When renowned poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz watched Gaman (1978), he was overcome by so many emotions that it was nearly impossible not to say anything about it. He wrote a letter to Muzaffar Ali, the 34 year-old adman who had directed the film. Faiz wrote, “Gaman is a poem in visuals. Its tragic lyricism and muted eloquence is deeply perceptive. It is a sensitively conceived and truthfully captured slice of reality around us, the beauty and the heartbreak of the human situation makes it a sheer delight, a veritable tour de force.”

Mumbai is the Indian version of the American Dream. The proverbial land of opportunities, where thousands converge every year in search of livelihood and a better life. By the mid-19th century, Bombay had become one of India’s most significant ports and trading hubs, which attracted a significant number of migrants from different parts of the world. In 1947, during Independence, more than 50% of Bombay’s population comprised of migrants. For those uprooting themselves from their homes in other states, it represented an erosion of their own societies. In Gaman, Ghulam Hassan (Farooq Sheikh) leaves his wife Khairun (Smita Patil) and his mother back in the village, and lands up in Bombay at the insistence of his friend Lallulal Tiwari (Jalal Agha), who was already pursuing his dreams in the city. The film chronicles the lives of migrants from Lakhimpur Kheri, Muzaffar Ali’s own backyard.

Rajah Muzaffar Ali of the Royal Muslim Rajput family of Kotwara. oocities.org

Muzaffar Ali grew up in the UP township of Lakhimpur Kheri, and the culture of Awadh, along with the age-old tradition of Ganga-Jamuni Tehzeeb deeply fascinated him. While studying at Aligrah Muslim University, this fascination only got deeper and richer. He was influenced by the poetry of revered Urdu poets like Dr. Rahi Masoom Reza, Shahryar, Ali Rahman Azmi, Makhdoom Mohiuddin, and Faiz Ahmed Faiz. These poets at the turn of the century were concerned with a breakdown of what they referred to as “Muaashra”, a construct that is representative of a way of life — the closest English equivalent is ’society’. While consuming their verbiage at an impressionable age, Muzaffar shared their worries about erosion of this way of life. But eventually when his career brought him to the bustling metropolis of Bombay, it was finally clear to him what all this was leading towards. Scores of migrant labourers flocked to the city, disillusioned by rising unemployment in their hometowns. This nudged him in the direction of his first film, Gaman, in which he chronicled the migrant experience. Muzaffar’s Ghulam Hassan finds himself trapped inside the massive belly of the all-encompassing metropolis, finally earning a living but unsure whether he’d be able to leave the city even if he wanted. The City of Dreams had devoured him whole, as evinced by these lines by Shahryar:

Seene mein jalan, aankhon mein toofan sa kyon hai

Iss shahar mein har shaks pareshaan sa kyon hai

Tanhayi ki yeh kaun si manzil hai, rafeekon

Ta-hadd-e-nazar ek bayabaan sa kyon hai

(What is this burning inside the chest…

What is this fire in the eyes…

Why is every person in this city so distressed?

How lonely is this place, friends,

That it’s wilderness as far as the eye can see?)

One film that weaves both his obsessions — poetry and the Awadhi culture — into an elegant bundle of storytelling — is Umrao Jaan, Muzaffar Ali’s magnum opus.

Mirza Hadi Ruswa, a man literally born at the cusp of history, in 1857, produced an abundance of Urdu pulp fiction, had a whirlwind affair with a Frenchwoman named Sophia Augustine, got his heart broken, and carried on amorous adventures with the courtesans of Lucknow. But the man would be known in history for a novel that he insisted was inspired from personal experience, Umrao Jaan Ada. According to Ruswa, an ageing Umrao Jaan herself narrated her life story to him. Sometime in the 70s, Muzaffar Ali, a young advertising executive and budding filmmaker, happened upon the book, which painted a picture of decadence, the last breath of Awadh’s opulence, lyricism and debauchery. Muzaffar recorded the whole book on an audiocassette and listened to it in his car every day. There were moments in the story that he seemed to have experienced in his own life. The resonance was uncanny, and he felt these ‘moments’ could be recreated on film.

