The past decade saw a significant shift in the national box office, with dubbed films and remakes featuring unknown South Indian actors achieving massive success, often overshadowing original Bollywood productions banking on its leading stars. This trend is among the crucial socio-cultural aspects analysed by film scholar M. K. Raghavendra in his book under review, entitled “The Subject of the Nation and His ‘Others’ in Hindi Cinema: Gender, Religious, Caste, and Ethnic Identity As Difference”. The author draws on literary critic Fredric Jameson’s famous assertion that all ‘Third-World’ literary narratives should be interpreted as national allegories, arguing that post-colonial narratives bear public connotations because private life is much less separate from public concerns. Raghavendra extends this premise in his book, noting that cinema has gained sway over literary narratives in articulating the nation’s story.

Also drawing on political scientist Benedict Anderson’s concept of ‘imagined communities’, Raghavendra looks at the ‘imagined nation’ in Hindi cinema and identifies the hero chosen to ‘embody’ it. The hero’s personal story thus mirrors the nation’s existence as an allegory. This national subject is characterized as an upper-caste, Hindu, predominantly male archetype, often ‘surname-less’and ‘region-less,’ thus functioning as an ahistorical representative. Women, the marginalized categories, and minorities are presented as ‘others’ with separate stories for the issues dealing with them—but distinct from that of the nation. While this cinematic blueprint is not entirely unexpected, the author traces its origins to the rise of 19th-century Indian nationalism, as reflected in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s “Anandamath” (1882) and, in the first chapter, finds its basis to be elitist at its core.

This chapter on ‘Film Form and Ideology’ defines popular Hindi cinema’s stable, non-mimetic form. It prioritizes the relay of a pre-existing message or truism rather than reproducing the ambiguity inherent in reality. The primary message relayed in Hindi films sounds like traditional wisdom that upholds a seemingly universal value independent of historical context, for instance, loyalty to the family and obedience to it (Hum Aapke Hain Koun…! (1994)). Due to the focus on “universal truth”, character subjectivity is notably absent. The camera maintains an omniscient viewpoint, showing events as they transpired rather than through someone’s perception. The narrative unfolds as though a “first cause”—akin to karma, often a pivotal prehistory like the humiliation of the father in Deewar (1975), or a “seed” from Sanskrit drama—determines all subsequent actions. Romantic relationships do not progress through stages of interpersonal conflict (as in Hollywood) but are announced as “perfect” and “eternal”. Difficulties are caused by external agencies. The successful culmination of a romance (the transition from brahmacharya to grihastha or householder) is used primarily as a structural device to bring the film’s story to an end (closure), as “adulthood” is not an acknowledged stage of life in traditional Indian ashramas (life stages).

This entire form, stable since the silent era, is attributed to a hierarchical Brahminical tradition. The discussion calls it false consciousness and contrasts the form with Western mimesis, considering it as the normative standard. However, the possibility of a unique, coherent indigenous aesthetic—one that draws on the best of tradition—cannot be discounted, even if its expression lies outside the realm of popular cinema.

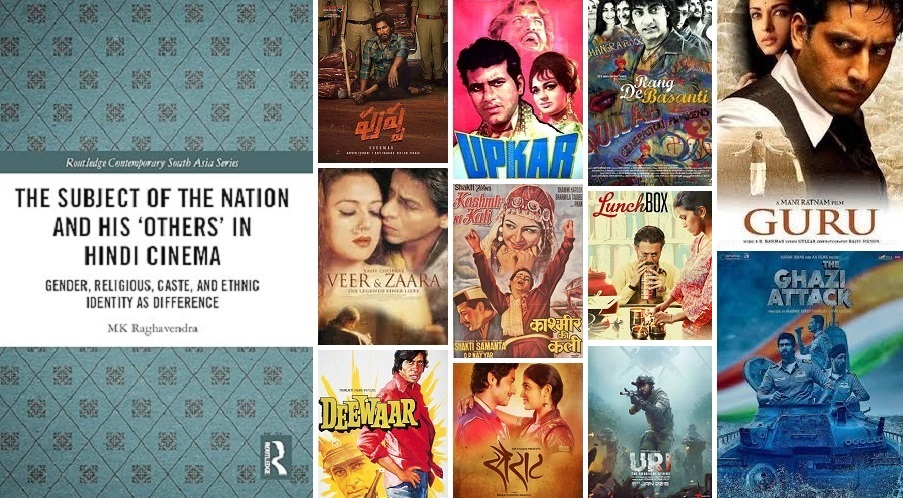

The author maps the male hero with distinct political eras: In the 1950s, stars like Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar, and Dev Anand portrayed diverse characters reflecting Nehruvian modernity and egalitarianism in films like Awaara (1951), (Babul, 1950) and Kala Bazar (1960) respectively. The 1960s saw romantic heroes signal national disengagement, e.g., Shammi Kapoor in Kashmir Ki Kali (1964), followed by the Angry Young Man in the 1970s, e.g., Amitabh Bachchan in Deewar (1975), emerging from Mrs. Gandhi’s radical politics. Post-1991, market logic defined personal destinies resembling karmic law, and the state recedes (Hum Aapke Hain Koun…! (1994)). It led to the New Millennium Anglophone/ Multiplex cinema which justified criminality for success (Guru (2007)).

