“I have never been to a cinema. But even to an outsider, the evil that it has done and is doing is patent. The good, if it has done any at all, remains to be proved.”

“If I Was Made Prime Minister… I Would Close All the Cinemas and Theatres.”

“If I had my way, I would see to it that all the cinemas and theatres in India were converted into spinning halls and factories for handicrafts of all kinds. What obscene photographs of actors and actresses are displayed in the newspapers by way of advertisement! Moreover, who are these actors and actresses if not our own brothers and sisters? We waste our money and ruin our culture at the same time.”

Truth to tell, the Mahatma has not been far off the mark in his opinion, especially in the pandemic hit Covid-19 dictated “social distancing,” “quarantine” driven masked milieu. Profound passages from several of the writings of the Mahatma (Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi) in various journals and speeches eloquently and evocatively convey the abject abhorrence of the Idea of Cinema from the self-confessed and implicitly-held Father of the Nation’s ‘puritanical’ and ‘catholic’ perspective.

In these troubled times, streaming works over OTT platforms has been the order of the day. Distributors are required not only to beat the Censorship blues but also to dish out all kinds of vitiating and corruptive content to cash in on the people’s need to be “engaged.” All in the excuse of providing uninterrupted ubiquitous “entertainment” to battle “ennui” and “claustrophobia” while being cocooned in the safety net of one’s homes, keeping Corona at bay.

Cinema, since he strode on this earth and eventually departed felled by an assassin’s bullet, even before the Mahatma could experience the Free India he had fought and laid down his life for, may have coveted the hallowed persona of Mahatma Gandhi to propound his philosophy and the enigma he was as a person. Yet, Mahatma Gandhi, the Father of the Nation, may have been the subject of many a movie that has graced the Indian celluloid screens, from time immemorial.

Filmmakers have left no stone unturned to depict, and bring to life, the Apostle of Peace and his philosophy of non-violence as a potent weapon of civil disobedience against the State. [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]While film makers may per se not have ingrained Gandhian thoughts or philosophies themselves, the Mahatma’s influence on cinema has been pervasive.[/highlight]

The father figure, however, has been a tall, towering moral force, with movie makers perpetuating his principles and teachings in film after films, the great soul being an eternal fount of inspiration for the entire galaxy of filmmakers.

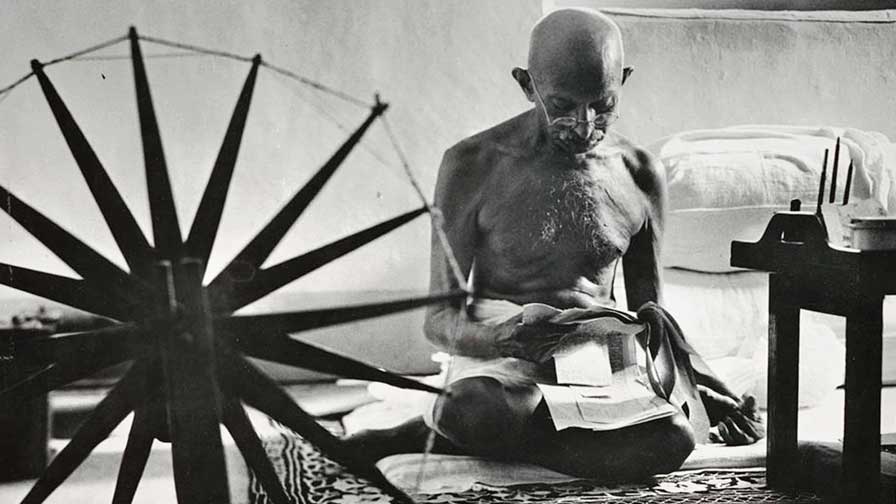

From newsreels and documentaries to feature films, Gandhiji has been a fixture. It is through them that we find our Gandhi with that rounded spectacles, an ever-smiling benign face, the chained waist watch, clad in a loin cloth and the patent furious gait with baton, the picture of him and his mannerisms, as seen on screen, in cinema.

Every October 2nd we celebrate his birthday in all forms of media entertainment platforms. We lose no moment in bringing to our living rooms some visual image of the Mahatma trying to perpetuate his “long forgotten’ ideals among the audiences – young and old, across all ages and avocations.

So much so, ironical though it may seem, in a lucid testament to his popularity in mankind’s every day discourse, you have his wax statue at Madame Tussauds sharing the limelight with other personalities drawn from the world of cinema. This testifies to being antithetical to his own held beliefs about films and its harmful and debilitating effects on the psyche and life of man.

It is no wonder then that late Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, way back as early as 1963, had a word of cautionary advice to Richard Attenborough, when the latter had sought Nehru’s nod for a biopic on the Mahatma, and who in 1982, a good two decades later, eventually went on to make Gandhi.

