This was around 1955. Ritwik Ghatak was in Bombay, sharing his living quarters with Hrishikesh Mukherjee. Producer Shashadhar Mukherjee had him employed at Filmistan Studios, writing stories and scripts for them. Ritwik had just been married to Surama Bhattacharjee. He wrote to his young bride, who was working at a school in the northeastern hill station of Shillong:

“…it’s upsetting when I see the way they work. Truth be told, there is no work at all, I just have to write a bit of rubbish once in a way and go sit in office from 10 AM to 5 PM…. I just have to grit my teeth and keep trying to earn some money. I don’t know if I’ll be successful, but nothing else is possible here. Doing good work, doing my kind of work, showing what I am capable of and trying to establish myself, all of that looks out of reach right now. I just have to find a way to earn a monthly salary….look, Lokkhi, this life is not for us. Working for money is not something I have done before and it’s disgusting to me. Somehow, if I can pay off my debt of around Rs.1000 and be in a position to pay Bhupathi 100 Rs. month for a year or so, I will leave all this. This can’t go on. I look around me and see that even people who earn three or four thousand rupees a month are not happy. But I have found peace in doing the kind of work I like without earning so much as a paisa.”

Having just married, the couple planned to start a new life, with her earning a salary as a school teacher, and him encashing his storytelling skills working in Filmistan. But the ‘job’ was tugging away at his gut. He was told he should try and write something that was more ‘Bombay-like’. Ritwik was disgusted. But he kept at it, trying to keep his head down and just do the work he was being paid for, like millions of people did every day – and still do. He was also biding his time till he could save enough and return to Calcutta and be back to ‘struggling’ as an independent artist. Struggle. A favourite word of the leftist intellectual, especially back in those days. And Ritwik Ghatak was a walking, talking, breathing embodiment of this.

He ended up righting stories for his friend and roommate Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s debut directorial venture, Musafir (1957) and for his revered Bimal Da’s Madhumati (1958). Bimal Da, who broke into the scene with Udayer Pathe/ Humrahi (1944), a production of New Theatres, Calcutta and marked for its unusual representation of caste disparity. And then, the moment he created his own banner, he created the seminal Do Bigha Zameen (1953), which was a spiritual descendant to Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948). It followed that the young rebellious filmmakers and playwrights would look up to him. Bimal Roy was a poster boy for them. Was Ritwik’s anguish also caused by this giant of a filmmaker hiring him and having him write a reincarnation love story? He indicates in other letters to ‘Lokkhi’, which was Surama’s nickname, a number of concepts that germinated in his head but had to be nipped in the bud because they were not commercial enough, not ‘Bombay enough’.

“I have planned a story for Filmistaan. I like it very much. An atomic research scientist falls asleep while doing his research, dreaming about a future world where a universal scientific community has taken shape. Of course, I have to keep space for a lot of song and dance and romance, and melodrama; I have to put in all the ingredients of a Bombay film.” He even wanted to consult legendary astrophysicist Dr. Meghnad Saha, so that his story had that ring of authenticity. But we know such a film never saw the light of the day. Shashadhar Mukherjee didn’t approve of it. There’s also an apocryphal story of him going to watch a trial show of Madhumati, which sealed the deal for Ritwik’s future career prospects in Bombay. He had just entered the theatre. The show had begun. One glance at the film and he knew this life wasn’t for him. There was no point in lying to himself anymore. He returned to Calcutta, bag and baggage. If he stayed back, he’d have seen the phenomenal success of Madhumati, and the untold riches and fame that would have obviously followed. And here’s the rub: Ritwik Ghatak hated ‘success’ with a vengeance. And in 2020, this is not any easier to understand than it was back then, in the 1950s. Every serious film director worth their salt has waxed eloquent on how Art is about not giving in to the system, about avoiding compromise at all costs. But Ritwik is probably the only filmmaker who took it all the way.

