Even before Satyajit Ray made history with his first film ‘Pather Panchali’ in 1955, he had written a script based on Rabindranath Tagore’s novel published in 1916, “Ghare Baire” (The Home and the World) [1], that was to have been directed by a friend Harisadhan Dasgupta according to the official website of Ray [2]. The Tagore novel continued to fascinate him though. In the early 80’s he revived the project, produced by NFDC, with a new script as he wasn’t happy with the earlier version. Despite suffering a heart attack and undergoing a bypass surgery, he got the film completed by his son Sandip Ray under his supervision. It was nominated for Palme d’Or at Cannes film festival 1984 although it didn’t win the award. It received positive reviews from foreign film critics such as Pauline Kael [3], Roger Ebert [4] and Vincent Canby [5]. However, ‘Ghare Baire’, in general, didn’t get the kind of acclaim that Ray’s ‘Charulata’ (1964), yet another adaptation of Tagore with a love triangle, received. In this Satyajit Ray centenary year, it is richly rewarding to have a relook at ‘Ghare Baire’ in which the master scaled new heights.

Background

Before delving into the novel and the film, there is a need to understand the effect the Swadeshi (meaning: of one’s own country and not imported) movement in the beginning of the 20th century had on Tagore which led to his writing of the novel. Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal in 1905 drove a wedge between Hindus and Muslims and gave rise to the Swadeshi movement and boycott of British goods. But Indian made goods were much more expensive, widening the rift between them as most of the Hindus could afford the boycott unlike most of the Muslims.

In his remarkably well researched and comprehensive book, “Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye”, Andrew Robinson has written elaborately on ‘Ghare Baire’ in the chapter “The Home and the World”. Robinson has written about Tagore and his family’s involvement during the beginning of the movement: “[Swadeshi movement’s] most enduring positive legacy is, by general agreement, the body of stirring and beautiful songs composed by Rabindranath Tagore as a Swadeshi leader, one of which is sung by Sandip in the film… Rabindranath and other members of the Tagore family had been among the earliest Bengalis to experiment with Swadeshi businesses” [6]. Tagore distanced himself from the movement when it grew violent in 1906, attracting criticism from the leaders. Robinson writes that Nikhil in the novel speaks for Tagore, quoting Satyajit Ray[6].

“Ghare Baire” the Novel

Set in the turbulent period that witnessed the Swadeshi movement in Bengal, the novel deals with the lives of an aristocratic couple Nikhil and Bimala who have been shaped by the ideals of Bengal renaissance. Nikhil’s friend Sandip, an anti-British nationalist with extremist views enters their household. A truly modern Nikhil encourages Bimala to come out of her quarters (zenana). He convinces her that only by meeting and recognizing each other in the real world there will be true love. Enticed by Sandip, she is willing to help his Swadeshi cause even at the cost of betraying her husband. But, as the events unfold, she comes to know of the violence unleashed by his rhetoric.

The title of the novel (“The Home and the World” in English) has multiple meanings. The obvious one is the aristocratic household and the outside world in turmoil that has an impact on the former. To look at yet another meaning, the prominent theorist Partha Chatterjee has written insightfully in his book “The Nation and Its Fragments” [7] that the nationalist discourse condensed material/spiritual distinction into outer/inner dichotomy. He has elaborated that the inner/outer distinction divided the social space into home (ghar) and the world (bahir). Chatterjee has come up with how they were represented: The world is the domain of the male open to the influence of the coloniser and the home is the domain of the woman which cannot be colonized. This dichotomy explains the way upper class women were confined, in continuation from an earlier period onwards, to the zenana, also called andaramahala. The progressive Nikhil wants Bimala to come out of the zenana, which is the home, to the outer apartment in their palace – the world to meet other men such as Sandip and continue to love her husband if he is worthy of it.

The names of the three main characters coined by Tagore fit their personalities. Nikhil means “whole’ which suits the aristocrat who is for universal brotherhood. Sandip means “kindling, arousing or exciting” which denotes the Swadeshi leader. Bimala means “pure” which befits Nikhil’s wife who attains purity in her love after undergoing a tortuous test at a heavy price. Their full names come through in the film: Nikhilesh Choudhury, Sandip Mukherjee and Bimala Choudhury. Perhaps it is as per the novel in the original Bengali as the English translation doesn’t give the full names.

The novel’s structure is that of the first-person accounts of the three main characters Bimala, Nikhil and Sandip who take turns to come up with their stories. Each one is given a few chapters then the novel moves to the other and so on in a round robin sequence. We get an insight into their minds and also the character progression of Bimala. The novel starts with Bimala’s story and ends with it, for she is the one who is most impacted by the events.

