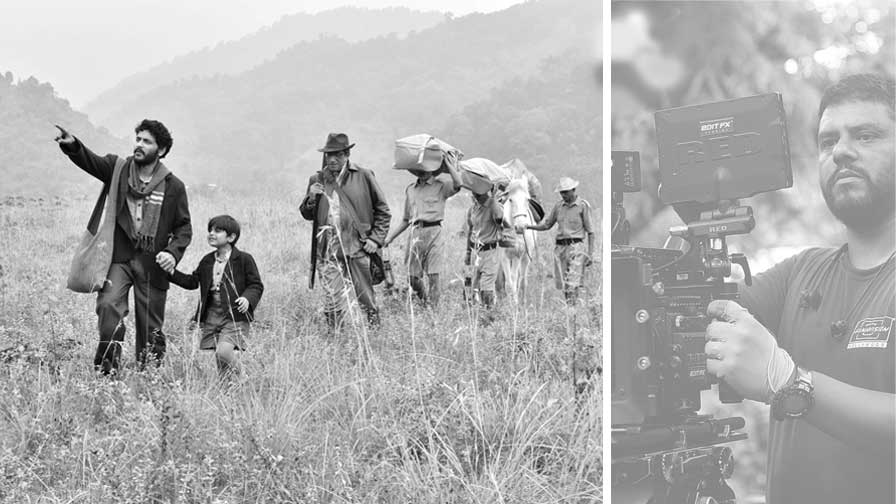

Utpal Datta converses with Supratim Bhol, the cinematographer of Avijatrik, lit., the wanderlust of Apu, purportedly the concluding part of Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy based on the remaining portions of the novel Aparajito by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay.

A film is a sort of a dream, a combination of imaginary images in the mind of the director. The job of the DoP is to convert those images into reality. What degree of understanding is essential between the two people?

A writer and a director lives for a long period with their script. They live, eat, drink and sleep with it. They generate a certain series of images through living with it, and ultimately they wish to bring these images that have been formed in their mind onto the screen. Supratim Bhol

As a DoP, the one thought that runs through me is this — how can I contribute to those series of images and bring out a more enriched product? I would always want to increase the production value of the film through my understanding of aesthetics. Discussions happen over months, sometimes years, as to how to proceed towards executing them. Eventually, the DoP becomes an eye of the director, and keeps on adding elements that enhance the whole film. Often times, alterations, modifications and adjustments are required to be made at the final moment too — at the time of the execution of the scenes.

The better communicated and evolved the Director and DoP are the more perfectly matched their piece of art turns out to be. Supratim Bhol

To bring alive a film, what does the cinematographer require from members of the various other departments?

Synchronization. Everyone involved in the production, irrespective of their department and individual duty, must be on the same page. Since all are involved in making one and the same film, the motto must be “many in body and one in mind.”

A director is a creative individual, and so is the DoP. A director has a special individualistic type of creation, and so has the DoP. How then, as a DoP, do you work with a variety of directors each of whom has a different thought process, and still maintain your own signature?

We are all human beings. And we all possess a different philosophy. The philosophy in us has grown out of our life, our childhood, our mental nourishment, our upbringing. The books that we have read. The places we have travelled. The luxuries and hardships we have experienced. The people we have met, accepted and rejected. The situations we have faced; and moved out of, or not. And the wins and losses that have come our way. So, in general, we are all creative in certain ways and have evolved through our personal journeys.

However, when one artist collaborates with another on a professional job their primary responsibility is towards the art that they have been assigned to create together. When a DoP with full technical responsibility and a director commit to a script, therefore, though there is bound to be differences in the way they each think and ideate, they should both strive to be in harmony. The two of them as well as the entire team should become one. Because all would be creating just one film, all should come together as one team out to achieve that singular goal.

Individually, every artist has their own strong and weak points. And an artist who is wise will rely on their strong points to stamp their signature on whatever they do. Traces of our own taste of aesthetics will always keep our signatures intact.

