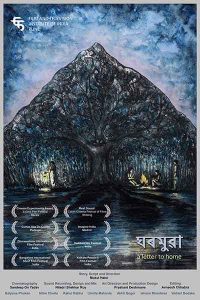

Film: Ghormua

Director: Mukul Haloi

Duration: 25 mins

Language: Assamese

Award: Winner of the Cinema Experimenta Award at SiGNS

Gilles Deleuze defines a crystalline-image as that image in which the transparent actual image and the opaque virtual image simultaneously exist. For Deleuze, when Scottie in Alfred Hithcock’s Vertigo makes Judy into Madeleine he has juxtaposed the actual with the virtual. The juxtaposition of actual and virtual creates a crystal-image, which for Deleuze underlines the material specificity unique to the cinematographic idiom.

In Mukul Haloi’s diploma film Ghormua, this crystalline-image of time is presented as a kind of writing, which his characters free up by recitation.The film begins with a shot of an old lady operating a piece of equipment. This Heideggerean discourse around equipment as a tool to arrive at Being-there (Dasein) enters the denotational or symbolic regime. This symbolic regime is represented on the image track by the characters’ sleeping, waking and dreaming.

In Mukul Haloi’s diploma film Ghormua, this crystalline-image of time is presented as a kind of writing, which his characters free up by recitation.The film begins with a shot of an old lady operating a piece of equipment. This Heideggerean discourse around equipment as a tool to arrive at Being-there (Dasein) enters the denotational or symbolic regime. This symbolic regime is represented on the image track by the characters’ sleeping, waking and dreaming.

On the other hand, the sound provides us with the reality of the image (outside the domain of intentionality). As in Godard, (at the beginning of the film) the inside of the frame points to the outside. Simultaneously, the deep focus points to what is before or beyond the denoted image. The characters are all written in time, whilst the shot of the road covered with crouching trees is Ozu’s “little time in its pure state”, at different degrees of intensity determined by the presence or absence of light.

The symbolic (denotational) regime enters the indexical regime through the shot of the character Rahul taking a photograph i.e. constructing memory. In other words, creating memory is part of the mise-en-scene of the film. Dreaming, sleep and waking are part of the denotational image as they are represented through the order words of language. The camera is placed at a distance so that the recording of the image deconstructs its own construction. The sound of the bird, that possibility for grace, becomes an index for its own line of flight, at which point the deep focus is disrupted. This is followed with the low angle tracking shots of trees interspersed with smoke: an index for fire. When the fire is eventually indicated on the image track, Ghormua returns to the symbolic regime from the indexical regime. Consequently, the sound of fire frees the construct through its own reality i.e. it is the assemblage’s line of flight. This produces a Self, that is mirror-reflected in the manifest world (as in the films of Tarkovsky), just as the characters and objects are reflected in the lake. And doesn’t cinema only provide us with this manifest reality with higher dimensions of realism without showing us the Absolute?

The symbolic (denotational) regime enters the indexical regime through the shot of the character Rahul taking a photograph i.e. constructing memory. In other words, creating memory is part of the mise-en-scene of the film. Dreaming, sleep and waking are part of the denotational image as they are represented through the order words of language. The camera is placed at a distance so that the recording of the image deconstructs its own construction. The sound of the bird, that possibility for grace, becomes an index for its own line of flight, at which point the deep focus is disrupted. This is followed with the low angle tracking shots of trees interspersed with smoke: an index for fire. When the fire is eventually indicated on the image track, Ghormua returns to the symbolic regime from the indexical regime. Consequently, the sound of fire frees the construct through its own reality i.e. it is the assemblage’s line of flight. This produces a Self, that is mirror-reflected in the manifest world (as in the films of Tarkovsky), just as the characters and objects are reflected in the lake. And doesn’t cinema only provide us with this manifest reality with higher dimensions of realism without showing us the Absolute?

Haloi is inculcating the power of repetition in the image that is simultaneously dreaming, awake and in a state of perpetual deja vu. This power of repetition creates rhythm in the indexical regime, finding its culmination in the theatricality of the performance, by the character who evokes the beloved. The transformation of the object in the film  is precisely this transformation from material equipment (as in the opening sequence) to immaterial equipment represented through MacLuhan’s “massage” i.e. the medium. The utterances are indexes of writing, much like cinematography, in Robert Bresson’s sense, is a writing with movement and sounds. This indexical regime finds its counterpoint in the intensity of light. This intensity of light is gradually diminished until the shot of the completely dark room that shows us the lamp as light source. This symbol of lamp as light source takes us back into Plato’s cave of shadows connected through that physiological aspect of film: the cut.

is precisely this transformation from material equipment (as in the opening sequence) to immaterial equipment represented through MacLuhan’s “massage” i.e. the medium. The utterances are indexes of writing, much like cinematography, in Robert Bresson’s sense, is a writing with movement and sounds. This indexical regime finds its counterpoint in the intensity of light. This intensity of light is gradually diminished until the shot of the completely dark room that shows us the lamp as light source. This symbol of lamp as light source takes us back into Plato’s cave of shadows connected through that physiological aspect of film: the cut.

In Haloi’s film, the dream consciousness requires the mediation of language which moves from the indexical regime to that of suggestion. This suggestive discourse has an absence of light: that zero-intensity Body without Organs; that creates an imaginary image which the spectator realises by listening to the utterances on the soundtrack. The character, looking outside the frame, describes her dream; as the framing shows us the hands of a character outside the frame i.e the inside points to the outside and vice-versa (is this an indication of Godard meeting Bresson? A strange proposition!). In the meanwhile the sound points to the reality of the image, which for Haloi is the horizontal movement of the final shot: the flattening out of the image to a single dimension.

[divider top=”yes” anchor=”#” style=”default” divider_color=”#999999″ link_color=”#999999″ size=”2″ margin=”0″]

The director of Ghormua, Mukul Haloi, studied filmmaking at FTII. His documentary ‘Tales from our childhood’ is included in the film course at Gottingen University, Germany. He has been a special invitee at Griffith Film School, Australia, as well as Berlinale Talents, Germany.

Ghormua is presently streaming on Movie Saints. And below is the screener of one of his earlier short films.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.