Apart from the main themes reflected in its title, there are several recurring themes in the novel such as Bande maataram (meaning “Hail Mother”, the opening words of a song, that extols India as the Mother, written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the famous Bengali novelist), Bimala as Goddess, and characters misinterpreting the Bhagavad Gita. On Bande maataram Nikhil makes a case for universal brotherhood as against narrow nationalism. Sandip calls Bimala as goddess the very first time he meets her. His repeated addressing of her as goddess instils the self-image of the Shakthi of womanhood in Bimala. As she says in her story, Sandip subtly interweaves his worship of the country with his worship of Bimala making her “blood dance, indeed, and the barriers of my hesitation totter”. In this way Sandip manipulates her to look upon herself as the deity that will give boon to the worshipper by giving away money. Both Sandip and the young revolutionary Amulya misinterpret the Bhagavad Gita in their own way to justify their actions.

Tagore’s novel was praised by the playwright Bertolt Brecht (“a fine, powerful piece of work”), misread and panned by the Marxist critic György Lukács, and criticized as well as appreciated by the novelist EM Forster [6]. Forster came up with an observation that “the characters have to be accepted as vehicles for Tagore’s always interesting philosophy and not be required to function as individuals with a life of their own, which they are not” although Tagore appears to have based some of the characters in the novel on real people including himself. In “Ghare Baire” Tagore took up a couple of subjects of importance for him – emancipation of women and Swadeshi – and weaved a story around them in his poetic style. Because of its preoccupation with ideas, the novel appears to deal with types. It is essentially a novel of ideas where the clash of the personal and the political is handled with such intensity thanks to the force of conviction Tagore must have attained from his own experience during the Swadeshi movement.

“Ghare Baire” the Film

Satyajit Ray made the film dramatic by changing the structure in his adaptation of the novel. Ray’s ‘Ghare Baire’ begins with the end: Bimala (Swatilekha Chatterjee (Sengupta)) is in tears after the tragic death of Nikhil (Victor Banerjee). There is the sense of foreboding doom accentuated by the theme music. The novel is preoccupied with the minds of the three characters so it is told as a series of first-person narration of them. Ray also brought in these voices but he simplified the structure for the film by having just two sections for Bimala and one section each for Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee) and Nikhil. Bimala’s first story, lasting for 57 minutes, starts with about 2 minutes of her narration in which she recounts how she got married and entered Nikhil’s palace (reminding us of yet another outstanding Ray film ‘Jalsaghar’ (1958) which had a palace in ruins but the palace in ‘Ghare Baire’ is lived-in and very much in use). The rest of the section is in her point of view. There is her voice-over during the crossing of the passage with stained-glass windows by her for the first time. Sandip’s section, Nikhil’s section and Bimala’s second section start with a very brief monologue after which the rest of the sections are in their points of view. The durations for these sections are 15 minutes (Sandip’s), 15 minutes (Bimala’s second) and 12 minutes (Nikhil’s) respectively. The remaining part of the film running for about 50 minutes is in the third person omniscient point of view.

Analysing the structure of the film helps in understanding how it works. Although it is Nikhil who encourages Bimala to come out of the zenana, once she does it, it is mainly Bimala and Sandip who drive the events. Nikhil is a passive participant. In his section, Nikhil takes stock of the turbulence caused by Sandip but he doesn’t want to force himself on Sandip and Bimala. The last section shows the trouble sparked off by Swadeshis leading to communal violence, Nikhil asserting himself, Sandip’s leaving and the tragic end of Nikhil. Ray has invented several scenes of his own and enlarged the scenes, which are not in detail in the novel such as the speech delivered by Sandip for the benefit of the public. The Nikhil household has been created with all its period detail. The dialogue is almost entirely written by Ray using bare minimum lines from the novel. The conversations among Nikhil, Bimala and Sandip are invested with Ray’s touch of humour.

