One man, but so many lives! And each life impacted so many personalities… One thought that created history. So many thoughts that continue to impact histories of so many lands…

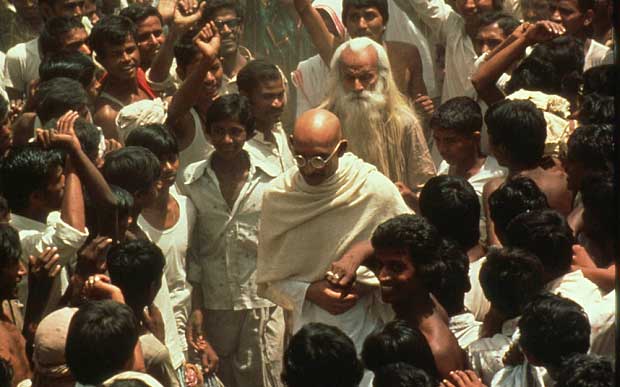

Perhaps that is why any mention of Gandhi makes us think – first and foremost – of Richard Attenborough’s definitive biopic. This 1982 epic on celluloid covers 45 years of Gandhi’s 80-year-life, from 1893 to 1948. It is strewn with abiding images – of Gandhi floating away his chaddar in the river, for a shivering woman to cover herself with; of the dignified grieving when he loses his wife; of his determination as he sets out on the Dandi March and his insistence in not resorting to violence in the face of lathicharge. Most of all it is interesting to see Gandhi, a Hindu, practicing Islam and Christianity as lessons in tolerance.

For a quarter century before he was silenced, this citizen of India had been “the major factor in every consideration of the Indian problem,” Clement Attlee had said on January 30, 1948. The earliest film on Gandhi was made within five years of his passing. It was an American feature documentary, titled Mahatma Gandhi: 20th Century Prophet (1953). Another documentary on his life, made in 1968, had covered all the eight decades of his existence. A much better insight into his life is provided by Shyam Benegal’s The Making of a Mahatma/ Mohan Se Mahatma Tak (1996). Based on Fatima Meer’s book, it focused on Gandhi’s 21 years in South Africa where he tumbled upon the weapon of Satyagraha that he was to wield with enormous success back home in India – and which he willed to the world post 20th century.

However, Mohandas Karamchand of Kathiawad was one life that impacted so many world leaders, defying their colours. So we cannot talk Gandhi without talking of Sardar (1993), Ketan Mehta’s biopic on Vallabh Bhai Patel. Of Jamil Dehlavi’s Jinnah (1998), where Christopher Lee played the founder of Pakistan. Of Netaji – The Forgotten Hero (2005), Shyam Benegal’s epic encapsulation of Subhash Chandra Bose’s struggle for an Azad Hind. Of Babasaheb (2000), based on the life of Ambedkar. Of Lord Mountbatten, captured in Viceroy’s House (2017), Gurinder Chadha’s historical drama. The British-Indian production accounts for the years leading up to the Partition of India under the last Viceroy. Of Bhagat Singh (2002) who inspired Rajkumar Santoshi’s retelling with Ajay Devgan essaying the legend. Of Veer Savarkar (2001), whose life was documented by Ved Rahi with public funding, perhaps the first instance of it. Of, yes, even Adolf Hitler! Dear Friend Hitler (2011), a drama film, was based on letters written by Gandhi to the Nazi Chancellor of Germany during WW2. Have I missed Gurudev? No. In spite of their differences on many socio-political issues, their deeper affinities transcended occasional barriers, Satyajit Ray documented in the centennial portrait of Rabindranath (1961), the ever celebrated bard who gave Gandhi the mantra of Ekla chalo re… Recently – in October 2018 – M K Raina staged a play based on the letters exchanged between Gandhi and Tagore, again showing how greatly they respected each other’s view, even when they diverged. And how can I miss Panditji?! Can there be any film on Nehru without his political father-figure in it? Nor did Shyam Benegal when he mounted the Indo-Soviet coproduction, Nehru (1983).

