The intense feeling of longing that we call nostalgia puts us in a homely, familiar space, where we tend to feel safe and secure. Nostalgia always elicits happy, positive feelings. Often, festivals bring with them a wave of nostalgia. The Durga Puja, owing to its cultural, traditional, and personal importance in the lives of the Bengali people, has garnered an unsurmountable nostalgic value. The enchanting atmosphere of the Durga Puja season is second to none. Brimming with the smells of the shiuli (coral jasmine) flower, camphor and incense, and the sounds of the dhak (traditional percussion instrument played during Hindu festivals), kashor (cymbal-like instrument) and ghonta (traditional hand-held bell), the air becomes sentient. It comes to life with music. As the aforementioned elements are considered as signifiers of the Durga Puja, the festival itself is considered by many to be the indisputable signifier of the Bengali people — bringing together people of different communities into a space of euphoric nostalgia. In Sujoy Ghosh’s Kahaani (2012), however, these signifiers are changed in their formal essence, and they, along with several other aspects turn a familiar, homely space into something unfamiliar.

Kolkata is famous for its captivating Durga Puja celebrations, attracting thousands of tourists from other parts of India and abroad. But the welcoming, vibrant Kolkata of the Durga Puja season turns into a hostile space in Kahaani; it turns into a macrocosm of the forbidding suburban lanes that shelter unknown threats and conspiracies.

The overarching symbolic themes of the Durga Puja, such as the celebration of the feminine power, and the war between good and evil, for instance, align with some of the themes of the film. Additionally, the film, through its form, uses the festival for something more than just a plot device, turning it into a narrative device instead. Of course, the conflict in such a backdrop has to be resolved within the timespan of the festivities for achieving closure, but the narrative becomes more engaging through the film’s depiction of the city. Unlike the popular depiction of Kolkata during Durga Puja — enthused with bright colours, smiling faces, and happy melodies — the film presents the city in a different aesthetic. An unsaturated, cold colour palette is used. This gives the city a murky look.

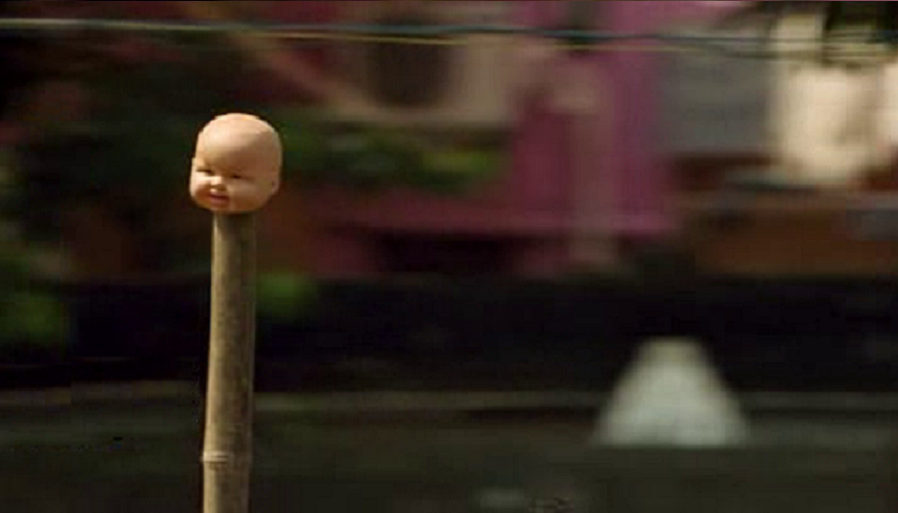

The film contains very few wide shots, making us feel trapped along with the characters. The unstable, shaky aesthetics of the hand-held camera make every moment feel precarious. A particularly different effect is achieved through this in the Bengali audience, more specifically the Bengali people of West Bengal. Through his composition choices, the filmmaker depicts an uncanny version of the Durga-Puja-season-Kolkata in Kahaani. The term “uncanny” is used in psychology to refer to something that seems both familiar and strange at the same time. Encountering the uncanny elicits fear and dread, or at the very least, it puts one in a state of utter mental distress. This uncanniness of the city in Kahaani is bound to make the general Bengali viewer uncomfortable, because it becomes difficult to identify the spaces shown in the film with the mental images that have been preserved for a long time in the collective consciousness of the Bengali people.

