Cinema has come a long way from a time when long dialogues struck gold at the box-office and cemented a struggling protagonist’s position as a dependable hero to a time when it is cool to be conversational. Alongside, the big screen has ceded much of its audience to the small screen. Clearly, it is not merely a change in the format, but in the preferences as well. Audiences that immerse themselves in, groove to, and work and live out of, the small screen, prefer lines that are short and not necessarily sweet. Professionals, such as Prasoon Joshi who has dabbled in both screen forms, know quite well that the script and parameters, dialogues included, for a Bhaag Milkha Bhaag are necessitated to be radically different than those of a 30 second commercial for a Happy Dent.

Way back in the heydays of multi starrers and family dramas, things were quite different. A dialogue such as ‘Babumoshai, zindagi lambi nahin, badi honi chahiye’ by Rajesh Khanna, the titular character of Anand, summed up his happy-go-lucky personality, and despite dying slowly every day on screen, the actor succeeded in leaving behind a wonderful mantra for life. In Meri Jung, Anil Kapur played a self-made lawyer whose conscience was pricked with a single dialogue. He took up what appeared to be a doomed case when he heard the same words his mother used in her plea to a lawyer to save her innocent husband from the gallows—‘Jiske paas koi saboodh ya gawaah nahin hota, kya vo begunaah nahin hota?’

Way back in the heydays of multi starrers and family dramas, things were quite different. A dialogue such as ‘Babumoshai, zindagi lambi nahin, badi honi chahiye’ by Rajesh Khanna, the titular character of Anand, summed up his happy-go-lucky personality, and despite dying slowly every day on screen, the actor succeeded in leaving behind a wonderful mantra for life. In Meri Jung, Anil Kapur played a self-made lawyer whose conscience was pricked with a single dialogue. He took up what appeared to be a doomed case when he heard the same words his mother used in her plea to a lawyer to save her innocent husband from the gallows—‘Jiske paas koi saboodh ya gawaah nahin hota, kya vo begunaah nahin hota?’

Amitabh Bachchan’s iconic scene at the temple in the Deewar climax is etched in public memory. What made it so? It lent depth, and established layers for the flawed but loved protagonist. It gave space to his angst and emotions, and, to an extent, it justified his questionable and conventional choices. In the same movie, a scene between two brothers on diametrically opposite sides of the virtue scale ended with a dialogue that is still remembered today—‘Mere paas maa hai’. The dialogue emphasized that the virtuous brother, even though he had no material possessions, is the richer of the two because he had his mother on his side. In Trishul, when the angst-ridden protagonist proclaimed, ‘Aaj meri jeb me phoonti kaudi nahin hai aur main paach laakh ka sauda karne aaya hoon’, it highlighted his confidence. And in the climax, it lent expression to his grief when he threw the dialogue, ‘Maine aap jitna gareeb insaan nahin dekha’ to his biological father who had left his mother for wealth. ‘Mazdoor ka paseena sookhne se pehle use apni mazdoori mil jaani chahiye’, in Coolie, made it clear that a labourer shouldn’t be made to wait for the fruits of his labour. Khuda Gawah had Amitabh Bachchan mouthing a long dialogue in praise of love and how it triumphs over everything else.

Dialogues such as ‘Na talvaar ki dhar se, na goliyon ki bouchaar se, bandaa darta hai to bas Parvar Digaar Se’ were used as a technique to introduce a central character or the ideology that they practised. Hollywood’s superhero Spiderman too had one to explain his—‘With great power, comes great responsibility’. Some dialogues evoked warmth of bonds and togetherness, or the reverse—‘Yeh to tune theek hi kaha… ki mar gaya raju aur khatm ho gaya veeru’ from Saudagar marked the moment of rift between two lifelong friends.

Unlike in the olden days when dialogues were considered relevant, the advice of today’s industry folks to ‘keep it short’ or ‘cut it short’ seems to be a short cut, templatised approach to hook audiences who may find long dialogues to be too dramatic and unreal. For the audiences of today, dialogues don’t seem to be the tool to build a character; subtle mannerisms and actions seem to be the preference. We often talk of low-attention span, but does this not point at the writer’s failure to be able to hold the audience’s attention? Social media is full of timelines that reflect great love for smart and inspiring one-liners. Several youngsters wear t-shirts sporting smart one-liners to reflect their attitude and swag. Smart videos and memes seem to be forwarded in huge numbers. Perhaps, the wit of words works better on personalized platforms instead of the cinema screens. The fact remains, though, that powerful lines still leave the audiences spellbound. Even at the time when chocolate heroes were replacing the angry young man, the long dialogue by Amitabh Bachchan in Baghbaan, released in the early 2000s, succeeded in striking a chord with the audiences.