And just as the sun shines on trees big and small, Bapu made no exception nor relent in his principles for anyone, family, friend or foe. So, talk Kasturba and we talk Gandhi. Talk Harilal, and we talk Gandhi, My Father (2007). Talk Nathuram Godse, and he’s placed in a mock trial in At Five Past Five, made in 1960s. It had started in 1963 with the controversy-rid Nine Hours to Rama, Mark Robson’s adaptation of Stanley Wolpert’s book published in 1962. In Lalit Sahgal’s astoundingly persuasive Hatya Ek Akar Ki, staged once again on January 31 by M K Raina. In Hey Ram! (2000), where Kamal Haasan projects the dilemma of a would-be-assassin who is overtaken by Godse. And the assassination is at the core of The Gandhi Murder, a conspiracy theory film related via three policemen who have learnt Gandhi will be killed. This film released on January 30. What accounts for the fascination with The Assassination? The fact that Godse’s final statement was banned from the public realm for 30 years? Or the fact that the seeker of Ahimsa not only struggled in a landscape of violence but also died by a gun?

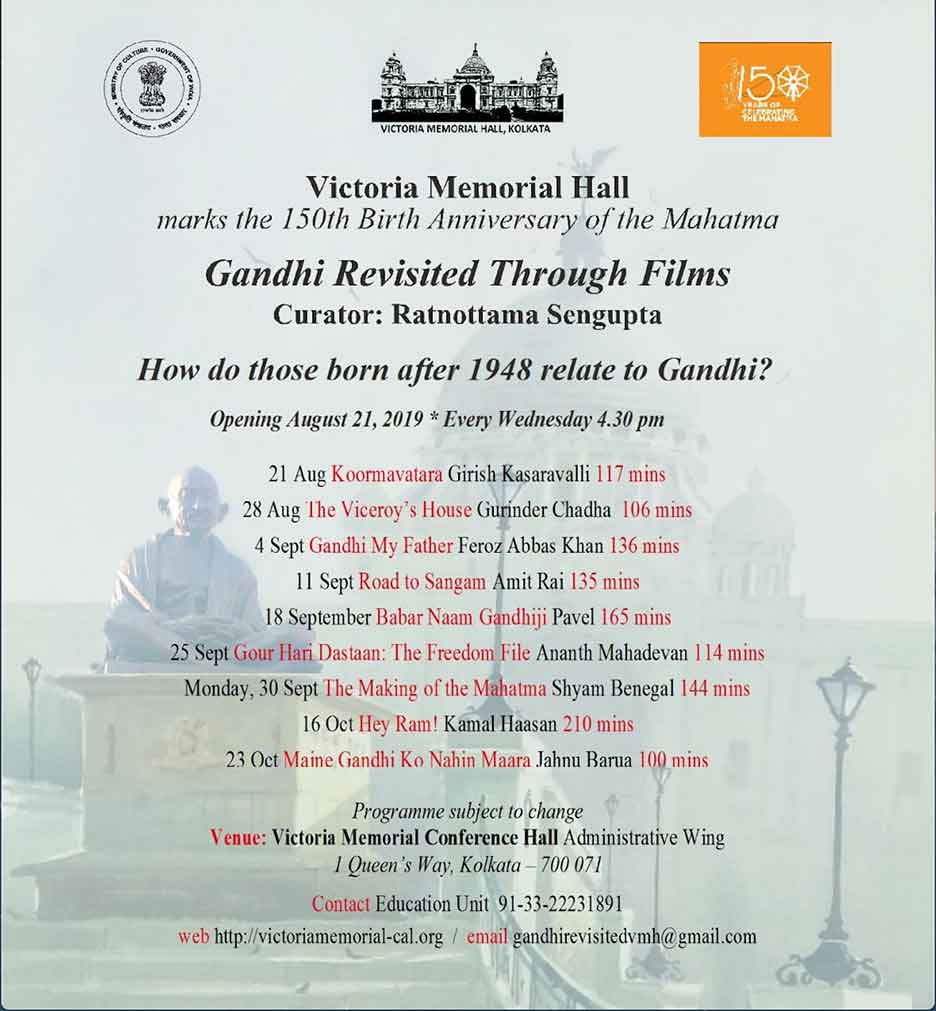

Most of the films discussed so far are ‘Biopic’. But what are men if not a bundle of thoughts? Great men are even more so. Their thoughts, their beliefs, their philosophies are not limited to their selves or even their immediate families. They are for society, for nations. Small wonder that we come to hail them as the Father of the Nation. This is what prompted me to curate two festivals so far – one, Gandhi Revisited (October 1-9, 2018/ India Habitat Centre) on how those born after 1948 view or perceive the Mahatma. Was he still a ‘Mahatma’? In a world overtaken by terror and violence, is the 20th century Bodhisattva – so called because of his crusade for Non-violence – still relevant? Or had the philosophy lived AND died by becoming a mere slogan for politicians to pay lip service with, while the average Indian is busy making money at the cost of conscience? Have Tolerance, and Honesty – another word for adhering to Truth – become forgotten hallmarks of moral fibre for us? If so, then what use the face on every currency note? And why name the high street of every city after MG? What harm, then, in dismantling the statues that adorn not only cities in India but elsewhere around the globe?

This is where we tread slippery ground. Allow me to quote Feroze Abbas Khan, director of Gandhi My Father. “Since a large number of film-going audience is young, we were advised to project the clash between the younger generation of Hopefuls and the older generation of Rigidity and Dogma.” That anti-Gandhi stance could have “relieved the young from the tyranny of principled action, conscientious choices, hard work, pursuit of excellence, compassion, non-violence etc etc…” Harilal could then be the newage hero who vanquished