The 29th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), held in December 2024, witnessed a record-breaking attendance of 13,000 delegates—arguably the highest for any film festival in India. The book by V. K. Cherian, “Noon Films & Magical Renaissance of Malayalam Cinema” published by Atlantic Publishers & Distributors in 2025, examines the renaissance of Malayalam cinema and sheds light on the cultural ecosystem that fosters Kerala’s vibrant cinema culture. As the author emphasizes, Malayalam cinema has, from its inception, been deeply intertwined with social themes. Unlike the early films in other parts of India, the pioneering Malayalam silent film Vigathakumaran (The Lost Child, 1928) avoided mythological narratives. Subsequent Malayalam films continued in this vein, emphasizing social dramas. Building on this distinctive approach, the book explores the groundwork that catalysed the remarkable renaissance of Malayalam cinema from the 1970s onward.

The library movement in Kerala, spearheaded by P. N. Panicker, transformed the state’s literacy landscape. The author highlights Panicker’s remarkable efforts in establishing countless libraries across Kerala, fostering a culture of reading and intellectual growth, and playing a key role in achieving the state’s high literacy rate and broader development. Examining how left-wing organizations utilized theatre, cinema, and literature for political outreach, the author cites the play “Ningalenne Communistakki” (You Made Me a Communist), which was later adapted into a film. This pivotal moment set the stage for the emergence of three significant figures who became catalysts of the renaissance.

The author identifies the catalysts dubbed the “A Team” by Malayalam poet Dr. Ayyappa Paniker: Adoor Gopalakrishnan, G. Aravindan, and John Abraham. Their contributions to Malayalam cinema are portrayed as cornerstones of Indian New Wave cinema, also known as parallel cinema. Although this movement often centred on social critique, Adoor and Aravindan ventured beyond its boundaries. Even John Abraham, in his final film Amma Ariyan (Report to Mother, 1986), adopted a different approach to modernity, signalling a broader creative scope within the New Wave.

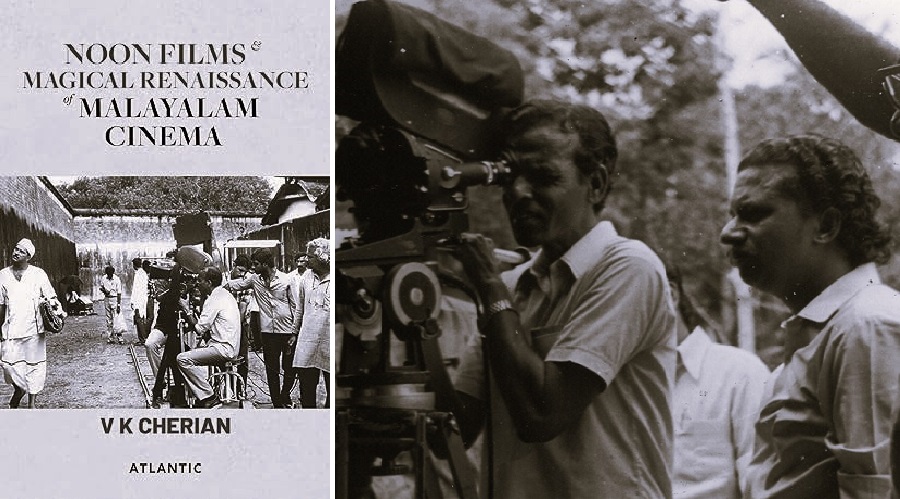

Among the esteemed A Team trio, Adoor Gopalakrishnan emerges as a trailblazer in Kerala’s film society movement, founding the transformative Chitralekha Film Society. This initiative, the author notes, mirrors Satyajit Ray’s profound influence on Bengali cinema. Adoor’s legacy expanded further with the establishment of the Chitralekha Film Studio in Thiruvananthapuram, a bold move during an era when Chennai dominated film production. Significantly, the author emphasizes how this step enabled the Malayalam film industry to shift its base from Chennai, fostering a unique identity free from Chennai’s commercial influences. Following the commercial success of his second film, Kodiyettam (The Ascent, 1978), Adoor challenged industry norms by ensuring his films were screened in three shows daily, rejecting the practice of relegating art films to noon slots—a practice that earned such films the moniker of “noon films,” referenced in the book’s title.

The book pays tribute to General Pictures’ Ravindranathan Nair, who patronized Malayalam art cinema by producing five films by Aravindan, and some of the later works by Adoor and M.T. Vasudevan Nair. The interview with Issac Thomas Kottukapally, who collaborated with Aravindan on three films, highlights Aravindan’s creative genius. The third member of the A Team trio, John Abraham, was also an FTII alumnus like Adoor. His second film, Agraharathil Kazhuthai (Donkey in a Brahmin Village, 1977), is a landmark in Tamil cinema. The author references Abraham’s thoughts on conceiving the idea of a Brahmin raising a donkey within a Brahmin colony. It is worth noting that the scriptwriter Venkat Swaminathan’s knowledge of the Tamil poet Subramania Bharati’s life and work significantly influenced the film. For his swan song, Abraham spearheaded the formation of the Odessa Collective, raising funds through grassroots efforts by traveling to villages and collecting donations from the public.

The final chapter examines the most significant contribution to Malayalam cinema by the eminent author, screenwriter, and film director M.T. Vasudevan Nair, who passed away in December 2024. His film Nirmalyam (Remains/ Yesterday’s Offerings, 1973) stands as a major milestone in Malayalam cinema history, yet it hasn’t received the recognition it truly deserves. It is fitting that Cherian has analysed this film in detail while paying tribute to M.T. as a towering figure. The book raises an important question about the lack of a new generation of filmmakers in Kerala comparable to the legendary A Team trio, though it doesn’t delve deeply into this issue. Despite some photographs in the book appearing elongated, it provides an insightful account of the renaissance of Malayalam cinema. After reading it, Kerala’s vibrant film culture—evident in the overwhelming number of delegates at IFFK 2024—becomes more comprehensible. Cherian’s exploration of this renaissance highlights the heights Kerala has achieved in the seventh art and underscores its enduring cultural significance.

VK Cherian, “Noon Films & Magical Renaissance of Malayalam Cinema,” Atlantic, 183 pages, Rs. 806/-

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.