In the long history of Indian cinema there have been very few film directors who could be called as being possessed of genius minds. Dada Sahib Phalke was in that realm. He founded the film industry in India, stamping his image in all departments of film making. Satyajit Ray was another person. SS Vasan, in my view, was another. They had a wide repertoire of achievements and creativity. But the world also pulled in a young man from Rajasthan into this category—one who had very little to show to his generation but was a totally original artist.

The commercial film fraternity will not react to a name of Mani Kaul, but for any film student Mani Kaul rings the bell with great admiration and veneration.

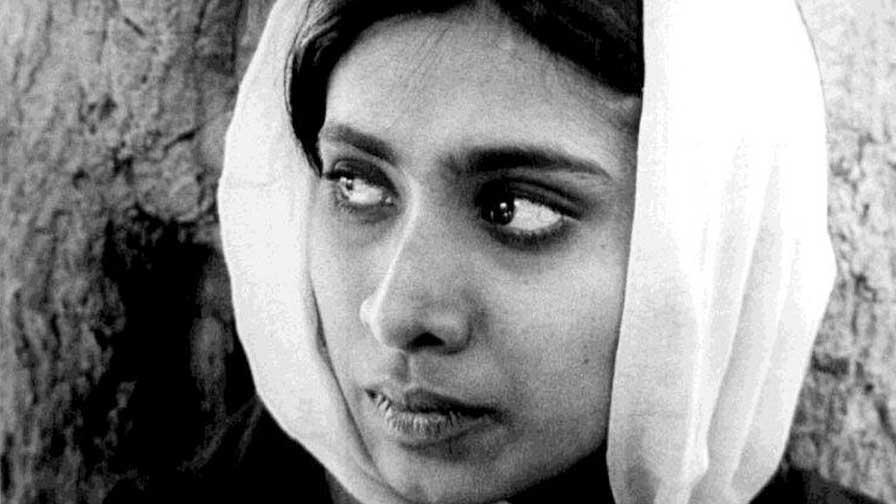

Born in Jodhpur with the name of Ravindra Nath Kaul, he got his nickname of Mani from his family who had a later distaste of the regular Bengali derivative of Robin. Ravindra Nath fell by the wayside and Mani prospered.

Mani completed his graduation from Jodhpur University and then sought admission into the film direction course at the Film Institute of India, Pune as it was then known. Mani was also influenced with the fame and glory achieved by his uncle Mahesh Kaul, who was a well-known film director of the 1940s and early 1950s. There were already at this time a string of senior Kashmiri Pandits who had been working in the film studios of Mumbai with the leading stars, namely, Prem Adib, Jeevan Dar, Ulhas Kaul, Chandramohan Watal and the only woman comedienne, Yashodhra Kathju, to inspire the younger generation of talent from Kashmiri families.

At the film institute, however, under the guidance of his mentor, Ritwik Ghatak, Mani Kaul found the film library of the Institute fairly well stocked with the recent films from France and Germany, which were labeled under the heading of New Wave Cinema. Film literature, referred to as Cahiers de Cinema, also provided explanations to the products from Europe that went contrary to the style of the story narrative from Hollywood.

Mani Kaul’s diploma film ‘Yatrik’ pointed to the kind of cinema that Mani Kaul would contemplate. He received intellectual support from his film institute teachers like Jagat Murari and Ghatak and from his colleagues like Sayyiad Mirza, KK Mahajan, and Shatrughan Sinha.

Launching Mani Kaul into the realm of feature film production proved to be more difficult. No financier was willing to underwrite the young man and his experimental cinema. Finally it was left to the Chairman, B.K. Karanjia of the Film Finance Corporation, who risked the public funds, and based on the recommendations of the teachers of the film institute, offered the funds that finally helped Mani Kaul to begin work on his first film.

This film, which we remember today as ‘Uski Roti’, left its viewers confused, but the film students raved on its styling. ‘Uski Roti’ brought Mani Kaul his first film award from the votes of film critics. It won acclaim as a breadth of fresh wind blowing from India at various international film festivals and BK Karanjia could fend off his critics in the government that his decision to fund Mani Kaul’s project was well grounded.

Mani Kaul’s fellow traveler, Kumar Shahani, shared the same passion for wrecking conventional forms of film narrative. But Mani finally overtook Shahani in his productivity of alternate cinema. It was his belief that cinema only required movements by humans over a landscape and that there should be minimum use of words. Rabindranath Tagore had also made a mention of the same sentiment when in the 1930s he had stated that ideal cinema was one that spoke without words.