Upon returning to Calcutta, he made a bevy of films where he gave vent to his maverick spirit and uncompromising vision. Partition was a tragedy that had left deep scars in his soul. To him, it was a tragedy his fellow Bengalis, especially those from East Bengal, never quite recovered from. Each of his characters was reeling from the rootlessness he experienced all his life. But also his disillusionment and anger. In a scene from Subarnarekha (1962), Abhiram, who writes about the pain, filth and sadness he sees around him, has been turned down by an editor for the umpteenth time. He says to his wife, “Everyone is willing to suffer. You can see it all around. But try to tell them about it, and they run away.” Ritwik himself had similar things to say in his classic meditation on filmmaking, Cinema and I:

“My coming to films has nothing to do with making money. Rather, it is out of a volition for expressing my pangs and agonies about my suffering people. That is why I have come to cinema. I do not believe in ‘entertainment’ as they say it, or slogan mongering. Rather I believe in thinking deeply of the universe, the world at large, the international situations, my country and finally my own people. I make films for them. I may be a failure. That is for the people to judge..” And he didn’t care much whether the audience loved his work. Expressing what he wanted to say was more important. He said in an interview, “I have never made films for others. Truth be told, I don’t care if you dislike my films. I will do what I want to do, I will not go beyond that….Till I am alive, I can never compromise. Had it been possible, I would have done it much earlier, and would have sat pretty like a good boy. But I have not been able to do it so far, and nor will I ever be able to do it in the future. I will either live like that, or die trying.”

Whether it’s Bimal in Ajantrik (1958), Nita in Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960) or Ishwar in Subarnarekha, each one of his major protagonists go through unspeakable pain and yet don’t quite achieve what they set out to achieve. When Ishwar (Abhi Bhattacharya) tries to hang himself, his old friend Haraprasad (Bijon Bhattacharjee) barges in. Later Haraprasad tells him – “Our failure is complete. We cannot even kill ourselves.” And just like his characters, Ritwik kept writhing in pain. Surama left him and took the kids along. It was obviously impossible to live with a man like that, who refuses to make even the basic adjustments necessary for survival. He drank country hooch and smoked beedi. Nabarun Bhattacharjee, the son of his friend Bijon and ace litterateur Mahashweta Devi, once spoke of how Ritwik shamelessly asked money to buy alcohol. Nabarun had just 18 paise left in his pocket. “What can you buy with this?”…”One peg of country liquor!” pat came the reply. His friend Bijon Bhattacharya often was the most striking aspect of his films. He would play Ritwik Ghatak’s stand-in, and say with a lot of pathos the things that Ritwik wanted to verbalise himself. He steps in as Nita’s father in Meghe Dhaka Tara, one of the theatre actors in Komol Gandhar (1961), and Ishwar’s friend Haraprasad in Subarnarekha. A brilliant actor, Bijon would prance about the frame, fuming and spouting poetry, mythology, chants and everyday truths – every time the camera fell short to express the things Ritwik wanted to talk about.

In his last film Jukti Takko aar Golpo (Reason, Debate and a Story; 1974), Nilkantha (played by Ritwik himself) frustrates his wife so much with his idealism that she has to leave him. Much like his real life counterpart, Ritwik’s Nilkantha is left alone, licking his wounds and drinking himself to oblivion. There was a time he lived with Biswajeet Chatterjee (Bengali superstar Prosenjit’s father, he had a fairly successful run as a leading man in 1960s Bollywood). Biswajeet offered to remake Meghe Dhaka Tara, Ghatak’s most successful film, in Hindi. Plenty of moneys were offered. But Ritwik dragged his feet at the last hour. He refused for his film to be made in Hindi. It is said that even Rajesh Khanna, of all people, approached him with an offer, but was turned down. Ironically, Meghe Dhaka Tara inspired Tamil filmmaker K. Balachander to make his own version of it, Aval Oru Thodar Kathai (She is a Never-ending Story; 1974), with substantial modifications. The film was so successful that it gave rise to a franchise of its own, with it being remade in a number of languages, each version a huge box office draw. The Balachander version had a Hindi remake, Jeevan Dhara(1982) as well as a Bengali remake, Kabita (1977), featuring Kamal Hassan in his only appearance in a Bengali film. Ritwik of course didn’t live to see any of this. But he did live long enough to witness his protégé Mani Kaul being successful. By his own admission, the most glorious years of Ritwik Ghatak’s life were spent in the Pune Film Institute (FTII, Pune, now) where his shadow still looms large. Stories abound of how he used to sit under the Wisdom Tree with his talented chelas like Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, sharing with them the secrets of the universe. But when has a tiger changed its stripes? He used to turn up for screenings drunk, and when a good scene came up, he used to raise a din. It was for his students to make note of the great scene. He was made a director of the Institute. He was getting the recognition, the respect he craved, and there was money too. This would have turned the tide of his life. But he couldn’t stand it.