the Gandhian Goliath. The director did not walk this talk. Although his story could simply have a wronged son and an uncaring father, he did not reduce to this binary the complex relationship between a principled father and an aspiring son driven by social and political turmoil that turned Chhota Gandhi into a hand-tool of fanatics in Bombay and Calcutta. Because, the director says, “These were real people whose struggle is instructive for our lives.”

Gandhi, we all know, was one political leader who emphasized moral and ethical values in our actions, be it personal, professional, social or political. Allow me to quote Albert Einstein as he reacted to the Assassination: “He has demonstrated that a powerful human following can be assembled not only through cunning, of political manouevres, but through the cogent example of a morally superior conduct of life.” This prompted me to screen Girish Kasaravalli’s Kurmavatara (2012), where a clerk with striking physical resemblance to Gandhi is asked to enact him in a tele-serial. But when he starts thinking and behaving like Gandhi he is silenced. Gaur Hari Dastaan: The Freedom File (2014) devolves around Gaur Hari Das, who becomes a butt of jokes when he resorts to Satyagraha in Bombay, to get what is his right – a Tamra Patra honoring his participation in the freedom struggle. Learning from his protagonist’s second struggle within his own countrymen, Ananth Mahadevan came alive to the gravity of Gandhi’s resilience. “A man who never lost his dignity while asserting himself in the toughest period of the nation’s history will continue to disarm people…” he now believes.

In Babar Naam Gandhiji (2015) a street urchin is told that the man on the currency note is his father. But when he starts believing it, he is hauled up for fraud. So much for his being the Father of the Nation! On the other hand, Lage Raho Munnabhai (2012) gave a new term to our national lexicon when a Don trades Dadagiri for Gandhigiri. Through Uttam Chowdhury, the retired professor who is forgetting his own self, Maine Gandhi Ko Nahin Mara (2005) speaks of a society that is forgetting honesty and voice of conscience reducing the Mahatma to a statue or a postal stamp. It was Jahnu Barua’s way of venting his frustration at the fact that India was forgetting the jumlas and homilies Gandhi gave us. “We hardly realise that more than half the problems we face today is because of this,” he says, “and thereby we are killing Gandhi everyday…”

There are other films that could be in this club. Like, Road to Sangam (2009), where a devout Muslim mechanic in post Partition India, Hasmat Ullah is transformed when he is entrusted the job of repairing an old V8 Ford, that carried Gandhi’s ashes to the holy Triveni Sangam. Or Welcome Back Gandhi (2014) where A.Balakrishnan imagines what could transpire if the Mahatma were to live in India today.