Most of the films made by Mani Kaul narrated their stories in as close as real time as possible. In the first public screening of ‘Uski Roti’, the married woman is seen waiting for her truck driver husband to appear, to take his packed meal of two rotis and cooked vegetable. The scene is without music, in open sound and without much stirring of the figure sitting by the roadside. Nearly eight minutes passed before the figure moved and when this happened there was a round of derisive clapping. What the audience missed in its viewing was the loneliness experienced by the wife in the dark of the night, waiting for her husband to appear. It was a real time cinematic experience and the audience was not used to this suggestion.

With Uski Roti, Mani Kaul was also later said to be a harbinger of the rights of the portrayal of women in cinema, though perhaps he may never have visualized this compliment for himself.

Mani Kaul made in all 23 films, both feature and short films. Today he is best known for four works, Uski Roti, Duvidha, Asaad Ka Ek Din, Dhrupad and Siddheshwari. The first three mentioned are feature films while Siddheshwari is a feature length biopic documentary. Dhrupad is a research based topical on classical Indian music.

Mani Kaul shunned the use of popular artists from the commercial Hindi film industry, but when the best-known faces of Hindi screen wanted Mani to use them gratis, he found roles for Shekhar Kapoor in his film ‘Nazar’, and for Shah Rukh Khan in his film ‘The Idiot’. The two actors do not ever speak publicly of their Mani Kaul films, but deep down in their artistic careers both the artists will state proudly their association with Mani Kaul.

This also explains why Mani Kaul is such an invisible man in Indian Cinema and so well known abroad. Primarily, we must fault ourselves to identify our best artists, because the audiences are overfed with the dazzle of colour, fast action, songs and dances and the whole artificial environment painted on the cinema screen that we totally miss the grinding reality of our ordinary lives. It is left to artists like Mani Kaul to point their camera lens to this reality that we shun because it is so real. In the feature length well researched documentary film ‘Dhrupad’ the final sequence runs for a good six minutes when a rendition of Dhrupad is on, while the camera takes a long slow sweep of the Dharavi slum lived by a few lakh poor. The eloquent and the harsh both merge as the frame dissolves into total darkness.

Mani Kaul lived frugally. His films brought him no financial windfalls. Invited to foreign Universities to lecture on the forms of cinema, he used the opportunity to showcase his films to illustrate his narratives.

At home in the early 1990s, Mani was forced to accept a teaching offer in his alma mater, the Film and Television Institute at Pune, where he did not lack a keen audience. This sabbatical helped Mani to keep his body and soul intact and pull himself from the brink of depression, but after creating a new generation of film makers including the now well-known Gurinder Singh, Mani was still without money and acclaim.

It did not help Mani Kaul to know that the Central Government had given him open assurances that it would get his films on the national channel. That promise remained unfulfilled. Mani also briefly shifted base to live in Rotterdam when he found poverty threatening his family. He worked as a resident film advisor on the Rotterdam Film Foundation. At the end of his tenure, he returned to settle down in Delhi where he could keep out the expensive and rotten world at bay.

Today Mani Kaul is more openly talked about in the country. He is linked with the founding of the New Wave Cinema, an alternate style of movie making that kept out colourful studio sets, an 100 piece orchestra on the sound track, buxom girls dancing in the background, and linear narrative. But the tragedy remains that his films are all out of sight. Any announcement of a screening still keeps the audiences away. He thus remains a prophet unwanted in his own land.

It was in 2010 that Mani Kaul was afflicted with an incurable disease. He was with his sons and daughters, settled in life, and a film script based on the illicit romance of the Italian film maker Roberto Rossellini with a married Indian woman. It would have been a departure for Mani Kaul to step on the border of commercial film making. Happily, life itself intervened to keep him steady in his pure form of classicism.

Mani Kaul passed away on July 6, 2011, aged 66, mourned by very few in the country of his origin. Some may now want a memorial to be erected for him. Others may not even worry on this idea. After all the question will remain: Mani Kaul Kaun Tha?

Author’s note:

It was necessary to write on Mani Kaul, no relative of mine, because of his relevance to Indian cinema. The reader is unlikely to come across his works, but if the accident happens, perhaps this introduction will help. This piece was commissioned and read by All India Radio (AIR) External Services in 2016.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.