When Ritwik joined Surama in Shillong, she thought he was there to take them along to Pune. The news of him getting on well at FTII had filled her with hope. But he revealed he had resigned from his post and left Pune for good. Surama was crestfallen. Around the late 60s, Ritwik’s alcoholism had intensified and his mind had started unraveling. He reported hallucinating women covered with blood. Women he referred to as the ‘Spirit of Bangladesh’. He was being given electric shock therapy. Ritwik Ghatak was an extraordinary man, and his extraordinariness had finally caught up with him and he spiralled into insanity. There were extended periods of lucidity where he gave the impression of having been cured. It was during these intervals that he made Titash Ekti Nodir Naam (1973) and Jukti Takko aar Goppo, the latter representing exceptional heights of creativity. And yet Jukti Takko aar Goppo depicted him the way he was. Around early 1976, Ritwik Ghatak was admitted to Calcutta Medical Hospital. But Surama had seen too much of this by now. She refused to come. On 6 February 1976, Ritwik Ghatak’s journey culminated, finally. He was at peace.

Editor-filmmaker Arjun Gourisaria reminisced to online film magazine Cinemaazi that when he used to walk through the FTII campus as a new student, the seniors would say, “Zameen pe nazar rakh ke chal, yahan Ghatak chala karta thha!” (Keep your eyes on the ground, Ghatak used to walk here.) Such is the legend, the cult of the man. But despite all the aura around him as a filmmaker, Ritwik didn’t particularly care about the medium of film either. He said, “Looking back I can say that I have no love lost with the film medium. I just want to convey whatever I feel about the reality around me and I want to shout. Cinema still seems to be the ideal medium for this because it can reach umpteen billions once the work is done. That is why I make films—not for their own sake but for the sake of my people. They say that television may soon take its place. It may reach out to millions more. Then I will kick the cinema over and turn to T.V.!”

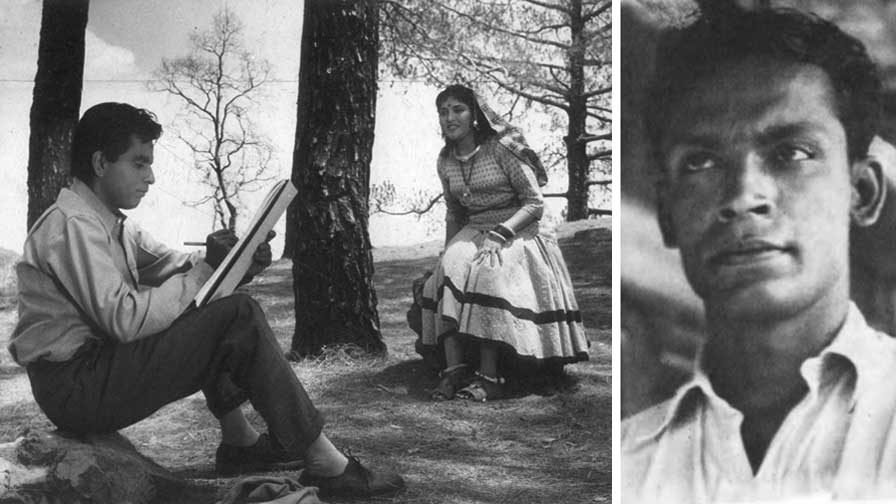

Ritwik Ghatak (Nov 04, 1925 – Feb 06, 1976)

https://filmcriticscircle.com/journal/ritwik-ghatak/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.