Rishi Kapoor — Tujh mein kya hai deewane

A Bengali film buff growing up in 1980s small town India was overwhelmed with a plethora of influences. On the one hand there was the Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalani universe. Sunday afternoons were about “regional cinema”, where one was gradually getting exposed to names like Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Aravindan. And the works of Ray, Ghatak and Mrinal Sen were like a rite of passage for any Bong kid. We were of course bored to death with some of it but unwittingly, it was all seeping into our bones.

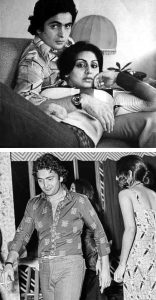

On the other extreme end were Sunday evenings and VHS sessions. While Amitabh Bachchan was like this benevolent God who kept on giving, he was less ‘accessible’, only to be found on video cassettes. For some reason, the national broadcaster rarely showed his films. The weekly shows on Sunday evenings (and later Saturdays and Tuesday afternoons) were reserved for Dev Anand, Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra, Joy Mukherjee, Biswajeet and… [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]Rishi Kapoor[/highlight]. While Bachchan had completely engulfed us, Rishi was the only other actor we truly enjoyed watching on screen. That smile could melt mountains. Bachchan with his swag and super-heroic invulnerability was a natural pull for kids our age, but Rishi managed to keep us engaged without any of these shenanigans. Because he was, contrary to popular (including his own) perception, a great actor even back then.

Adaakari

The mainstream Hindi film industry (“Bollywood” as a term wasn’t in circulation yet) was experiencing its worst phase back in the 1980s. So much so that many were declaring it dead. The middle class had all but given up on this form of entertainment, barring reruns on TV and video rentals. Nobody went to theatres anymore. Precious few films were able to recover their investment, even fewer reported hits at the box office. In the middle of this dry spell, Rishi Kapoor had a blockbuster in Nagina (1986).

The mainstream Hindi film industry (“Bollywood” as a term wasn’t in circulation yet) was experiencing its worst phase back in the 1980s. So much so that many were declaring it dead. The middle class had all but given up on this form of entertainment, barring reruns on TV and video rentals. Nobody went to theatres anymore. Precious few films were able to recover their investment, even fewer reported hits at the box office. In the middle of this dry spell, Rishi Kapoor had a blockbuster in Nagina (1986).

It was around this time that Rishi appeared in an interview for a Canadian television channel, which remains his only televised interview from that time.

”Jo cheez badi routine ho, usey aap ek novel tareeke se karke dikhaaye, uss cheez ko main bahut maanta hoon kyonki main khud ek spontaneous kism ka actor hoon”

He was, of course, referring to his approach to acting. Nobody at the time bothered too much about “the craft”. Nobody spoke about it, nobody wanted to hear about it. But here Rishi Kapoor, a “commercial cinema” actor, was talking about his “craft”. And this brings to light another aspect that was unique about that era.

Like in the rest of the world, the cinema of India was undergoing a shift in the 70s. A commitment to realism and what was seen as an emphasis on substance rather than form, gave rise to the Parallel Cinema movement. While its foundations were laid in the 50s, the movement gained wide acceptance in the 70s and 80s with the likes of Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Saeed Mirza, Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul doing their thing. This created a schism between the “commercial” cinema of the day and the so-called “art films”. These categories were neatly divided and the filmmakers and patrons of either kind of cinema would scoff at the other. But a curious fallout of this was that the so-called commercial cinema actors—like Rishi Kapoor—were seen with derision. Since they sang and danced and fought, they were perceived as bad actors. And that is what Kapoor was referencing in his interview. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Mainstream Hindi cinema has had a lingua franca of its own that it has evolved over the years. And while it cannot be blamed for making the audience “think”, it has left indelible impressions on the Indian psyche. It exists in its own Universe, with its own Reality. Loud, gesticulative acting is a hallmark of this kind of cinema. But there are some actors who have—while staying true to this universe—figured out their own “method” of infusing their performances with a certain sense of naturalism. Sanjeev Kumar, Ashok Kumar, Rekha and Rishi Kapoor are prime examples. Rishi for one has never dabbled in serious cinema—with the exception of the very unsure Ek Chadar Maili Si – and nor did he actively partake in the Kapoor family tradition of theatre.

But pick up the silliest of titles from his filmography, and Rishi’s acting in it is characterised by a sincerity that is present in some of his better known work as well. Consider Tawaif (1985), a B.R. Chopra film where Rishi plays Dawood, a wannabe writer who ends up having to live-in with a courtesan when she lands on his doorstep one night. Playing the template Muslim youngster commonly seen in “Muslim Socials” those days, not only is his Urdu diction flawless, he plays the part with a felicity mostly seen in actors trained on the stage: using space efficiently, interacting with props, economy of movement, impeccable timing. And the same elements can be seen in Ravi Tandon’s Rahi Badal Gaye (1985), where he plays dual roles, one of them visibly older. Rishi uses merely his body language to convey one person to have seen more years and the other being more effervescent and youthful. And then there was Duniya (1984), where he was pitted against Dilip Kumar. All these were uni-dimensional characters cut-out from cardboards. He almost never had meticulously written roles. But Rishi played them with a vitality not even expected of him in these parts. If you see him in these roles, it is inconceivable that he was doing multiple shifts a day, hopping from set to set.

