With the coming of sound in India in 1931, the rise of the major studios like Prabhat Film Company, Bombay Talkies, New Theatres – had played a significant role in the development of Indian Cinema. While in the eastern corner of India, Jyotiprasad Agarwala, trained at ufa, Berlin, and who submitted a film script The Dance of Art at ufa in 1930, an English translation of his own Assamese play Xunit Konwari, had heard of Himansu Rai (1892-1940). Rai went to Munich, Germany in 1924 to convince Peter Ostermeyer’s Emelka Film Company to produce his ambitious project The Light of Asia. When Emelka agreed to produce, it became a history as The Light of Asia (1925) was the first Indo-German co-production film. Later, they produced Shiraz (1928) and A Throw of Dice (1928-29) with typical Indian themes and settings.

UFA rejected Jyotiprasad’s script of The Dance of Art showing the reason that his story dealt with stereotyped Indian scenes and characters, and it would be risky to deal with such a production. If the script would have been accepted by UFA, undoubtedly The Dance of Art would have created another history in Indian cinema like The Light of Asia.

Back to Assam in 1930, he made a plan to make a film. Jyotiprasad wrote a letter to R.C.Rigordy, a photographer and cinematographer of Calcutta revealed that he wanted to make Joymoti as silent film with sound songs. He writes: ‘ I intend to make a silent film. But at the same time, I want to make a few songs in the picture ‘talking’. I think I can get done the talking part of the pictureby some other company. Excepting a few says, the picture will be exclusively silent…” i Then, Jyotiprasad made a contact with Sound Studio India Ltd, based in Bombay (now Mumbai). Responses from the different studios were almost same, and they refused to shoot the film in the interior places showing their technical difficulties. Even Jyotiprasad wanted to purchase the shooting equipment of his own and made a contact with Camera-Movie Company, Bombay. But that idea too did not materialize.

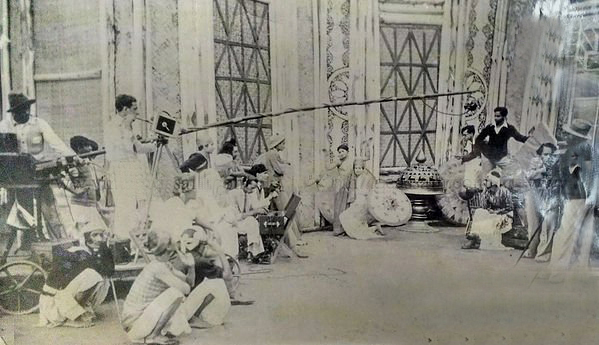

But finally Jyotiprasad established an impoverished film-studio at Bholaguri, on the bank of the river Balijan, a remote place, almost 300 km away from Guwahati. Named as Chitraban, the studio was set up in the midst of the lush green view of Bholaguri Tea Estate, owned by his family. It was a concrete platform, large in size with open-air enclosure of bamboo mats and banana stumps. It was the first open air studio established in India. They named the production company as The Chitralekha Movietone. The studio, equipped with laboratory and sound recording facility, was inaugurated by Jyotiprasad’s father late Paramananda Agarwala in 1934.

Jyotiprasad chose the drama Joymoti Konwori, by the eminent litterateur of Assam, Sahityarathi Lakshminath Bezbaroa for his film. His first Assamese film Joymoti, and also the first in North East, paved a way for the next generation filmmakers. Protagonist Joymoti’s silent but strong protest against the cruelty of the puppet king Lora Roja reflected how the apparently voiceless can have strong resistance. Moreover, the royal maid Seuti, veiled in man’s apparel, was riding on the horse and fighting with the enemy which suggests female power.

The film Joymoti was premiered on 10 March 1935 in the Rounak Mahal, Calcutta. Lakshminath Bezbaroa inaugurated the film, and the guests like Pramathesh Barua, Prithiraj Kapoor, Kundan lal Saigal, Devika Kumar Basu, Dhiren Ganguli, Phani Majumdar were present.