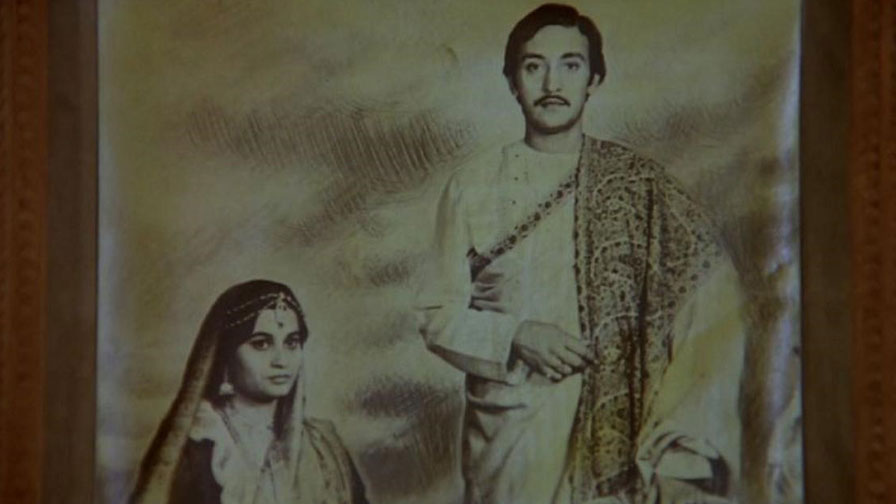

Satyajit Ray displayed his mastery of filmmaking right from his early films reaching a highpoint in ‘Charulata’. In ‘Ghare Baire’ he goes even beyond that peak to a higher level. The film is a masterclass which makes it worthwhile to see some of the scenes in detail. The title scene opens with the Swadeshi bonfire in the background accompanied by the ominous theme music on the sound track which ends with the cries of Bande maataram. Fire is a recurrent motif in the film. From the fire of the title scene, it cuts to the opening scene which shows fire raging in the estate at a distance, ignited by the communal violence. Then the camera pans left to the close-up of the teary eyed Bimala narrating her story saying “What was impure in me has been burnt to ashes”. No wonder she is named Bimala (pure). The camera then tracks closer to her as she says “What remains in me I dedicate to him who received all my failings in the depths of his stricken heart. Now I know there is not one like him”. Then there is a cut to a much bigger close-up of Nikhil with his wedding headgear as we hear Bimala saying on the sound track “It was ten years ago that I first met him”. The camera zooms out and cuts to a younger Bimala bedecked in bridal finery, perhaps being carried to Nikhil’s palace. On the soundtrack we hear Bimala saying, “He was the son of a noble family and I was his bride.” It cuts to her face in the huge picture of the couple – sepia tinted – and then zooms out to show both of them.

Then there is a cut to Nikhil’s sister-in-law (Gopa Aich) in white and we learn from Bimala’s commentary that she was already a widow when Bimala entered the household. The camera pans right to show Bimala as a servant plaits her hair. The camera tracks back to show both of them and the maids sitting in the corridor of the aristocratic mansion. The sister-in-law is clapping and swaying to the song played on the gramophone. This is an excellent opening which gives an introduction with economy and style.

The scene in which the progressive Nikhil tries to convince his wife Bimala to come out of the zenana and meet his friend could have easily become heavy handed but Ray pulls it off with his deft touch! Bimala tries on various blouses made of imported cloth and designed by her to the appreciation of the sister-in-law who also comments on her foreign clothes and perfumes. Nikhil enters the scene, admires her dress and the couple sing a few lines of a Bengali song together. Is there a better way of capturing marital bliss? Ray infuses humour in the intelligent conversation which goes on as Bimala keeps trying on the clothes received from the tailor. Nikhil would like his beautifully dressed wife to be seen by his friends. Confining women to the house was not a Hindu custom in the past he says. He thinks that the Muslims introduced the custom. Towards the end Bimala hums the English song (Tell me the tales that to me were so dear, Long long ago, long long ago) she has learnt from her British governess Miss Gilby (Jennifer Kendal). Perhaps Ray suggests here that by now she is exposed to new ideas and she is open to them. This is the time when Nikhil tells her that he’ll be proud to persuade her to meet his friends. Bimala asks him whether he means the one in a photo on the table. It is that of Sandip whom Nikhil calls a genius. Ray manages to include a brief introduction to the Swadeshi movement when Nikhil is surprised that his wife knows about the movement and quizzes her about it. Bimala comes to know from her husband that so many articles in her room are imported: the thread with which her saree is woven, the brush, the mirror, the comb, the hairpins, the perfumes, the bottles made of cut glass, the table and the furniture. The marital bliss evoked in this scene is going to be ironically ruined once Bimala comes out of her confinement. It is an example of how set design, costumes, lighting, camera work, dialogue, competent acting and music (although very little in this scene) work together under Ray’s direction to make a memorable scene.

The meeting with Miss Gilby – who has a head injury after a schoolboy, influenced by Swadeshi, hit her head with a stone – conveys the hatred for the British that endangers innocent people. Miss Gilby leaves putting an end to all the learning of Bimala: singing, piano, English and etiquette. This scene is done in just one shot with the three of them in a triangular composition.

It is followed by the arrival of the demagogue Sandip at Nikhil’s estate to deliver a speech that fascinates Bimala. She sees him carried by Swadeshis on their shoulders through the grille from the first floor of the palace. As a leader of the Swadeshi movement Sandip captures the imagination of the public. Bimala too falls for his speech lasting for 4 minutes – written and shot so well by Satyajit Ray creating an impact. Sandip’s oration starts with a long shot of him, shot from behind the audience after which there is a medium shot of him which zooms into a close-up. The camera pans to show the first floor of the building from where Bimala is watching him from behind the screen. Cuts to Bimala’s profile and zooms into her. Cuts to her point of view shot of Sandip through the grille. Close-up of Sandip from the front, shot in low angle. Cuts to her profile shot and the camera zooms into her. Cuts to her point of view shot of Sandip through the grille and the camera zooms into him. Long shot of Sandip from behind the audience. Close-up of Sandip shot in low angle. Bigger close-up of Sandip in low angle. Cuts to Bimala’s profile and zooms into her. Cuts to close-up of Sandip. Long shot of Sandip from behind the audience from an elevation. Camera comes down the crane and zooms into him as his speech reaches a crescendo. He ends his speech with the slogan Bande maataram – “sacred mantra” as he calls it – which is repeated by the audience in which we can see his followers in their uniform. This scene shows how Bimala is bowled over by Sandip’s speech and it leads to her taking up the cause of Swadeshi. But his call for boycott of cheap foreign goods wouldn’t have gone well with the minority community which was relatively poor. The religious references in this scene such as the saffron uniform and the “sacred mantra” Bande maataram which hails the nation symbolised as mother goddess would have distanced it further.