But pick up the silliest of titles from his filmography, and Rishi’s acting in it is characterised by a sincerity that is present in some of his better known work as well. Consider Tawaif (1985), a B.R. Chopra film where Rishi plays Dawood, a wannabe writer who ends up having to live-in with a courtesan when she lands on his doorstep one night. Playing the template Muslim youngster commonly seen in “Muslim Socials” those days, not only is his Urdu diction flawless, he plays the part with a felicity mostly seen in actors trained on the stage: using space efficiently, interacting with props, economy of movement, impeccable timing. And the same elements can be seen in Ravi Tandon’s Rahi Badal Gaye (1985), where he plays dual roles, one of them visibly older. Rishi uses merely his body language to convey one person to have seen more years and the other being more effervescent and youthful. And then there was Duniya (1984), where he was pitted against Dilip Kumar. All these were uni-dimensional characters cut-out from cardboards. He almost never had meticulously written roles. But Rishi played them with a vitality not even expected of him in these parts. If you see him in these roles, it is inconceivable that he was doing multiple shifts a day, hopping from set to set.

And that’s why back in 1987 when his colleagues never spoke of such things, Rishi said in that interview: ”Main koi designed, created ya koi engineered acting nahi karta hoon. Main inn cheezon ko maanta nahin hoon. Jaise cheezen aati hain woh kar leta hoon, jo nahin aati woh nahi kar paata..”

Doosra Janam Rishi Kapoor

Around the year 2000, a new generation of filmmakers were bringing about a change in the way mainstream cinema was made. The parallel cinema movement had all but died, leaving offsprings in the shape of prodigious directors like Anurag Kashyap, Imtiaz Ali and Vishal Bharadwaj. Ashutosh Gowariker and Farhan Akhtar were demonstrating that socially conscious and realistic cinema can be made without alienating those seeking entertainment in the movies. The two cinemas were coming closer and closer until inevitably, they were fused together.

In this new world, “commercial actors” like Rishi Kapoor who had never set foot inside FTII or worked with Gulzar or Hrishikesh Mukherjee, should have found themselves at sea. But something unexpected happened. It was like he had suddenly been set free. All those years of animated gestures and loud dialogue deliveries and the flamboyance seemed to have been a solid grounding for the eccentric parts he was expected to play now, especially Romi Rolly in Luck By Chance (2009), Santosh Duggal in Do Dooni Chaar (2010), Rauf Lala in Agneepath, and the grandfather in Kapoor & Sons (2016). Notably, the new breed of directors employing him now had all grown up on the same commercial masala films Rishi Kapoor was a part of. They were all film buffs—and smart ones at that, so they knew how to play to his strengths.

In this new world, “commercial actors” like Rishi Kapoor who had never set foot inside FTII or worked with Gulzar or Hrishikesh Mukherjee, should have found themselves at sea. But something unexpected happened. It was like he had suddenly been set free. All those years of animated gestures and loud dialogue deliveries and the flamboyance seemed to have been a solid grounding for the eccentric parts he was expected to play now, especially Romi Rolly in Luck By Chance (2009), Santosh Duggal in Do Dooni Chaar (2010), Rauf Lala in Agneepath, and the grandfather in Kapoor & Sons (2016). Notably, the new breed of directors employing him now had all grown up on the same commercial masala films Rishi Kapoor was a part of. They were all film buffs—and smart ones at that, so they knew how to play to his strengths.

But this wasn’t a 2.0. It was the same set of skills, he was just employing them more consciously. He was more liberated. He took flight. Like he wrote in his autobiography ‘Khullam Khulla’, acting to him was ‘putting in effort to show effortlessness’. Unlike most movie critics and reviewers, Rishi Kapoor’s fans were not shocked or even surprised at what he was able to do now. We always knew. We were just having a ball seeing him have a ball.

This year he was about to reinterpret Robert De Niro’s role from The Intern, and team up with Juhi Chawla after 20 years for a film called Sharmaji Namkeen.

And the man had hardly even reached his prime. For all we know, Rishi Kapoor was just getting started.

[divider text=”Go to TOP” size=”1″ margin=”0″]

IMDB link of Rishi Kapoor

[youtube_advanced url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q7ds8oM_u70″ width” width=”300″ height=”200″ responsive=”no” controls=”alt” autoplay=”no”]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.