Kaifi Azmi — the Poet of Love, Revolution and Regeneration

Aaj ki raat bahut garm hava chalti hai

Aaj ki raat na footpath pe niind aa.egi

Sab uTho, main bhi uThun tum bhi uTho, tum bhi uTho

Koi khiDki isi divar men khul ja.egi

(A sultry wind blows tonight,

Sleep won’t visit the footpath tonight,

Rise, all; I’m rising too, you also rise, you too,

A window is breaking open in this very wall)

-Kaifi Azmi, ‘Makan’ (House)

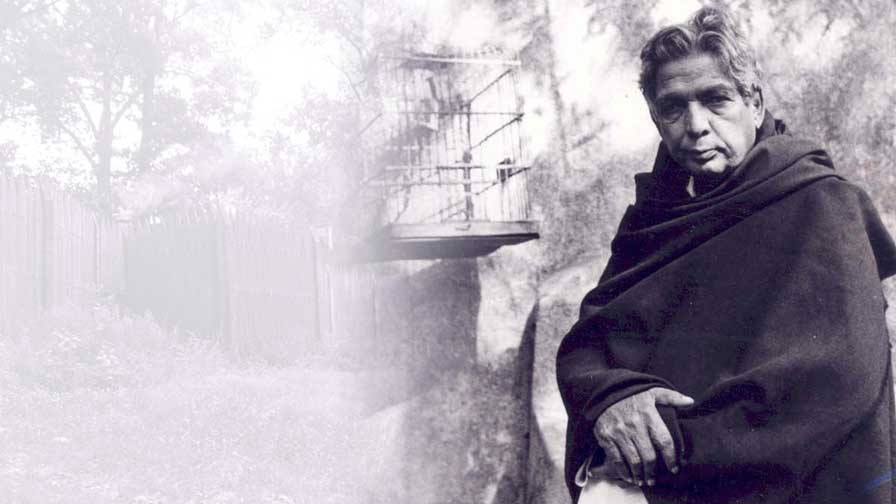

A great synthesizer of idyllic romance and revolutionary ideologies, of battle cries and patriotic hymns, and of tradition and modernity, Kaifi Azmi’s flexibility and versatility held him in perfect balance between modern Urdu literature and the Hindi film industry. The wavy hair falling over his shoulders, the never dying glint of his eyes, and the smile constantly playing in the curls of his lips together with his poise and baritone voice made him the cynosure of the poetic circle of his time; but all the same, he preferred to pass along unassumingly, shunning the mainstream for the margin, the centre for the periphery, and always voiced for the voiceless and supported their right to food, shelter and equality.

The lyrics that Kaifi Azmi penned for cinematic sequences too are equally embedded in true poetic exuberance combined with the silky splendor and lilt of Urdu. Even when isolated from the context of their respective cinematic narrative, his lyrics for films such as Kagaz ke Phool, Haqeeqat, Aarth, and Manthan emit the essential flavor of poetic concerto, in which specially chosen diction and images precede thought and meaning. Yeh nayan dare dare from Kohra evokes an arresting sensation of earnestness and Dheere dheere machal aye dil-e-bekarar from Anupama induces a mood of tenderness.

Chalte chalte from Pakeezah is another unforgettable lyric of sheer poetic intensity, trimly wrought, and strung through a selected set of recurring words and phrases that constantly defer and elude interpretation. The whole narrative of the lyric is woven round an incident of a chance meeting and this aspect of chance or casualness runs throughout the lyric by expressions such as yun hi (just like that), and koi (someone non specific). The poetic persona is either not aware of the identity of the person whom she met, or she chooses not to reveal it. But the memory of that meeting lingers; and though life moves ahead, some part of it stays back in the thrill of that meeting, causing the speaker to yearn and wait uncertainly. Yet, in spite of all uncertainty, the speaker says that there are stories, spilling all over, from that mysterious meeting, though she herself is unwilling to utter a word about it. This sense of ambiguity is accompanied by the image of candles burning out as the night of waiting (shab-e-intezer) gradually wanes and the speaker too seems to acknowledge that all waiting eventually runs its course someday, the aspect of indefiniteness being reiterated by the line kabhi hogi mukhtsar bhi (will be over at some point of time). She identifies herself with the candles that burn with her in longing and desire. But the lyric leaves no more clues as to how the waiting will be over. With fulfillment, or, will it just wither away unfulfilled? Again, the contrast of Chalte chalte (as the journey continued) and sar-e-raah (the whole stretch of the road) is remarkable. This building up of paradoxes, images and ambiguities make Chalte chalte one of Kaifi Azmi’s most memorable poems, with minimalist expression that engages all senses.

It is Azmi’s deep understanding of innate and perennial womanhood that enabled him to draw such a sensitive portrayal of the female psyche, be she a queen or a courtesan. This femininity, of course, has nothing to do with so called equality, emancipation and empowerment being voiced in today’s feminist movement. There is no way to know how much Azmi was aware of contemporary feminist debates; but his widely recited poem Aurat celebrates womanhood that accommodates contradictions and multiplicities, against the indivisible and unitary essence of manhood, and in tune with the recent feminist argument about men’s obsession with a stable self and women’s proneness to instability. In her discussion of the French feminist critic Luce Irigaray’s essay ‘This Sex Which is Not One’, Fiona Tolan comments, “Irigaray’s title is a heavily loaded pun; the woman is not the self (‘one’, or ‘I’) in masculine language, but at the same time, Irigaray is undermining the masculine binary system of positive/negative, by arguing that the female is not a unified position, but multiple: she is not one, but many.”1 Saying that a woman is not just an engaging story but also a reality and not just youth but also an entity, Azmi addresses women not from the usual male position of superiority, authority, pity and envy towards women, but in a joyful camaraderie to walk together with men, coming out of her “feminine mystique”2, that is, the societal construct or myth of femininity spun around her.

The poetic voice of the invisible and the oppressed, Kaifi Azmi shall be remembered and revered so long as the ideas of love, revolution, freedom and equality remain relevant.

References

- Tolan, Fiona. ‘Feminisms’, from Literary Theory and Criticism (ed. Patricia Waugh), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006.

- Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique, W.W. Norton, New York, 1963.

Photo courtesy

- Cover photograph: Official website of Kaifi Azmi

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.