A scene which can be called pure cinema is the one in which Bimala, accompanied by Nikhil, crosses the passage and enters the outer apartment. The novel simply says that Nikhil called Bimala to introduce the guest. For the film medium, capturing the moment of crossing is important and Ray has done it with his touch of mastery accompanied by a Tagore tune that celebrates the moment albeit with a touch of pathos. This scene lasts for about a minute. It starts with the long shot of the inner corridor with the door leading to Bimala’s quarters at the end closed. There is the voice-over of Bimala which says “On November 15, 1907, the young mistress of the Choudhury house defied all convention and stepped into the passage leading to the outer apartments.”. The door opens and Bimala and Nikhil come out. It cuts to the close-up of their feet as they set foot in the inner corridor. Music starts. Cuts to long shot of the corridor as they walk slowly and gracefully towards the camera. As they reach the end, it cuts to the long shot of the outer corridor with Bimala and Nikhil at the entrance at the other end. Camera slowly tracks to the right and moves towards them as they are walking forward. When they go out of the left of the frame, there is a cut to the shot of them framed by two pillars and the camera tracks to the left as they continue to walk forward gracefully. They go out to the left of the frame. Cuts to the medium shot of Sandip in the hall who turns and looks surprised. Music ends. Cuts to the two entering the hall and Bimala folding her hands greeting Sandip with “namashkar”.

In this first meeting with Bimala, Sandip realizing that she is interested in the Swadeshi movement, attracts her to his cause by singing a song “Bidhir Badhon Kaatbe Tumi” written by Rabindranath Tagore when he supported the movement. Tagore’s song asserts that the weak will rise up, however mighty the British are. Bimala agrees to join Sandip’s cause. The scene ends with the shot of the ashtray in which the smoke emanates from the cigarette stub left by Sandip, indicating the stirring passion in her. Nikhil has been shown to be passionate about Bimala but it looks like there is no physical intimacy between them except Nikhil keeping his head on her shoulder and holding her hand. In a film which has kissing scenes to show physical intimacy, the only time they kiss each other is towards the end of the film. The couple are childless and their lack of a child is not touched upon by both the novel and the film. This is particularly striking in the film as Ray has added so much detail. Perhaps it is not an issue that will be raised openly in an upper-class household. The childlessness and the lack of physical intimacy between Nikhil and Bimala might have driven Bimala to the charismatic Sandip who woos her.

In their second meeting Bimala goes to see Sandip without Nikhil accompanying her. As asked by Sandip, Bimala sits next to him in the sofa. Sandip has decided to keep their estate as his base with him as a bee working for Bimala the Queen Bee. Sandip finds a hairpin in the sofa and keeps it in his pocket. This is reminiscent of Satyajit Ray’s ‘Apur Sansar’ (1959) in which there is the use of the hairpin that Apu takes out from the bed to suggest the physical intimacy between Apu and his wife. Here the relationship developing between Sandip and Bimala is captured by this device of hairpin which Sandip says is the only foreign item he’ll keep with him. He convinces her to ask Nikhil not to let foreign goods sold in his market. Later she talks to Nikhil about banning foreign goods in his market. Nikhil cannot stop the poor Muslim traders from selling the much cheaper foreign goods as nobody will buy the costlier Indian goods which were of inferior quality at that time. He also tells Bimala that he doesn’t share the feeling of Swadeshis for an abstract idea of the country as the mother.

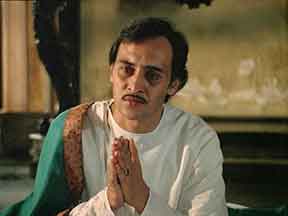

Sandip’s story starts with his close-up – his face lit by the raging bonfire nearby – as he comes up with a brief monologue in which he says, “OnIy what I can snatch away by force is mine”. This story is all about Sandip’s activities so Bimala is kept out entirely. Sandip happens to meet Nikhil and the school headmaster (Manoj Mitra) who voice their disapproval of what Sandip has been doing in the estate. Sandip gives a speech at Nikhil’s market which fails to persuade the traders. A boat can be seen in the river in the background. There is a brief monologue of Sandip which says that he has to use other means. The traders are robbed of their goods which are set to bonfire by Swadeshis. The manager of Nikhil’s estate is surprised to see that Sandip smokes foreign cigarette. That’s the only exception he makes to Swadeshi Sandip claims. Sandip’s attraction for foreign medicine in the novel has been replaced by foreign cigarettes in the film. As they speak, we can see a boat sailing in the river in the background. They decide to put an end to the supply of foreign goods by sinking the boat of Mirjan.

