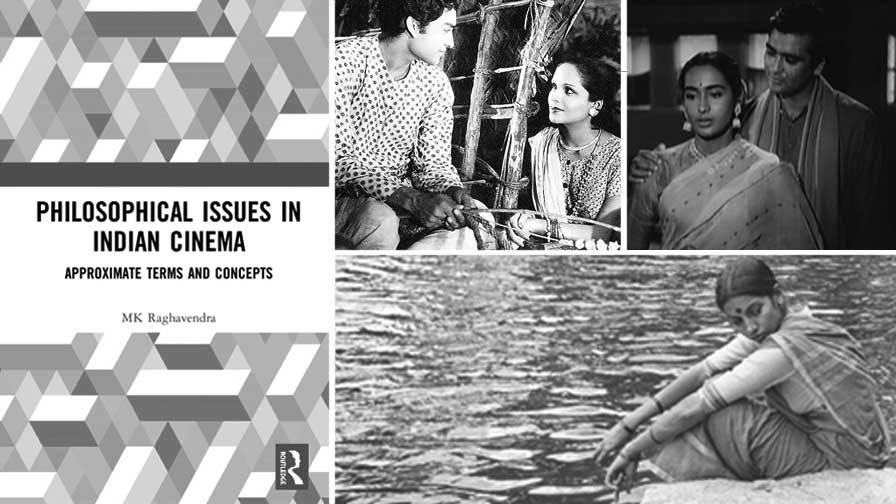

Despite mimesis as a narrative necessity and primary constructive principle of cinema being virtually absent in the lexicon of Indian filmmakers, their films work for the intended audiences, finds MK Raghavendra in his latest visitation of Indian films in the seminal book, ‘Philosophical Issues in Indian Cinema: Appropriate Terms & Concepts’.

The cinema of India is unique in many ways, and has travelled a long way since Dadasaheb Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra days. Further, there are largely two distinctive strands of cinema in India that run parallel and counter to one another—the wholesome-entertaining Friday releases in cinema halls and the aesthetics-driven genre that appeals more to the cerebral and nuanced expectations of differentiated audiences that populate film festivals. While the gravitas of a majority of wholesome entertainers lies in hero worship and heroine gazing, the chutzpah of art/alternative cinema lies in engaging a more cultured, elitist cine audiences with the larger socio-political discourse rousing the national collective conscience.

MK Raghavendra specialises in interpreting the diversified enterprising excursions of Indian filmmakers and reading the contextual meanings, metaphors, allegorical symbols and emblems in their visual representations. By doing so, he brings an insightful, intuitive, and interpretative discourse into Indian films. His method of mining meanings is an art all by itself.

His latest visitation, Philosophical Issues in Indian Cinema: Appropriate Terms & Concept, a compact 185-page hard bound book, makes for an illuminating and instructive read, in particular, for the initiated, unabashed cineaste who loves to probe beyond the peripheral context of a film that he/she watches, to understand what makes Indian cinema a key differentiator, and to be informed on what it lacks in the context of the global cinema coliseum. Thematically demarcated into 24 chapters, the book opens with the argument that Indian cinema woefully lacks the concept of mimesis in its approach and filmmaking.

In each chapter, the author lays out what constitutes philosophical issues in Indian cinema, while illustratively resting his arguments as regards appropriate terms and concepts “interrogating the vocabulary used in theorising about Indian cinema.” The idea being “to reach into the deeper cultural meanings of philosophies and traditions from which Indian Cinema derives its influences.” The basic objective, then, is to “re-examine terms and concepts used in film criticism and contextualise them within the aesthetics, poetics and politics of Indian cinema.” The book attempts to uncover whether there is an Indian way of filmmaking.

The author begins with the caveat that the book has no exalted ideas to offer about life or reality through cinema. He clarifies that this is neither a look at Indian film through the prism of Indian philosophical systems nor an attempt to deal with the philosophies of film. Rather, this exercise is merely “a revision/correction of the way Indian cinema has been understood in film studies or criticism.” He calls for a more holistic engagement and appreciation in the way Indian films, in particular, the popular, wholesome entertaining genre, are understood by their makers as well as the intended audiences they seek to serve. The idea stems from the fact that “Indian films belong to a different cinematic universe than those from America, Europe, and the Far East.”

The book explores and extrapolates through arguments and illustrations, “the way to understand Indian cinema, since that would help distinguish it from cinema outside of India,” with specific and contextual examples of popular films by noted Indian filmmakers from all over India, down the ages. The author enumerates that unlike what is understood in the Western context of philosophy “in terms of professional intellectual pursuit that can, be set aside at the end of the working day,” in Indian films, the term is more directly “associated with one’s personal destiny,” and “as an attempt to understand the true nature of reality in terms of an inner or spiritual quest.”

The book explores and extrapolates through arguments and illustrations, “the way to understand Indian cinema, since that would help distinguish it from cinema outside of India,” with specific and contextual examples of popular films by noted Indian filmmakers from all over India, down the ages. The author enumerates that unlike what is understood in the Western context of philosophy “in terms of professional intellectual pursuit that can, be set aside at the end of the working day,” in Indian films, the term is more directly “associated with one’s personal destiny,” and “as an attempt to understand the true nature of reality in terms of an inner or spiritual quest.”

“Largely constituted around a set of words or terms used in film scholarship/criticism by Indian film critics,” the primary purpose of the book is to be “devoted to notions connected with the terms in the title, examining the various aspects that make the significance of the terms clear for the Indian context.” The book is guided by a five-point agenda. The original meaning of the terms and the broad debates around them. What the terms mean in the context of Indian cinema from its origins onwards and how the notion has developed; alternatively, exploring the cultural specificity of a generic notion and its significance in India; the differences in the Indian employment of a component of cinema; certain terms that have specific Indian relevance; connections made within Indian culture as a body to explain the development of a phenomenon and the issue of ‘ideology,’ which becomes relevant when certain notions, such as nation, gender and dharma, are implicated.

The chapters have been classified according to terms and terminologies. Each goes on to elaborate their associations and understanding in the Indian context. These being Realism and Reality; Content, Interpretation and Meaning; Casualty; Genealogy and Family; Romance and Marriage; Melodrama; Faith and Devotion; Fantasy; Station and Hierarchy; Humour or Comedy; Character and Individuality; Genres; National Cinema; Regional or Local Cinema; Orality and Literacy; Film Music; Film Art and the Avant-garde; Stardom; Place and Time; Ethics and Morality; Gender Radicalism or Activism; Marginalisation, Oppression and Disadvantage; and Patriotism.

The book meets its ultimate aim of “bridging the gap between the academic study of Indian film and filmmaking practice in India.” Hence, it would be a futile exercise to go in for an illustrative manner how each of these concepts / terms have been dealt with in detail and deliberated upon. For that would not leave much for the individual imagination and ingestion of the reader who would love to have an unfiltered, unbiased read. I would like to state however that this new seminal book on Indian Cinema is not only a welcome addition to the few others that have preceded it, but also opens a whole new vista on how to actually watch, read, and understand Indian films and their filmmakers’ own idea of cinema. It ought to also aid and assist similar scholarly/academic exercises into the world of Indian films, their very many quirks and quibbles and allow the reader to understand what makes Indian films so Indian.

Several readings would be required by both the initiated and uninitiated to appreciate and assimilate the arguments that Raghavendra sets forth to substantiate his clinical claims. In conclusion: though each chapter has a short recap of the gist of the theme that has been taken up and talked about, one feels a bit more elaboration on the films cited as examples and illustrative explanation would have made the book a must-possess one for the cineaste bibliophile.

philosophical philosophical

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.