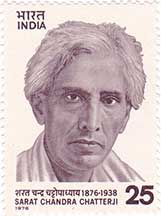

Which author holds the distinction of being the most adapted writer in the cinema of India? Shakespeare? Tagore? Premchand? Or, perhaps, Dharmvir Bharati? We Indians have never demonstrated excessive love for adaptations. Thus, if one were to list the most iconic litterateurs of the subcontinent, it would be noticed that quite a few of them, such as C. Rajagopalachari, Sarojini Naidu, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Suryakant Tripathi, Amitav Ghosh, and Anita Desai have not a single proper film adaptation to their name. There is however [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]one Indian writer whose works have been incessantly adapted, in multiple languages, and across the country — Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay.[/highlight]

IMDB lists 77 titles with Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay credited as writer. It includes films in five languages, spanning 97 years and encompassing filmmakers as diverse as Bimal Roy, Mehul Kumar, Crossbelt Mani, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Anurag Kashyap, Basu Chatterjee, Ajoy Kar, and Adurthi Subba Rao. In fact, in just two years’ time, Sarat Chandra adaptations would have completed a whole century in the film industry.

Sarat himself led a spectacularly fascinating life. During his early days at Bhagalpur, he was so enamoured by the writings of English authors like Charles Dickens, Henry Wood and Marie Corelli, that he himself adopted the pseudonym “St. C. Lara”. Apparently, the St. and C referred to his first name Sarat and middle name Chandra. His mother Bubanmohini Debi passed away when he was only 19. By then, the bug of writing had bit him hard, and he started penning stories in Bengali for local magazines. His father Motilal Chattopadhyay, of extremely humble means, managed to get him a job at the local zamindar’s estate. But Sarat wasn’t at all happy with the work, and following an argument with his father, the former left home.

Sometime later, [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay was discovered in the guise of a sanyasi, standing in the Muzaffarpur office of a popular magazine those days, called Bharatvarsha. In flawless Hindi, he requested to be furnished with writing materials. He was out of pen and paper.[/highlight] He was carrying a notebook, and the pages of that notebook were filled with countless stories. He was shipped back to his hometown.

Around this time, certain accounts mention a lover, a young widow who had captured his imagination. He kept alluding to her in various letters, without explicitly revealing who she was. Apparently, at the behest of this lady love, Sarat sailed for Rangoon in search of a livelihood. According to Radharani Devi, a close confidante of Sarat Chandra and a fiery feminist (back in the early 20th century, she wrote pieces on whether the “dignity” of a woman could be tied to her being a virgin), this mystery woman in Sarat’s live was probably Nirupama Devi, who was widowed as a child and spent a lifetime of rituals and strict rules that were painfully inflicted on Brahmin widows of the time. In his own writings, notably, Charitraheen and Srikanto, Sarat portrayed the state of young widows in Bengal but always fell short of getting them married. It has been hinted that this was because the woman he was in love with never got a chance at such liberation.

Sarat Chandra remained in Rangoon till 1916, and it was during this phase that he got married to Shanti Devi. They were blessed with their first child, a son. But within a year, Shanti Devi and her infant child were claimed by the great plague of 1908. Two years later, Sarat got married again, this time to a widow. They were childless and stayed married till the end of his days. [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]It was after his second marriage that Sarat truly flourished as a literary genius. His new bride, Hironmoyee, was an illiterate but provided the fuel for his creative output.[/highlight] Saratchandra was in his late 30s. In an incredible burst of prolificity, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay produced some of his best works in the next 25 years. Even while in Rangoon, in just the first two years he wrote works like Ramer Shumoti, Bindur Chhele, Naarir Mulyo and Charitraheen. Almost all of these books had formidable women characters, and the male characters seemed to pale in comparison. This remained a hallmark of Sarat’s writing throughout his oeuvre.

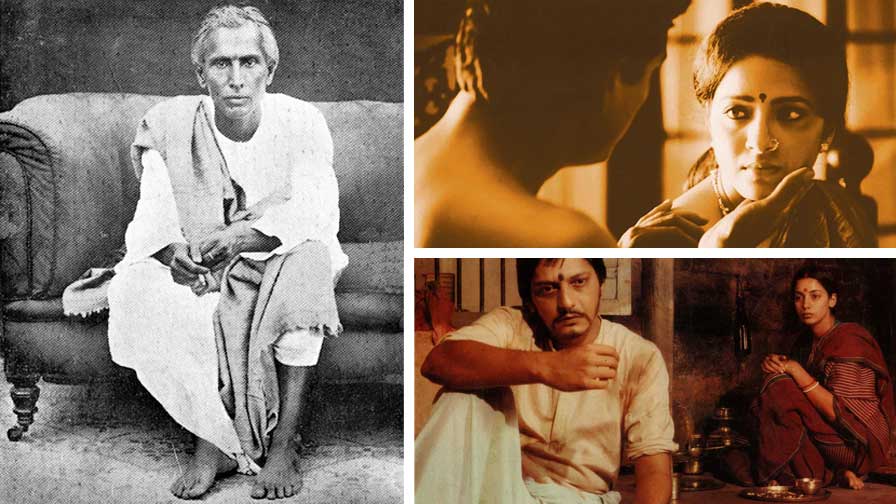

Sarat was back in Bengal and within a few years, the stage adaptations began. It was the golden age of Bengali theatre, and the great theatrical genius Sisir Kumar Bhaduri was prancing about on the stages of Calcutta. Sisir Kumar adapted his story Shoroshi for the theatre and it was a raging hit. Sarat later wrote about it to his soul-sister Radharani Devi, speaking about Sisir in glowing terms. The first film adaptation of his work—Andhare Alo (1922)—was also directed by Sisir Kumar Bhaduri. The silent film was co-directed by Naresh Mitra, who within six years made the first adaptation of Devdas (1928). This was followed by Dhirendranath Ganguly’s adaptation of Charitraheen (1931).