Bimala’s second story starts with her monologue revealing her attraction to Sandip, followed by her third meeting with Sandip in which Bimala moves about more freely in the room. Nikhil has been kept out of this section as it is largely about her growing relationship with Sandip and not having much with Nikhil. In her first meeting with Sandip she is seen sitting along with Nikhil. In the second one she meets Sandip alone and she is nervous because Sandip makes her sit next to her. She is relieved when Sandip lets her leave. Satyajit Ray has explained the third meeting between them which helps to understand his method: “… she has all the time in the world; therefore, she doesn’t sit down. She walks, first to the window, sings, sits down at the piano, and then walks again, takes her time in front of the mirror and then there’s a conversation. And then there comes a point where she’s offended by something Sandip suggests and she wants to leave and then they really come together. It was necessary to have a point for them to come together and here was a perfectly logical reason because Sandip naturally wants to prevent her from leaving, and he comes as close as possible to an embrace, but it’s not yet time for an embrace because the relationship hasn’t got to that point yet. Anyway, he holds her hand and she has to say ‘Please let me go’. And there’s the slight suggestion that he’s holding her hand so tight it’s actually hurting her. And then she goes… Psychology dictates her movement and therefore the movement of the scene is dependent on the relationship between the two characters” [6].

Nikhil in his story starts with a monologue, wondering whether he has the strength to bear what is going on. Both Bimala and Sandip have been kept out of this scene except for a fleeting glimpse of Bimala that Nikhil has of her standing in the corridor and staring outside. This section is about what Nikhil is going through. The school headmaster is worried about the worsening situation. Nikhil says that he has read about preachers from Dacca stirring up the locals. He also feels for the way the minority community has been treated. The headmaster tells him to ask Sandip to leave the estate. His sister-in-law too feels the same. She tells him to see the result of freeing Bimala from her moorings. Nikhil says that it was not a foolish notion. She requests him to ask Sandip to leave. Nikhil tells her that if he asks Sandip to leave, he’ll find Bimala regretting it because it wouldn’t be her decision. That would be unbearable both for her and for him. Nikhil says that he can’t do it out of his own selfishness. Ray gives Nikhil the least screen time in the film to underscore his passive approach.

The rest of the film is in the third person omniscient point of view. There is Bimala’s fourth meeting with Sandip in which she appears to come on her own without being called by him. She sees him playing the piano and singing a few lines of yet another Tagore song, “Chalre Chal Sabe Bharat Santan” (Onward, sons of India, the MotherIand calls). Bimala picks up his foreign cigarette packet and says “I gather you have won the hearts of many women both Swadeshi and foreign”. Indicating that she has fallen in love with Sandip, there is a close-up of a figurine of lovers on the table she walks up to. Sandip breaks into singing the song “Bujhte nari naree ki chay” (Who can ever fathom a woman’s ways?) written by Akshay Kumar Borai. The playback singer for all the three songs sung by Sandip in the film was Kishore Kumar, one of the most popular singers of Hindi film songs. Bimala is shocked to know that Sandip may leave their estate. After Sandip says he needs five thousand rupees, Bimala pleads with him whether he’ll stay if she gives him the money. She says “I did it all for you”. She doesn’t realise that all the talk of him as a bee working for the Queen bee was to flatter her. She is so emotionally attached to him that she can’t think of him leaving the palace. This brings both of them together and Sandip kisses her. It was perhaps the first time there was a kiss in a Ray film.

Nikhil goes out on horseback in his riding attire inspecting the ghost village. There is absolute quiet as everybody has gone to the mosque. As Nikhil approaches the mosque, he starts hearing the speech of the preacher who stirs up the peasants. This scene is not there in the novel although it is alluded to. Back in his palace the headmaster rushes to him when a shot is heard. Nikhil assures him that he’ll tell Sandip to leave. The fifth meeting between Bimala and Sandip starts with a kiss. She gives him the money. But things take a turn as Nikhil comes to the room and tells Sandip firmly that he doesn’t want him to stay there any longer as in Tagore’s novel. Nikhil says that he is aware of what Sandip has caused: setting fire to peasants’ barns and sinking Mirjan’s boat. For the first time, Bimala comes to know of the violence unleashed by Sandip. She turns her back to him. Sandip asks her whether she wants him to stay or not. This part is not in the novel. She doesn’t answer his question but asks him to inform Amulya (Indrapramit Roy), his deputy, to meet her. From Amulya, Bimala comes to know that Sandip asked her for more money than needed and that Sandip is a big spender who always travels first class. The sixth meeting shows a clear break between Bimala and Sandip. Now Bimala cares only for Nikhil’s safety and no one else matters for her. In the seventh meeting Sandip returns the jewellery box, takes the money and bids goodbye. Now that the riot has erupted, he has to do his proverbial escape. Despite his charisma and commitment to Swadeshi, Sandip comes across as an opportunist. In contrast the young Swadeshi Amulya is more committed as he would rather stay in the village and face the situation. Thus, over these seven meetings Satyajit Ray has developed the growing and changing relationship between Bimala and Sandip with great skill.