The book’s perceptive analysis of Bollywood’s decline, set against new nationalist demands for patriotic cinema post-2014, is one of its important sections. As the author points out, this has led to a depletion of narrative possibilities, reducing them to the singularity of nationalism. Older patriotic films, like Manoj Kumar’s Upkar (1967), included multiple narrative threads, such as family life and agrarian relationships, alongside war. Unlike them, modern war films like The Ghazi Attack (2017) and Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019) have weakened or eliminated these other threads, suggesting an increasingly propagandistic role for cinema. The book discusses the pan-Indian success of dubbed South Indian blockbusters such as Pushpa (2021) and KGF 2 (2022), connoting “resistance to central authority,” and wonders whether this spells trouble for the inclusively imagined nation. While these films fill the void left by Bollywood’s patriotic fatigue, it is worth asking whether their defiant regional undertones would have come through in north India in the same way. In Hindi-dubbed versions, the regional versus national distinction is likely to be blurred, and their defiance may appear simply as local grit. Their anti-establishment or anti-authoritarian themes run counter to Bollywood’s nationalist preoccupations, complicating its national narrative—though ascribing “resistance to central authority” even in their pan-Indian avatar perhaps stretches the interpretation.

Film aesthetes might find it odd to view cinema through such a socio-political lens. They may echo the scepticism of Vladimir Nabokov, who famously questioned the value of fiction as a reliable source of information: ‘Can we expect to glean information about places and times from a novel?’ Extending this critique to cinema, one might wonder whether films can truly offer insight into a nation. However, the methodological approach of the book under review is grounded precisely in Fredric Jameson’s assertion that all ‘Third-World’ texts should be read as national allegory.

The book asserts that the portrayal of women remains fundamentally male-centric, evolving from strong pre-independence figures to victims of social pressures or state weakness, often needing male intervention for justice. Even modern, woman-centric films like The Lunchbox (2013) and Pink (2016) end up relying on and giving dominance to the male narrative voice. As for Muslims, historically positioned as ‘others,’ early film genres (like Historicals or Courtesan films) focused on upper-class life and forbidden love, reflecting social hierarchy. Post-Partition, the author argues that secularism became a form of minority protectionism, making these film narratives archaic by insulating them from internal issues like class conflict (Pakeezah (1971) and Nikaah (1982)). During the radical period of Mrs. Indira Gandhi in the 1970s, art cinema (supported by state intervention) provided different portrayals (Garam Hawa (1973) and Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro (1989)). The period following economic liberalization in 1991 initially saw Muslim identity become less significant in Hindi cinema (Rang De Basanti (2005)). After 2014, however, Muslim representation became distinctly politicized in films, with The Kashmir Files (2022) being a clear example.

The author analyses narrative patterns of films featuring Dalit heroes such as Masaan (2015) and Sairat (2016). They depict caste as mere irrational prejudice by using upper-caste actors, thereby denying the reality of the immense social gulfs and power imbalances inherent in its structural reality. The ‘social other’ evolves from the criminalized lower classes to politicians. It’s a sharp observation that Hindi film criminals are often portrayed as inherently criminal even before committing any illegal act. As for ethnicities in Hindi cinema, Kashmir is a law-and-order issue; South Indians gain economic respect, while North-easterners are overlooked. Finally, Pakistan is depicted as a morally inferior ‘brother led astray,’ questioning its democratic viability as in Veer-Zaara (2004).

This is the nineteenth book published by the prolific M. K. Raghavendra. It offers an insightful look at how India is imagined in Hindi cinema. The prose demands patience due to its scholarly depth, but the careful effort is richly rewarded by the author’s acute observations. Some interpretations may appear forced, suggesting an over-reliance on the national allegory framework. Nevertheless, while it is not aimed at film aesthetes, it demonstrates how film narratives reveal and perpetuate asymmetries of exclusion of ‘others’. Ultimately, the book not only analyses the recent success of South Indian blockbusters vis-à-vis Bollywood’s struggles but also provokes crucial questions about the future trajectory of Hindi cinema.

“The Subject of the Nation and His ‘Others’ in Hindi Cinema”, Routledge, 224 pages, Kindle edition ₹3,145.80, Hardcover ₹13,340

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.