This was the time when a young filmmaker from Assam, Pramathesh Chandra Barua, was experimenting with the new technology of “talkie” films, in Calcutta, and for the first time there was the question of which language to make films in. Barua made the first “talkie” adaptation of Devdas (1935) in Bengali, with him playing the eponymous character. It was an instant sensation. In the following year, Barua directed the Hindi version, with singer-actor Kundan Lal Saigal playing the hero. The Hindi version was an even bigger hit. A Tamil version was made in the year after that. Danseuse and filmmaker Vedantam Raghavaiah made a Telugu/ Tamil bilingual in 1953. It had Telugu superstar Akkineni Nageswara Rao reprising the iconic role. The film became a milestone. Devdas Mukherjee, a jolted, ill-fated lover with a penchant for self-harm, had become the darling of the masses.

This was the time when a young filmmaker from Assam, Pramathesh Chandra Barua, was experimenting with the new technology of “talkie” films, in Calcutta, and for the first time there was the question of which language to make films in. Barua made the first “talkie” adaptation of Devdas (1935) in Bengali, with him playing the eponymous character. It was an instant sensation. In the following year, Barua directed the Hindi version, with singer-actor Kundan Lal Saigal playing the hero. The Hindi version was an even bigger hit. A Tamil version was made in the year after that. Danseuse and filmmaker Vedantam Raghavaiah made a Telugu/ Tamil bilingual in 1953. It had Telugu superstar Akkineni Nageswara Rao reprising the iconic role. The film became a milestone. Devdas Mukherjee, a jolted, ill-fated lover with a penchant for self-harm, had become the darling of the masses.

But Sarat himself did not think too highly of this work. While he was in Rangoon, his friend Pramathanath Bhattacharya tried to coax him into publishing Devdas, which he had written way back in 1901. Sarat responded, “Don’t even think of it. It was written in a drunken state. I am ashamed of the book now. It is immoral…” But Pramathanath convinced him and eventually it was published in the former’s magazine, Bharatvarsha, in 1917.

[highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]It has been more than a hundred years, but Indian cinema’s obsession with the character hasn’t dissipated.[/highlight] The cinematographer of P.C. Barua’s Devdas, a young cameraman called Bimal Roy, adapted his version of the story in 1955. It still remains the most iconic of the lot, and stars Dilip Kumar, Vyjayanthimala and Suchitra Sen. Devdas has been made in Bengali (India and Bangladesh), Telugu, Tamil, Assamese and Malayalam. There was even an Urdu version made in Pakistan, a film that was supposedly a “tribute to Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Bimal Roy and The Great Dilip Kumar”, but the lead actor Nadeem Shah kept aping Shah Rukh Khan, who himself featured in a much-maligned-but-loved adaptation by Sanjay Leela Bhansali in 2002. Even Anurag Kashyap, who, much like Sarat himself, disliked the story, filmed a re-imagination called Dev D in 2009. Bimal Roy’s protege Gulzar planned an adaptation with Dharmendra, Hema Malini and Sharmila Tagore but it never did come to fruition.

Gulzar did however adapt Sarat Chandra’s Pondit Moshai as Khushboo (1975). Basu Chatterjee filmed three adaptations—Swami (1977), Apne Paraye (1980) and Zevar (1987). Bimal Roy directed as many as three adaptations, including Parineeta (1953) and Biraj Bahu (1954). Hrishikesh Mukherjee made Majhli Didi (1950). There were too a number of Telugu superhits starring Akkineni Nageswara Rao, and Tamil films like Manamalai (1958), Maalaiyitta Mangai (1958), and Kaanal Neer (1961).

Sarat Chandra stands tall in the Indian literary pantheon. He wrote only in Bengali, but [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]his translated works are so native to North India that many of his works are considered a part of Hindi literature.[/highlight] Hindi writer Vishnu Prabhakar wrote a biography called Awara Maseeha, which is a veritable classic. Malayali poet Dr. Ottaplakkal Neelakandan Velu Kurup a.k.a. O.N.V. Kurup once said, “Sarat Chandra’s name is cherished as dearly as the names of eminent Malayalam novelists. His name has been a household word.” In a similar vein, his Marathi translations became native to Maharashtra.

Almost all his works are marked by complex and layered female characters and flawed heroes. His almost-autobiographical Srikanto, in its original unedited version, begins with the protagonist writing while in an opium-intoxicated stupor. The portion had to be excised later. Since he showed an upper-class Brahmin widow fall in love in Charitraheen copies of his books were burned in front of his house. His novel Pother Dabi was banned by the British Raj for the depiction of armed revolutionaries.

But while Devdas, admittedly Sarat’s weakest work, has been adapted with great fanfare, [highlight background=”#f79126″ color=”#ffffff”]his magnum opus Srikanto, which displays fascinating glimpses of his personal life and includes some awe-inspiring women, is yet to be adapted in its entirety.[/highlight] Some portions of the latter have been brought to the screen in Bengali, and there was, in the 80s, a television serial featuring Farooq Sheikh as Shrikant. One would think that there is scope for a delightfully complex and layered adaptation of this book, now that we are in the middle of The Great Streaming Wars.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.