This is an unusual love story in which we feel sympathetic to Bimala who is unfortunate. By the time she sees through Sandip and truly loves Nikhil, he kisses her and leaves on horseback to quell the riot. There is a shot of raging fire at a distance seen from the balcony of his palace and the camera zooms in. The next morning from the same balcony the camera shows the headmaster and others coming slowly in a procession towards the palace to beating of drums and mournful music. They are followed by a palanquin and Nikhil’s horse without a rider. This is a departure from the novel which is open ended. The doctor in the novel can’t say yet on Nikhil’s condition. The wound in the head is a serious one. In the film he is dead. While it makes the film dramatic and gives a circular structure, Tagore’s open ending left some hope however faint it was. The camera moves to the left to show the grief stricken Bimala standing against the wall and moves towards her for a bigger close-up. There is a dissolve which shows her without the bindi in her forehead. In yet another dissolve it shows her in white saree worn by widows. Then the camera tracks back a little showing her in a medium shot.

This is an unusual love story in which we feel sympathetic to Bimala who is unfortunate. By the time she sees through Sandip and truly loves Nikhil, he kisses her and leaves on horseback to quell the riot. There is a shot of raging fire at a distance seen from the balcony of his palace and the camera zooms in. The next morning from the same balcony the camera shows the headmaster and others coming slowly in a procession towards the palace to beating of drums and mournful music. They are followed by a palanquin and Nikhil’s horse without a rider. This is a departure from the novel which is open ended. The doctor in the novel can’t say yet on Nikhil’s condition. The wound in the head is a serious one. In the film he is dead. While it makes the film dramatic and gives a circular structure, Tagore’s open ending left some hope however faint it was. The camera moves to the left to show the grief stricken Bimala standing against the wall and moves towards her for a bigger close-up. There is a dissolve which shows her without the bindi in her forehead. In yet another dissolve it shows her in white saree worn by widows. Then the camera tracks back a little showing her in a medium shot.

Criticism on ‘Ghare Baire’ the film

One of the criticisms on the film was whether it faithfully depicted the Swadeshi movement. After the advent of Gandhi, the movement got revived by him as a non-violent movement but the film covers the earlier period as in the novel. Tagore wrote it in 1912 based on his experience in the movement from 1905 to 1906. So, the film must be seen confined to that period.

‘Ghare Baire’ is usually compared with Ray’s highly acclaimed ‘Charulata’ the Golden Bear award winner at Berlin. It is as though people wanted yet another ‘Charulata’ from Ray. A common criticism made in comparison with Ray’s earlier masterpiece is that ‘Ghare Baire’ is too ‘talkative’ [6]. ‘Charulata’ is a very good example of a Ray film that narrates the story of individuals in their naturalistic setting with acute observation of details and less talk. In his book “The Cinema of Satyajit Ray”, the highly respected film critic Chidananda Das Gupta wrote about the film: “Ray’s analytical method, his ability to reveal the mental event with exactness and with few words reaches its height in ‘Charulata’ “ [8]. In his novel “Ghare Baire”, Tagore had based Nikhil on himself and he appears to have modelled Sandip after Swadeshi leaders he came across. Satyajit Ray added all the details and portrayed the characters in flesh and blood. Yet, because of the strong ideas behind the story, the characters may appear as types. While ‘Charulata’, a chamber film like ‘Ghare Baire’, has some scenes which are great examples of visual narration, ‘Ghare Baire’ deals with a couple of subjects, viz. women’s emancipation and Swadeshi, involving conversations but Ray makes them intelligent and witty. Comparatively ‘Ghare Baire’ has more outdoor scenes than ‘Charulata’, setting its domestic drama against the disturbances happening in the outside world which are of relevance even today. Vincent Canby has rightly called ‘Ghare Baire’ a “sweeping chamber-epic” [4].

The characterization of Nikhil and Sandip in the film has been criticized. Nikhil comes out self-critical in the following passage in the novel: “I could only preach and preach, so I mused, and get my effigy burnt for my pains. I had not yet been able to bring back a single soul from the path of death. They who have the power can do by a mere sign. My words have not that ineffable meaning. I am not a flame, only a black coal, which has gone out. I can light no lamp. That is what the story of my life shows, my row of lamps has remained unlit” [1]. Andrew Robinson, in his book on Ray, wonders whether Ray didn’t find fault with Nikhil as he looked upon Nikhil as Tagore [6]. But this self-critical passage which fits the poetic style of the novel might have looked out of place in the film. Not that Nikhil in the film is faultless. As Vincent Canby [5] has pointed out, Nikhil comes out egocentric as one of the reasons he wants Bimala to come out of her zenana is that he wants her to evaluate him in comparison with other men. He wants to be found to fare better than others and loved by Bimala. Also, for his selfish reason, as he says, he does not force himself on Bimala and Sandip (till the riot breaks out). As Roger Ebert has written “all the time her husband stands by, his detachment becoming one of the fascinations of the movie” [4]. Pauline Kael has likened the core situation in the film to that in James Joyce’s play “Exiles” [3].

