Taking Stock of Seven Decades of Fostering Film Culture: Musings on V. K. Cherian’s book “Celluloid to Digital — India’s Film Society Movement”

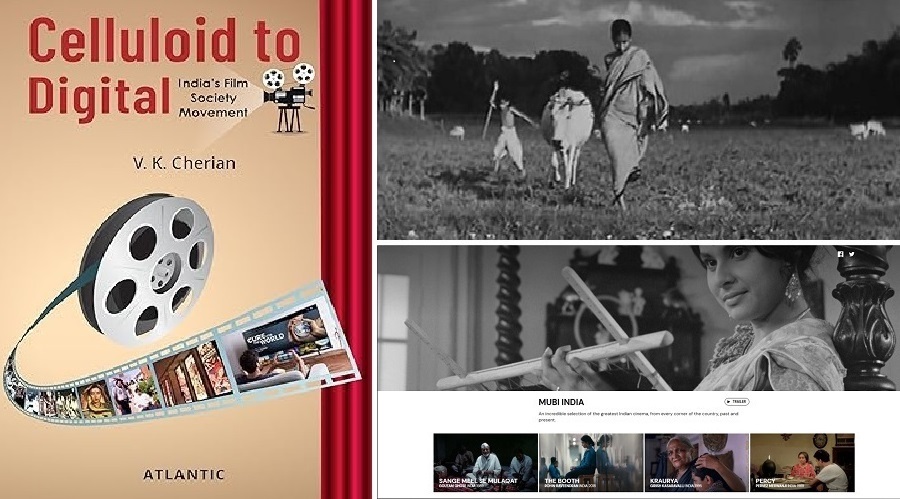

India’s film society movement mirrors the nation’s own journey, as captured in V. K. Cherian’s comprehensive 2016 book, “India’s Film Society Movement: The Journey and its Impact.” A revised edition by Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (2023) expands on the pandemic’s impact. Spanning seven decades, the book chronicles the movement’s history with fascinating, meticulously collected anecdotes. Exploring the interplay of technological shifts, economic changes, and government policies, it unveils their influence on this significant movement.

A film society activist himself, the author brings firsthand experience to the subject. He explores how Jawaharlal Nehru prioritized cinema alongside other cultural fields in his nation-building efforts. The central government’s 1951 S. K. Patil committee on films led to the creation of the International Film Festival of India (IFFI), the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), the Film Finance Corporation (FFC), and the National Film Archive of India (NFAI). However, the author poignantly highlights Nehru’s unrealized vision for a “Chalachitra Akademi.”

The book meticulously details the pioneers of the movement and the emergence of various film societies. While the Calcutta Film Society (founded 1947 by Satyajit Ray, Chidananda Das Gupta, and others) is often hailed as the first, the author sheds light on an earlier Mumbai society from the 1940s. Crucially, the Calcutta Film Society ignited the cinematic passion of Ray, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak, shaping them into filmmakers. Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) further revolutionized the movement, fostering appreciation of cinema as an art form.

While Pather Panchali’s success likely paved the way for a national film society organization, the book highlights Marie Seton’s crucial role. This British critic’s multi-city lectures spurred the 1959 formation of the Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI). The author compares Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s efforts in Kerala to Satyajit Ray’s in Bengal, illustrating how budding filmmakers cultivate audiences through film education. In neighboring Karnataka, the Suchitra Film Society emerged in Bangalore in 1971 under the leadership of H. N. Narahari Rao (who edited a book on the film society movement published in 2009) and his associates. Suchitra’s unique model, with a dedicated cultural complex, has enabled it to endure through present times. However, replicating this model elsewhere may prove challenging.

The granting of censorship exemption to the Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI) from 1966 facilitated access to films from consulates. However, as noted by the author, this positive step had its drawbacks in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period, there was a surge in people joining film societies, primarily attracted by uncensored films. Unfortunately, this trend deviated from the movement’s original purpose. A lack of critical rigor in appreciating films was evident among a significant portion of film society members. While some societies held discussions after screenings, a deeper understanding would necessitate journals with substantial writing on cinema. The author highlights “The Indian Film Quarterly,” a publication by the Calcutta Film Society. Other noteworthy publications include Bangalore Film Society’s “Deep Focus,” founded by George Kutty, M. K. Raghavendra, M. U. Jayadev, and yours truly.

Technological advancements are often seen as progress, but the shift from 16mm/35mm film to the digital era presented a challenge for film societies. While the transition eliminated the cumbersome process of transporting and projecting film reels, many cineastes still favor traditional film for its distinctive visual and tactile qualities over digital formats. However, a more significant consequence was the decline in audience numbers. The rise of readily available films online eroded the film society’s role as the sole source of alternative cinema.

The pandemic profoundly impacted film societies, much like other facets of society. In this second edition of the book, the author delves into how the pandemic altered film viewing habits. OTT platforms and YouTube brought films and videos directly to home theater screens and smartphones, shifting the communal viewing experience from social gatherings to personal spaces. Most film societies across the country felt the effects. The author gives the example of the online film society Talking Films Online (TFO) which responded to the pandemic by hosting discussions via Zoom every Saturday evening on a pre-announced film. Additionally, several other online forums sprang up during the pandemic.

Rather than lamenting the digital era, film societies can embrace it. One advantage of this era is the democratization of filmmaking, enabling anyone — even with just a smartphone — to create a film. This accessibility has inspired many film enthusiasts to explore filmmaking firsthand. However, the role of film societies extends beyond merely promoting film culture. They should serve as platforms for budding filmmakers and technicians, offering education not only in film appreciation but also in practical filmmaking. Additionally, organizing competitions in film criticism and mobile filmmaking, especially in collaboration with universities, can further nurture young talent.

The transition from a socialistic economy to an increasingly capitalistic one has occurred without adequate safeguards for promoting art cinema. The author delves into this issue, along with recent major policy shifts concerning cinema. As the film society movement faces multifaceted changes, creativity will be essential for its survival. The author suggests exploring avenues such as state units, campus film societies, and digital groups. The book would have benefited from more thorough editing. Despite that it serves as a valuable resource for various stakeholders — policy makers, filmmakers, film educators, film society organizers, and cinema students — to reflect on the history of India’s film society movement, gain perspective, and envision its future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.