakhan. My Left Foot, a book that was adapted to an Oscar- Award-winning movie, is about Christy Brown, a real person suffering from cerebral palsy but who overcomes it all and emerges as an artist in his own right. The reason why these movies worked is not only because poverty was romanticized but also because sensitivity existed in a greater degree in those times.

There are complaints too that the ‘good-versus-bad’ drama is way too predictable, and overdone. But the fact remains that this theme has not been fully explored. It must continue for as long as Indian society still includes a sizeable share of manual scavengers, rag pickers, and disabled slum-dwellers. If their stories are told well, audiences would be informed about the collective responsibility of a modern society towards its most vulnerable sections.

Furthermore, the conscious compulsion to be different is actually predictable creativity. Dangal is a classic example where there were no surprises or suspense elements but the story was told honestly and was told well.

Somewhere at the root cause of all deriding and mocking of the dramatic is insensitivity, which has a direct relationship with wealth. Drama simplifies and sometimes oversimplifies the message with several licenses. But from one perspective, it works well—for someone who is down in the dumps, it could well be the anchor most needed to get out of a storm. To deride the dramatic in our compulsive urge, therefore, may be to deprive the lesser-privileged from a potentially-inspiring tale.

[divider size=”1″ margin=”0″]

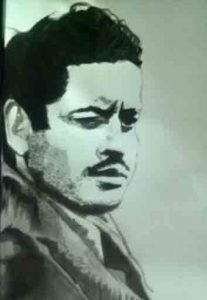

The artworks are by the author himself. He has done well over 350 portraits of film stars from the early to the present eras.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.