Ironically, Nikhil’s extreme idealism leads to pushing Bimala in Sandip’s embrace. Andrew Robinson has written that “the Tagores went in for such a behaviour, according to Ray” citing an actual example in which Tagore’s eldest brother Satyendranath Tagore pushed his friend to sit on his wife’s bed under a mosquito net and left them to get acquainted [6]. A more common sensical man in Nikhil’s place would have kept Bimala away from a philanderer like Sandip. Nikhil’s idealism also makes him politically naive. Somebody who understands the politics wouldn’t have let Sandip stay in his house, arouse the Swadeshis against the poor traders, use Nikhil’s manager to get Mirjan’s boat sunk and cause a riot in his estate. Nikhil’s heroic rising to the occasion to quell the riot only results in riding to his death. However, as Roger Ebert has written, Nikhil’s detachment is a fascination in the movie. It elevates the film to a visionary level. Victor Banerjee excels in the role of Nikhil with his superlative performance. It’ll go down as one of the all-time great performances in Indian cinema.

Ironically, Nikhil’s extreme idealism leads to pushing Bimala in Sandip’s embrace. Andrew Robinson has written that “the Tagores went in for such a behaviour, according to Ray” citing an actual example in which Tagore’s eldest brother Satyendranath Tagore pushed his friend to sit on his wife’s bed under a mosquito net and left them to get acquainted [6]. A more common sensical man in Nikhil’s place would have kept Bimala away from a philanderer like Sandip. Nikhil’s idealism also makes him politically naive. Somebody who understands the politics wouldn’t have let Sandip stay in his house, arouse the Swadeshis against the poor traders, use Nikhil’s manager to get Mirjan’s boat sunk and cause a riot in his estate. Nikhil’s heroic rising to the occasion to quell the riot only results in riding to his death. However, as Roger Ebert has written, Nikhil’s detachment is a fascination in the movie. It elevates the film to a visionary level. Victor Banerjee excels in the role of Nikhil with his superlative performance. It’ll go down as one of the all-time great performances in Indian cinema.

Tagore has poetic lines for Sandip too. Bimala says the following about Sandip in the novel: “There is much in Sandip that is coarse, that is sensuous, that is false, much that is overlaid with layer after layer of fleshly covering. Yet, yet it is best to confess that there is a great deal in the depths of him which we do not, cannot understand, much in ourselves too. A wonderful thing is man” [1]. This passage has no place in Ray’s film perhaps for the same reason why Ray didn’t have the poetic monologue of Nikhil. But Ray cast Soumitra Chatterjee, who played Apu in ‘Apur Sansar’ and Amal in ‘Charulata’ in the role of Sandip. As Andrew Robinson has written, Soumitra Chatterjee was fiftyish when ‘Ghare Baire’ was made and he lacked a little in elan [6]. However, Soumitra Chatterjee’s image that we hold in our mind – especially that of Amal to whom Charulata is drawn to in Ray’s ‘Charulata’ – a somewhat similar film with a love triangle – makes him charming although he plays an antihero here. Thanks to his image, Satyajit Ray’s casting of Soumitra Chatterjee as Sandip lends some positive aspects to the character. As played competently by Chatterjee – although his age was not on his side for the role – Sandip’s oratorical skills, his singing and his revolutionary posture appeal to Bimala and she falls for him. Ray’s master stroke is to let us see Sandip through Bimala’s point of view in the first 57 minutes. Like Bimala, we too fall for him. It is only after that we come to know of his designs from his story. As Nikhil describes Sandip, “despite all his gifts, he hasn’t really accomplished anything” and Sandip comes out as an opportunist. This attracted criticism that unlike ‘Charulata’ the characters in ‘Ghare Baire’ are in black and white. But in ‘Charulata’ there is the character of Charulata’s elder brother, Umapada, who swindles Charulata’s husband Bhupati of his money, destroying his newspaper. Since Umapada is a peripheral character unlike Sandip, a main character in ‘Ghare Baire’ who does the damage, ‘Charulata’ may appear more nuanced.