Pandit Nehru wisely counselled Sir Attenborough thus: “Whatever you do, do not deify him – that is what we have done in India – and he was too great a man to be deified”. Gandhi “had all the frailties, all the shortcomings. Give us that. That’s the measure, the greatness of a man.”

Trust film makers to heed to such sane, wise words. [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]Such was the deification and elevation of Mahatma Gandhi to the exalted realms of “purity” and “divinity personified” that, even in his lifetime, no filmmaker or literary figure had the temerity to cast aspersions on Mahatma’s ideals, or the sagacity to evaluate his life, principles and beliefs objectively.[/highlight] Even Gandhiji’s rather fructuous filial relationships, be it with his father, wife, brothers, or sons, were always veered around to his stated belief or point, unlike his other political contemporaries who were put under the scanner.

Hindi cinema has used Gandhi’s name to sell its wares, even during Mahatma Gandhi’s lifetime. Such was Gandhi’s popularity in the 1930s and 1940s that many film hoardings would put life-size pictures of him over the photographs of heroes and heroines. So much so, after his assassination, a good plentiful of songs were composed to sing paeans on the ideals of truth and non-violence and venerate and celebrate Gandhi’s contribution to India’s freedom struggle.

Film poster of Mahatma Gandhi: 20th Century Prophet

From Mahatma Gandhi: 20th Century Prophet, a 1953 American documentary film written by Quentin Reynolds and directed by Stanley Neal and Mahatma: Life of Gandhi, 1869–1948, a 1968 documentary produced by The Gandhi National Memorial Fund in cooperation with Films Division, and written-directed by Vithalbhai Jhaveri to The Making of the Mahatma, a 1996 joint Indian-South African film by renowned filmmaker Shyam Benegal based on The Apprenticeship of a Mahatma by Fatima Meer, there has been no dearth of docu-features.

Biopics and full length fictional films on the Mahatma include Feroz Abbas Khan’s Gandhi My Father, Rajkumar Hirani’s Munna Bhai franchise, Karim Traïdia and Pankaj Sehgal’s The Gandhi Murder, and A. Balakrishnan’s Welcome Back Gandhi (Mudhalvar Mahatma). Actor-director Kamal Haasan who made Hey Ram says, “I had a controversial opinion of Gandhi when I was a teenager. This film is my apology to him. I never called him Mahatma because I wanted to see his face for what it was before such a big halo.”

Art house auteurs too were part of this Gandhi mania. In Kurmavatara, Kannada auteur Girish Kasarvalli showcased how the Gandhi name has been appropriated by all and sundry. His understudy, P Seshadri came up with an abjectly poor pastiche of a film detailing Mahatma as young Mohandas in the eponymous film Mohandasa. And you had Assamese film maker Jahnu Barua board the Bollywood bandwagon with Maine Gandhi Ko Nahin Mara hoping to hit paydirt. The spirit of Mahatma has been all invasive and pervasive across all strands and stratosphere of film making.

However, trust the Mahatma himself to have enjoined and ingrained a similar ‘benevolent’ “all embracing goodness of cinema” disposition to the films. Gandhiji failed to see in it a medium that became the opiate of masses to escape from the harsh realities of life, seated in a dark theatres.

Film still: Gandhi My Father

It is indeed ironic that the great savant, who won India her Independence and freed India from the shackles of British Raj, and has been an inspiration to be depicted on celluloid many times over, venerating him, even to this day, took time to watch only few reels of just one movie in his entire lifetime.

Down with illness, Gandhi, aged 74, consented to see select reels of Vijay Bhatt’s Ram Rajya (1943), a film based on Gandhiji’s favourite epic, Ramayana. This was at a special screening at Juhu, in Mumbai on June 2, 1944. He had agreed to watch it for about 40 minutes, but ended up watching it for an hour and a half. The filmmaker later described Gandhiji as being “cheerful” at the end of the show.

Prior to that, Gandhi had been persuaded, unsuccessfully, to watch Mission to Moscow, a Hollywood movie by Michael Kurtiz filmed to promote American alliance with the then USSR. He is believed not to have thought very highly of cinema, for his innate belief and presumption was that Hindi as well as foreign films promoted immorality and corrupted young minds.

Given the kind of films and web series bombarding various OTT platforms today, Gandhiji’s summation on cinema is not far from the truth. [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]Free from constricting demands of Film Certification, film makers have, one may say, gone to the seed, bringing onto mobiles, TV sets, what have you, virtually visual debauchery,[/highlight] to say the least.