Satyagraha, Sarvodaya, Ahimsa: Gandhi’s three big notions, principles, philosophies – call them what you will – are revisited in so many film that it is difficult to club them in one festival. In particular I have been intrigued by his attempts to wipe out Untouchability from the Indian polity. “Achhut!” That word should not exist in our world, I had unconsciously decided at the age of four when, as a part of the extended Bimal Roy family, I was watching Sujata (1959) based on a Subodh Ghosh story. A grandmotherly lady who is cuddling and cooing over a child this minute, transforms into an ogre who can throw it away because of that one word??

Six decades have gone by, and what do I see? The Depressed Classes who were dubbed Harijan to remind us there is Hari – god – in every soul, became Scheduled Caste under the Constitution, Dalit thanks to Dalit Panther movement, Other Backward Classes through Mandal but no, the stigma remains. Today increasingly there is a demand for greater and greater reservation in the name of Caste. Why are Untouchables still Dalit and not Harijan? This led me to curate the second festival, Caste After Gandhi: Harijan or Dalit? (Jamuary 2019/ IIC).

As scholars point out, Gandhi was not against the Varna system but he was against caste prejudices. The ancient classification of the Hindu society into the four Varnas reflected division of labour which is essential for the better functioning of a strong society. It entailed the moral obligation of Sarvodaya – welfare for all – rather than superiority of a privileged few since all kinds of work are important for the equality essential in an egalitarian society.

That may be why, even in 1930s, when the Mahatma walked amongst us, films like Achhut Kanya, Balyogini, Thyagabhoomi, Mala Pilla were focusing on this scar, this assault on humanity. In Achhut Kanya (1936), the Bombay Talkies film directed by the German Franz Osten, Brahmin Pratap and low-born Kasturi are ill-fated lovers sacrificed to social discrimination. This first reformist film on Indian screen was perhaps inspired by Gandhi’s Harijan, published from Yerwada Jail of Pune in 1933. The same year the Tamil screen featured Balyogini. When a Brahmin widow and her child are cast out by their wealthy relatives, she seeks shelter with a low-caste servant. This enrages the Brahmin villagers who set the house on fire. This film was made by Brahmins and cast a Brahmin in the lead role – so a group of Brahmins met in Thanjavur and declared the director outcaste. In reply he made Bhakta Cheta (1940) on a Harijan saint.

Mala Pilla (1938) in Telugu joined the crusade through another story of a Brahmin who falls for a Harijan girl. The social strife this causes is calmed only when a pandit is saved from fire by a Harijan. Thyagabhoomi (1939) was produced at the height of India’s freedom movement expressly to glorify the Mahatma’s ideals. Protagonist Sambu Sastri invites ostracism by sheltering Harijans in his home after a cyclone. The orthodox Hindus excommunicate him. His daughter comes away from a failed marriage. At one point a rich lady from Bombay anonymously donates Rs 500,000 for Sastri’s ashram – harking back to Gandhi’s own experience. Many twists and turns later Sastri’s daughter wears khadi, joins the Freedom Movement and gets arrested with her father and other freedom fighters. The story by Tamil writer Kalki Krishnamurty, financed and distributed by the movie mogul S S Vasan before he created Gemini Pictures, was banned after release by the British Government.

From its very beginning the New Indian Cinema of 1970-1980s focused on the topic. Samskara (1970) and Sadgati (1988) both scanned caste rigidities over the cremation of the dead. In Pattabhirama Reddy’s pathbreaking film, based on U R Ananthamurthy’s novel, the struggle is between a shuddha Brahmin and one corrupted by eating meat and sleeping with a fallen woman. The churning within the orthodox society led to the Madras High Court banning the film – the first Kannada film to suffer this fate. Sadgati, based on Premchand’s timeless tale, is on a black and white pitch. The Brahminism of the ‘superior soul’ is protected by a cord as he drags the dead Dukhia away from the Upper Caste habitation. To hell with dignity of the dead, when life doesn’t accord it to them!