Yet another criticism on the film was the casting of Bimala. Perhaps people wanted to see yet another beautiful and talented actor like Madhabi Mukherjee to play the role. But in Tagore’s novel, Sandip talks about Bimala in his story in the following way: “Her tall, slim figure these boors would call “lanky”. Her complexion is dark, but it is the lustrous darkness of a sword-blade, keen and scintillating” [1]. Madhabi Mukherjee didn’t fit the description of Bimala in the novel. It would have been very difficult to find an actor who could perform well as well as meet with Tagore’s description. Perhaps Ray might have still cast a great actor like her but she was older for this part in the early 80s. Swatilekha Chatterjee (Sengupta) didn’t fit the description either. It seems she was “a stage actress he [Satyajit Ray] saw in 1981, had both personality, command of Bengali, and ‘the intellect to understand what she was doing’” [6]. Swatilekha Chatterjee (Sengupta) has the maximum screen time in the film among the three main actors. It’s one of the most difficult female roles in Indian cinema which she enacted admirably for a newcomer. To quote Pauline Kael, “Bimala is girlish and coquettish in the early scenes in the women’s quarters, and part of the fascination of the movie is that Swatilekha Chatterjee grows with her role, and becomes more absorbing the longer you see her. She is not a mere ingénue; she’s a full-bodied, rounded beauty, and her Bimala has an earthy, sensual presence” [3]. Unlike in ‘Charulata’ in which the protagonist’s blossoming of a writer alone is hurried though with a montage, ‘Ghare Baire’ brings out Bimala’s character development in all its detail.

Yet another criticism on the film was the casting of Bimala. Perhaps people wanted to see yet another beautiful and talented actor like Madhabi Mukherjee to play the role. But in Tagore’s novel, Sandip talks about Bimala in his story in the following way: “Her tall, slim figure these boors would call “lanky”. Her complexion is dark, but it is the lustrous darkness of a sword-blade, keen and scintillating” [1]. Madhabi Mukherjee didn’t fit the description of Bimala in the novel. It would have been very difficult to find an actor who could perform well as well as meet with Tagore’s description. Perhaps Ray might have still cast a great actor like her but she was older for this part in the early 80s. Swatilekha Chatterjee (Sengupta) didn’t fit the description either. It seems she was “a stage actress he [Satyajit Ray] saw in 1981, had both personality, command of Bengali, and ‘the intellect to understand what she was doing’” [6]. Swatilekha Chatterjee (Sengupta) has the maximum screen time in the film among the three main actors. It’s one of the most difficult female roles in Indian cinema which she enacted admirably for a newcomer. To quote Pauline Kael, “Bimala is girlish and coquettish in the early scenes in the women’s quarters, and part of the fascination of the movie is that Swatilekha Chatterjee grows with her role, and becomes more absorbing the longer you see her. She is not a mere ingénue; she’s a full-bodied, rounded beauty, and her Bimala has an earthy, sensual presence” [3]. Unlike in ‘Charulata’ in which the protagonist’s blossoming of a writer alone is hurried though with a montage, ‘Ghare Baire’ brings out Bimala’s character development in all its detail.

‘Ghare Baire’ has some similarities with Ray’s ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’ (1977), based on a Munshi Premchand short story, in that both are based on literary works that cover a period of upheaval in Indian history. ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’ is more in the nature of a historical and the best Indian film in that category. ‘Ghare Baire’ is essentially a love story – however unusual – impacted by a turmoil, the politics of which the film brings out acutely. Like ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’, the period has been captured in great detail in ‘Ghare Baire’ too. The production design by Ashoke Bose recreates the period exquisitely and Soumendu Roy’s cinematography lights up the film with the right ambience. Satyajit Ray started operating the camera himself from 1964 onwards and in ‘Ghare Baire’ too he would have wielded the camera perhaps not fully as he had a heart attack towards the end of making the film. His son Sandip completed it with Ray’s supervision. Those who were critical of the film attributed the “failure” of the film to his illness [6]. On the contrary, the film belies the fact that Ray was unwell as he can be seen touching the pinnacle of his filmmaking in ‘Ghare Baire’ with his screenplay, music and direction – signified by the masterly one-minute sequence of crossing the passage which is pure cinema.

References

[1] “The Home and the World”, Rabindranath Tagore, translated [from Bengali to English] by Surendranath Tagore, London: Macmillan, 1919 [published in India, 1915, 1916]. Link: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/7166/pg7166.html [2] The Script Writer page in the official website of Satyajit Ray. Link: https://satyajitrayworld.org/script_writer.html [3] Pauline Kael’s review of ‘The Home and the World’, New yorker July 1, 1985. Reprinted in her collection of reviews titled “State of the Art”, Published by Plume, 1985, pp 380 -382, ISBN 0-7145-2869-2. [4] Roger Ebert’s review of ‘The Home and the World’, Chicago Sun-Times, January, 1, 1984. Reproduced in the Reviews page of the rogerebert dot com website. Link: https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-home-and-the-world-1984 [5] Vincent Canby’s review of ‘The Home and the World’ in New York Times, June 21, 1985. Link: https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/21/movies/film-by-satyajit-ray.html [6] “Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye”, Andrew Robinson, Published by I. B. Tauris; New edition (21 February 2004), pp 263-273, ISBN-10: 1860649653 [7] The Nation and Its Fragments – Colonial and Postcolonial Histories, Published by Princeton University Press, 1993, p 20, ISBN-10: 0691019436 [8] “The Cinema of Satyajit Ray”, Chidananda Das Gupta, Published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt Ltd., 1980, p 36, ISBN-10: 0706910354

Photo courtesy: National Film Development Corporation (NFDC).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.