What is it about dialogues that endear themselves to audiences? Is it mere wordplay? Are dialogues like closed curtains, using which we can get to know a personality better? Do dialogues have to be merely instructional or can they stand out as life mantras? The popularity of dialogues reflects the power of words in creating an impact on minds and hearts. What songs and dance are for expressions, dialogues are for the story. The inherent risk in keeping cinema stark real is that it can appear to be an isolated episode and not an integrated construct. Dialogues also reflect the fact that the character has a very good understanding of their life or their situations or their principles.

What is it about dialogues that endear themselves to audiences? Is it mere wordplay? Are dialogues like closed curtains, using which we can get to know a personality better? Do dialogues have to be merely instructional or can they stand out as life mantras? The popularity of dialogues reflects the power of words in creating an impact on minds and hearts. What songs and dance are for expressions, dialogues are for the story. The inherent risk in keeping cinema stark real is that it can appear to be an isolated episode and not an integrated construct. Dialogues also reflect the fact that the character has a very good understanding of their life or their situations or their principles.

Dialogues lend depth to the underdogs’ persona. It allows them a way to vent their angst and express their sorrow. They bear the burden of explaining their position, choices, and unfulfilled wishes to the audience. Dialogues rescue the underdog. The armor of words overrides the underdogs’ humble abode and modest clothing, and elevates them to the pedestal of the favoured victor. Often, in a vulnerable on-screen moment, it is a dialogue that helps the protagonist swing from being a subject of lament to a subject of pride and inspiration. Finely-framed dialogues rivet audiences to their seats by swinging the pendulum of power between the protagonist and the antagonist, who could be anything from a character to a situation, an illness, or a loan deadline.

Dialogues that are criticized for being preachy may well be the mantra of inspiration for struggling individuals. And when aided by a well-integrated construct of all the other elements, including visual cues, story, and aesthetics, dialogues add depth to the film, which is why, in filmmaking courses, dialogues are an important chapter of study. The movies of today may rely more on conversational tones, but perhaps the drama will not emerge so powerfully without strong dialogues. This leads to the questions—In our bid to appeal to the smartphone generation, should long, dramatic dialogues no longer be considered in storytelling? And will long, dramatic dialogues in films someday eventually cease to be a primary element?

[divider size=”1″ margin=”0″]

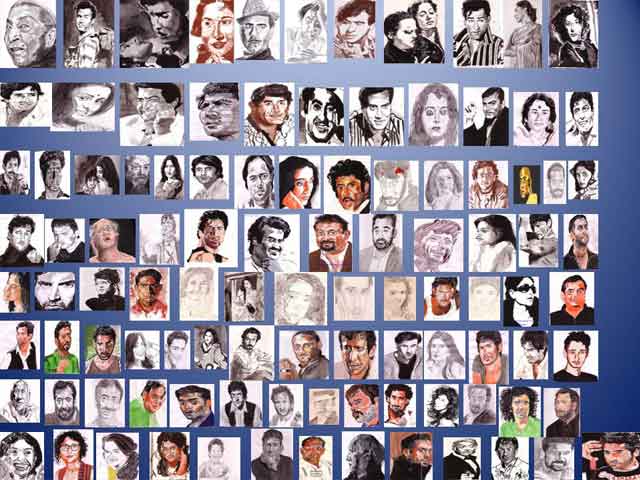

The artworks are by the author himself. He has done well over 350 portraits of film stars from the early to the present eras.

A very well written and a well researched article. Hope it will be included in textbooks or courses of film making as a chapter.

Dialogues are important to tell or enjoy a story. But we are not talking about radio play, there are non-verbal expressions too in cinema. Added to that there are use of symbolism and mood enhancing music or environments embellished with cinematic lighting and interplay of camera and subject movements, angles and positions….and not to undermine the dramatic structure and handling of time. Also we know how a popular actor is received, for example Kesto Mukharjee.

Good work, keep going strong