The billboards in the city during the puja season fill the people with a kind of joyous anticipation. When I was younger, I used to feel the first thrills of the imminent puja with the arrival of the Anandamela Pujabarshiki (a popular children’s magazine). This would always be followed by the puja-special sales advertisements on the billboards throughout the city. Once I would see the framework of the pandals being made, the countdown would begin. These have always been my personal signals for the season’s arrival. Kahaani employs these same visual cues to establish the time of the year. In the sequence where the protagonist Vidya Bagchi travels from the airport to the police station in a taxi, we see fleeting shots of a billboard, a few pandals and pandal workers, and also the frameworks of some Kali idols. These visuals are recorded through the moving taxi’s window in the style of point-of-view shots, so that the audience gets to share Vidya’s subjectivity. But for someone who has been in the city at this time of the year, these shots feel as homely as they could get.

Presented using what Eisenstein called rhythmic montage, each shot of this sequence matches the beats of the song “Tere Bina Jiya Jaye Na” playing in the taxi’s radio. This song from the 80s reinforces the feeling of nostalgia, and is one of the instances of the director’s cinematic use of sound. The song merges with the surroundings inside and outside the taxi, and mixes with the other dietetic sounds, like the noise of the busy road. The resultant sound takes the form of some kind of an atmospheric background music that seeks to pull memories out of the past. Personally, my memories connected with that particular song were stored in some remote, inaccessible corner of my subconscious. Hearing it at that moment, I pictured my father playing his audio cassettes in the evening when he came back from work. He would play one cassette in the tape recorder, while winding another with a pen, and the whirring sounds of the tape would run in sync with the song. I must have been just two or three years old at the time.

Another instance of the film score consciously or subconsciously addressing the Bengali audience can be found in the scene where a Tagore song “Jodi Tor Daak Shune Keu Na Ashe” plays in the background as Vidya looks at a Durga idol’s arrival procession through a window. The camera captures the procession through the window grates, once again allowing the viewer to share Vidya’s space, while connecting with a Bengali viewer on a more intimate level by making them recollect the memories of gazing out the window and witnessing the arrival of the goddess.

Old Hindi and Bengali songs are used as diegetic sounds throughout Kahaani, setting the tone of the puja season. Songs like “Jete Jete Pothe Holo Deri,” “Amar Shopno Je Shotti Holo Aaj,” “Tu Mera Kya Laage,” “Lekar Hum Deewana Dil,” and “Jani Na Kothay Tumi,” all composed by R.D. Burman, function like ambient sounds, bringing with them waves of nostalgia, but at the same time, alongside the narrative context of the film, they manage to pronounce a foreboding atmosphere.

The cities, towns and villages of West Bengal are adorned with lights during the Durga Puja festivities. Kolkata at this time becomes livelier than ever, but in Kahaani, familiar sights such as the puja crowds and the pandals become alien. They are shown in quick, successive cuts, almost in POV shots, intercut with shots of Vidya wandering amidst the crowd as they stare at her. A pregnant lady walking alone in the streets during a festival becomes an unnatural sight. She looks wary, anxious and lonely, and this seems to grab the attention of the pedestrians. The montage ends with a merging of the diegetic and non-diegetic sounds, as the non-diegetic drumbeats of the background music unites with the diegetic sounds of the dhak being played by the dhakis (dhak-players) in front of a pandal.

The iconic representation of the Durga idol symbolises the victory of good over evil. Similar to Durga stabbing the demon Mahishasura with the pointed end of the trishul (trident), Vidya stabs Damji with her hair bodkin. As she stands over the fatally wounded Damji, she is framed in a low-angle shot. Low-angle shots are typically used to show a character in a position of power or a state of dominance, but this particular one serves an additional purpose. Vidya is seen by the audience in the same way that people see Durga idols in pandals — looking up, from a lower ground level. Placing her at the centre of the frame in shallow focus makes the red bulbs behind her appear like streaks of red, which complement the colours of her red blouse and white saree. Her open locks, her angry (yet composed and resolute) facial expression, and her posture, become a re-enactment of the Durga idol’s iconic representation.

The iconic representation of the Durga idol symbolises the victory of good over evil. Similar to Durga stabbing the demon Mahishasura with the pointed end of the trishul (trident), Vidya stabs Damji with her hair bodkin. As she stands over the fatally wounded Damji, she is framed in a low-angle shot. Low-angle shots are typically used to show a character in a position of power or a state of dominance, but this particular one serves an additional purpose. Vidya is seen by the audience in the same way that people see Durga idols in pandals — looking up, from a lower ground level. Placing her at the centre of the frame in shallow focus makes the red bulbs behind her appear like streaks of red, which complement the colours of her red blouse and white saree. Her open locks, her angry (yet composed and resolute) facial expression, and her posture, become a re-enactment of the Durga idol’s iconic representation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.