In Bhavni Bhavai (1980) Ketan Mehta sets the tale of an untouchable’s revolt in a fairytale past but ends with a futuristic collage to show that a far more violent rebellion awaits us if untouchability is not ended peacefully, willingly, constitutionally. Note that this colourful, energetic folk drama came from Gandhi’s homeground.

Yet, merely five years later Damul (1985) shows that the Constitutional provision of voting too has been ursurped by the upper caste who had, for centuries, turned the low-born into bonded slaves and left them no alternative to freedom save death. Damul, written by Shaibal from Gaya, was directed by Prakash Jha who has fought three Lok Sabha elections – a proof of the fact that he has not lost his faith in the Constitution of India.

Damul, like Samskara before and Chauranga after it, showed caste and sexual oppressions are inevitably linked. In Chauranga (2014), a teenager who wants to go to school must instead tend to the pigs of a Brahmin who has sired him with a woman good only to clean their cowshed. Tragedy befalls the family when his elder brother tries to help him articulate his love for a Brahmin’s daughter. “But in recent years I have noticed there are not drummers in the villages. The newer generations are trying to move away and find new opportunities, mostly in the cities,” says director Bikash Ranjan Mishra. Growing up in Jharkhand gave him an insight into the inequities he addresses in the Khorta language film. He could be quoting Gandhi when he says, “I am angry about them but I don’t have to show them in my film.”

Masaan (2015) also shows the possibilities of a new dawn in the life of those born to the Doms of Kashi ghats. However Nagraj Manjule clearly doesn’t subscribe to this optimism. Making films from his experience of growing up in a Dalit area of rural Maharashtra, he debuted with Pistulya, showing a Dalit family’s disdain for a boy’s desire to attend school. Fandry (2013) focused on the economic hardship faced at the hands of Savarna families. And Sairat showed that neither education nor economic development has wiped out caste prejudices among the so called high-born.

So, 70 years after Gandhi’s mortal remains were consecrated, Rajghat is a tourist attraction, and khadi striving to make place on the fashion ramps. The meantime has seen the implementation of the Mandal Commission Recommendations, yet the caste narrative of the Depressed Classes has not lost its edge. Satyameva Jayate highlighted on the small screen that honour killings are still forcing young lovers to check their ‘caste compatibility’. And 80 years after Achhut Kanya, Sairat – the Marathi super-grosser reportedly being remade in every Indian language besides Dhadak in Hindi – still ends the Rome-Juliet way. Tragically, their finale is rooted in caste inequity, not class difference.

Was it prophetic when Ashok Kumar, a Brahmin in Achhut Kanya, says “Bhagwan, tuney mujhe bhi kyun na Achhut banaya?” For even today, the ‘Maila Anchal’ of Bharat Mata is not wiped clean. Instead more and more institutions are being brought under ‘reservation’. Surely it is because discrimination and humiliation are still the given in godforsaken villages of India, as we see in Chauranga and Fandry. So what happened to Gandhi’s belief that “True Independence will dawn only when caste is wiped out?

Gandhi did not leave a sect behind him. He did not approve of ‘Gandhism’ for he did not claim to have originated any new principle or doctrine. “I have simply tried to apply in my own way the eternal truth of our daily life and problems…” So it is up to you and me to change this narrative. What might change the ground reality of casteism? Not mere conferring of right to vote – politics has proved. Will technology work the magic? After all, machines are taking over crematoriums, and leather works, and scavenging? Will quality education change the situation, when it is available at the grassroots, in the backwaters and the municipal schools? Will the computer controlled world where you do not see any human face, let alone touch them, work the revolution? Or the Capitalist Utopia where everyone is rich, famous and powerful?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.