It is no wonder then that the Mahatma’s abhorrence of cinema and its ill-effects on mankind was so potent, omniscient, so much so that when a questionnaire was provided to Gandhiji by T Rangachariar, the then Chairman of Cinematograph Committee, in 1937, to elicit Gandhiji’s views on cinema, without an iota of hesitancy, the Father of the Nation described cinema as “sinful technology” and “a waste of resources and time.”

Such was the Mahatma’s poor opinion of cinema that, inimical to the very idea of cinema as a form of entertainment, he once told a panel, “Even if I was so minded, I should be unfit to answer your questionnaire, as I have never been to a cinema. But even to an outsider, the evil that it has done and is doing is patent. The good, if it has done any at all, remains to be proved.”

Never the one to have been enamoured or over awed by the marvel of this magical medium, his antipathy towards movies being so distasteful, in an interview published on May 3, 1942, in The Harijan, the paper he edited, the Mahatma observed, “If I began to organise picketing in respect of them (the evil of cinema), I should lose my caste, my Mahatmaship…! May I say that films are often bad.”

For, he noted, “I have never once been to a cinema. Refuse to be enthused about it. Waste God-given time in spite of pressure sometimes used by kind friends. Its corrupting influence obdurates itself upon me every day.”

[highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]Gandhiji, a vociferous votary and practitioner of celibacy, believed that cinema could break a person’s vow for self-control.[/highlight] “You will avoid theatres and cinemas. Recreation is where you may not dissipate yourself but recreate yourself,” he observed in the preface to his book Self-Restraint vs Self-Indulgence.It is such pithy aphorisms that surface as one delves into Gandhiji’s idea of cinema and its “corruptive influence” on a person’s psyche. Such was the Mahatma’s innate belief that he was not the one to climb down from his stated position despite the pleading of writer-film maker Khwaja Ahmad Abbas to him to look at the positive contribution of cinema to entertainment and its utility as a tool to further the cause of Indian freedom movement.

Such was his steadfast opinion and antipathy towards cinema that he was rather reluctant in meeting up with one of the greatest comedians of the silent era, Charlie Chaplin, whom he simply dismissed as “a buffoon”. The two, though, met on September 22, 1931 during Gandhi’s visit to England for the Round Table Conference.

Such was his steadfast opinion and antipathy towards cinema that he was rather reluctant in meeting up with one of the greatest comedians of the silent era, Charlie Chaplin, whom he simply dismissed as “a buffoon”. The two, though, met on September 22, 1931 during Gandhi’s visit to England for the Round Table Conference.

It is true that during Gandhi’s lifetime, Indian cinema did not quite have the potential to shape the minds of public; that is something it acquired a few decades later, post-Independence. However, post his death, film makers have not been wanting in bringing his life story onto the screen.

Gandhiji wrote in Young India, in 1927, “You will avoid theatres and cinemas. Recreation is where you may not dissipate yourself but recreate yourself. You will, therefore, attend bhajan mandalis where word and tune uplift the soul.”

The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, 1965, provides enough personal viewpoints held by Gandhiji on cinema. In a letter to Helene Haussding, he writes, “I know that overwork and terrific strain are just as apprehensible, even though they may be in a good cause, as a drinking-bout or visiting cinemas. The results of both are the same.”

The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, 1965, provides enough personal viewpoints held by Gandhiji on cinema. In a letter to Helene Haussding, he writes, “I know that overwork and terrific strain are just as apprehensible, even though they may be in a good cause, as a drinking-bout or visiting cinemas. The results of both are the same.”

Addressing labourers in Rangoon in 1929, Gandhiji says, “The cinema, the stage, the race-course, the drink-booth and the opium-den—all are enemies of society that have sprung up under the fostering influence of the present system threaten us on all sides.”

In a letter to Kasturba, in 1934, he expounds: “In Ahmedabad, children get headaches, lose the power of thinking, get fever and die. It is on the decline now. The disease is caused by going to the cinemas.”

And at a prayer meeting in 1947, he says to the gathering, “Why do you need a cinema here? Cinema will only make you spend money. Then you will also learn to gamble and fall into other evil habits.”

But the irony of life and the times in which we live in today is that, [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]come October 2, no efforts are spared to ensure that there is a deluge of film of all hues and making on and about Gandhi as “entertainment,” to remember and pay homage to the “half naked fakir”[/highlight] as Winston Churchill described the Mahatma.

Gandhi may have shunned, and smirked at, film as an avoidable and detestable corruptive beast, but the beast of cinema makes the most of the Mahatma whenever it falls short of ideas; it seeks refuge in his name and fame to champion the man and his message. Then, today and tomorrow. It’s good that his venerable memory is being perpetuated. For, as Albert Einstein once said, “Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a man as this one ever in flesh and blood walked upon this Earth.”