Jyotiprasad carefully chose non-professional actors for his film. Jyotiprasad wrote on 2nd Octobar 1934: ‘The picture as contemplated will be a new move in India. No professional actors and actress are recruited. All artists are scrupulously searched and discovered and only ‘types’ are selected following the Russian method.’

The setting of the film had to be designed showing the 17th century Ahom royal palace. Jyotiprasad himself designed the Ahom royal palace with bamboo and banana stem. Japi, made of tightly woven bamboo or sometimes cane, is predominantly used in the film – in the walls of the royal court – symbolically representing Assamese people’s cultural heritage. Assamese traditional symbols like xorai and banbota made of bell metal and brass are also predominantly used.

Jyotiprasad used Krishnasur (Krishna versus demon) dance in the opening scene of Joymoti. Jyotiprasad comments in an article titled Why the dance of Krishna-asur: ‘Krishna is the symbol of eternal beauty of human civilization. Demon is the ugly face of social evils. There is a continual clash between these two forces on the path of human progress. In the movie Joymoti – an unusual clash between culture and social evil is highlighted. On one hand, power hungry, war-monger, atrocious Laluk Barphukan who proceeded to celebrate political achievement with his evil designs and inundated the entire State with his lawlessness and injustice and, on the other hand, Joymati, the unique symbol of the State’s cultural power that stood up to counter this singlehandedly.’

Thanu Ram Borah, who played the role of Asur in the Krishnasur dance, recollected: ‘Jyotiprasad told me to dance in a very limited place and asked me to move my eyes with open mouth coming in front of the camera.” In an extreme close up shot, the Asura is seen moving his eyes. Jyotiprasad himself said: “ I saw an actor moving his eyes in a German film for the first time and probably, I would see it in my film for the second time.”

A typical Naga village with hills was constructed in Kharghuli of Guwahati, and one song with Dalimi was enacted there. After Kharghuli shooting, while returning to Bholaguri through the Brahmaputra river, Jyotiprasad was fascinated with the magical reflection of sunshine on the water and he instantly composed the song ‘Luitore Pani Jabi O boi/ Xandhiya Luitor Pani Xunuwali.’. Later, he incorporated it in Joymoti.

The choice of the story as the theme of his first film Joymoti, in fact suggests itself that he treated cinema as a vehicle for portraying the socio-political and cultural upheaval of the country rather than merely using it as a form of entertainment.

When Hindi and Bengali cinema were the crowd pullers in Assam, it was like going against the wave to make an Assamese film at a place where cinema had hardly been heard or discussed. Jyotiprasad adapted the story of Joymoti and moulded it to his own way. Characters like Gathi Hazarika were new additions to the existing story.

The first open air studio The Chitralekha Movie tone was equipped with laboratory and sound recording facility, Interestingly, in the day time, tea was manufactured, while at night, rehearsal was done in the factory .

Phani Sarma, who played the role of Gathi Hazarika in Joymoti was amazed to see the Chitraban, and thought “Is Chitraban a film studio or a film training institute?” Because Jyotiprasad engaged them in different activities of filmmaking like film developing, processing and printing, set designing so on and so forth. Actors helped one another in their make-up, set designing, and sometimes worked as a caretaker with the cameraman. Naren Bordoloi of Nagaon who played the role Lora Roja said in an interview that Jyotiprasad used to take a bamboo stick and if anyone made mistakes while enacting the roles, they were beaten with it. While Jyotiprasad was in UFA,Berlin, he learnt that an actor is not just an actor. He himself has to do his works.Training at UFA has taught Jyotiprasad this multifaceted aspect of filmmaking which he used it in his first Assamese film. Even Devika Rani who was trained at UFA, recollected how she learnt things differently.

“Training at UFA was a thorough and strenuous business. I first entered as an ordinary worker and was an apprentice in the make-up, costume and sets departments. I worked under their most famous make-up man and there were no other apprentices under him. I used to get the make up ready for all the great stars, assist in the washing and cleaning of brushes, hold the tray on the sets, look after wigs and hair dressing, go to the laboratories for tests. During training, every three days I was asked to write a note on the different make-ups used by the stars, why the lighting had to be done in a particular way, why for a particular close-up the lips had to be softened, and check on the progress.