Thematically, Avijatrik is a continuation of Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy. Did the pressure of shooting for the sequel of such a timeless classic get to you?

Avijatrik essentially means one who is forever on a journey. The journey may be an eternal one, or it may be one that is adventurous and fraught with challenges and hardships. The shooting of Avijatrik was no different. Right from the very moment when the director, Subhrajit Mitra, was convinced that he wanted me as the DoP, we both knew that there would always be an added pressure on us.

However, I had cultivated a certain sanctity for the would-be film. My spirits were really high and indomitable. So, even though the pressure was high, it never touched me. I treated this film as an individual film, and packed my bags accordingly. I had never planned to shoot it out of the way or different. Of course, I tried to retain my individuality while being in harmony with the trilogy. Now that the film is made and ready for the festival circuit, it is totally up to the audiences and jury to assess what has been captured.

What were the challenges you faced well before rolling camera? Supratim Bhol

Every film has its challenges. The primary one of Avijatrik was to recreate the 1940s world of Apu. Almost sixty years have passed since the last of the trilogy was shot. The whole world has changed. There are hardly any traces of the pre-independence era in our daily surroundings. Finding such locations — houses, roads, lanes, alleys — was quite a task. Supratim Bhol

Furthermore, Apu /Apurbo is an iconic character in the minds of the Bengali audience. He is a dreamer, a writer, a wanderer. Building the world of Apu, and evolving through craft to make the audience believe in the Apu was a humongous task. Shooting the film in black and white, the process of giving a seamless effect of the VFX within the live action shots, setting up the locales, getting involved in the research — everything was a huge challenge given that we were shooting a period film with very limited resources. The entire film was planned to be shot in 22 days across 70 locations in and around northern and eastern India. It was made possible only because all the departments put in their greatest efforts.

You shot in the same black-and-white tone as the original trilogy, but chose a wider format. What was the reason and logic behind this decision?

The aspect ratio is definitely an important part of storytelling. I have chosen the 16:9 format to incorporate and thereby showcase more information with a wider view. If the 16:9 format was available in the 50s, most filmmakers would quite likely have preferred it.

The visual design of Sahaj Pather Goppo is a juxtaposition of two opposing styles — in the opening and closing sequences the camera moves a lot, whereas in the rest of the film the shots are mostly static. From an aesthetic point of view, does such a contrast fit into the narrative?

I always follow my instincts about shot taking. While reading the script, the sequence grows in me in a certain way and I decide the shot movement accordingly. It’s an amalgamation of my feelings and the director’s vision, I believe.

The rain sequences are realistic, but I understand they weren’t shot naturally?

Yes, since the entire film is set in the monsoon time, we decided to shoot in the rainy season but using a rain machine too. Monsoon Bengal is very beautiful. And children being integral part of the film adds to the beauty. But shooting in the rains is hectic. There is mud and water all over. At times it can quite frustrating too. Thankfully, the zeal to create good visuals is often rewarded with a positive result. I chose to not use any separate light to highlight the rain in order to give the rain an organic look. The colorist too has done well in maintaining that feel.

How touchy are you about your visuals being manipulated in post?

Sometimes, it becomes highly necessitated, especially if one is shooting with restricted resources. For instance, in Chorabali, a complicated thriller with several layers, the director wanted a Hollywood look. So, the visual design was generated through lighting and grading in post production.

How would you rate your own work? Supratim Bhol

Well, I restrain myself from wearing the hat of a critic. I don’t think I would ever be able to rate the cinematography, or any other department for that matter, of my or any other film. For, I know well that each film has its own challenges, and everyone involved usually attempts to put in their best efforts and showcase their skills to the fullest.

I could however tell you my view of what makes for great cinematography. It happens when the imagery blends smoothly with the story and the action, and does not stand out on its own. There can be nothing more beautiful than this to celebrate the art of cinema.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.