Whatever department I worked in, my notes as a student had to be written, with progress jobs to do. For instance, it was not enough to know just how to make a set. I had to visit Universities to get the background and study the history and architecture of the period, and the manners, customs and ways of the locale of the picture. And yet, after two years of intensive general training and test, you were asked to forget it all, because you had become too mechanical ! You were asked to become yourself. ” ii

Search for the Heroine

Finally Aideu Handique as Joymoti was discovered by Jyotiprasad. Aideu Handique (1915-2002), was discovered in a remote village called Pani Dihingia Gaon, in the present Golaghat district by her relative Dimba Gohain. She was an illiterate village girl and was barely 15 years old when she acted in the first Assamese film Joymoti. Dimba Gohai planned to take her to Jyotiprasad. One day, he took her and her little brother to the river side Brahmaputra saying that he would show them a floating house on the river. It was, in fact a ship. Once they boarded on the ship, it took them to the other side of the river, and finally to Chitraban, the Bholaguri Tea Estate. “When I boarded the ship, it sailed down and after a day it anchored in a ‘foreign’ place,” said Aideu.iii Aideu knew nothing what was happening. Everything happened just in a wink !!! Jyotiprasad later sent for her father who was a school teacher. She agreed to act in the film, only when her father gave the consent. During the shooting days, she stayed with Jyotiprasad’s Khuri (Aunt). Aideu said that Jyoti Kakaideu (Brother) was like a father figure for her and taught her in details the inner meaning of a scene, how to walk, how to speak, how to look sad or happy. She said,

“Jyoti Kakaideu told me that Lai-Lesai (names of the two sons) would be snatched from my bosom. He said to me to feel as if they were your own sons and advised to express my emotions that way.”iv

She further said that ‘Jyoti Kakaideu did not use make-up on my face as my skin colour and face was very bright and red’.vi She fondly remembers an incident while enacting a scene in the film. She said that according to the script, Phani Sarma who played the role of Gathi Hazarika, was supposed to beat her to know the whereabouts of her husband Gadapani. She recollects: “Phani Sarma was supposed to beat me… and to tell you the truth, he drank a little bit of wine before enacting the scene! I was a healthy girl, and it was only later that I felt the wounds. I cried and fell down, and then I was hospitalized for a week. I was not given any rice but only milk.”v

The legacy Jyotiprasad Agarwala has left in Assam has been carried forward by Padum Barua, Dr, Bhabendra Nath Saikia, Jahnu Barua, and many filmmakers, and more recently a group of promising filmmakers like Rima Das, Deep Choudhury, Reema Bora, Jaicheng Dohutia, Suraj Dowarah, Kangkan Deka, Khnajan Kishor Nath. Nava Kumar Nath.

But Jyotiprasad Agarwala of Chitralekha Movietone like other Indian filmmakers -V. Shantaram P.C. Barua and Himanshu Rai pioneered the growth of Indian cinema, but still he remains ignored at the national narratives.

[divider size=”1″ margin=”0″]

End notes :

- i) R C Rigordy writes a letter to Jyotiprasad on 15th July, 1933

- ii) Malik Amita, Padma Shri Devika Rani , Filmfare 14th March 1952

iii) Goswami Sabita, ‘The First Lady of Assamese Cinema’ , The Assam Tribune 2002 (December)

- iv) Nirod Choudhury Asamiya Bolechabir Itihash, (Guwahati,Bani Mandir 1985) 55

- v) ibid

- vi) Bobbeta Sharma,The Moving Image and Assamese Culture, Joymoti, Jyotiprasad Agarwala, and Assamese Cinema (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014) 129

Well written write up. Hope, he will write a well researched book on Jyotiprasad.

This is an important article. Thank you for sharing with us.