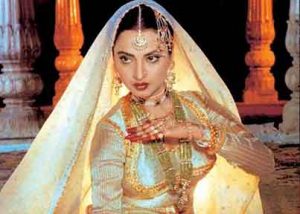

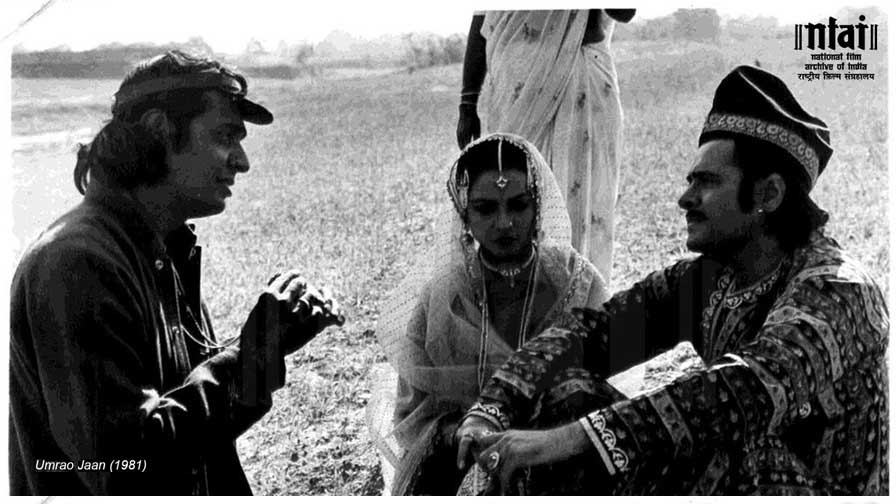

Rekha in Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan

Spotting Rekha — her face and her eyes — on the cover of a magazine, sealed it for Muzaffar that she should be his Umrao. Poet Shahryar was flown in from Aligarh, and Muzaffar Ali hosted him in his own house at Juhu. Music director Khayyam too stayed just around the corner. They sat together for hours, trying to weave the poetry that became the soul of Umrao Jaan. It took them about a year and a half to compose all the songs. Khayyam himself researched extensively on the raagas and singing styles of the 19th century which the courtesans of Lucknow regaled their patrons with. Much like Ghulam Hassan, who had to leave his village to come to an alien Bombay, Amiran is forced to leave her home and end up in a city of boundless exploitation, soul-stirring poetry, exquisite beauty and a promise of love that’s never quite realised. This uprooting was just as painful and Amiran somehow finds it in herself to transform into Umrao Jaan, the queen of a thousand hearts. But unlike Ghulam Hassan from Gaman, she is able to express herself through her art. Shahryar reimagines this soulful quest through the dazzling ghazals encapsulated in the film, with Asha Bhsole breaking form to venture into a domain she had never quite tried before. Rekha completely internalised the alienation, the pain and ultimately the redemption of Umrao Jaan. It had a stellar cast of spectacular actors, all in the prime of their careers: Naseeruddin Shah, Farooq Sheikh, and Raj Babbar. Umrao Jaan swept the National Film Awards and Filmfare Awards announced next year.

After Umrao Jaan, Muzaffar Ali continued exploring themes of alienation and breaking down of communities. Aagaman (1982) is an antithesis to Gaman in the sense that one of its protagonists, Mohan (Suresh Oberoi), comes back to the village after being educated in the city, and tries to unite sugarcane farmers so their exploitation by the mill-owners can stop. The film introduced a talented young actor by the name of Anupam Kher, who played Mohan’s father Ramprasad. With Anjuman (1986), Muzaffar Ali went back to old Lucknow and the erosion of old-world values. And like migrants in Gaman, courtesans in Umrao Jaan, sugarcane farmers in Aagaman, Muzaffar Ali adopted the milieu of chikankaari artisans of Lucknow.

In the 80s, many trips to Kashmir endeared Muzaffar to the concept of Sufism and Sufi philosophy. Intrigued by the enigmatic Kashmiri poetess from the 17th century called Habba Khatun, he mounted his dream project Zooni on an epic scale. Dimple Kapadia was cast in the titular role, and Vinod Khanna in a role opposite her. Dimple and Vinod had just returned from their respective sabbaticals and their casting caused plenty of media attention. But Muzaffar’s lofty vision for the film, his perfectionism, insurgency in Kashmir, lackadaisical attitude of the government and similar logistical challenges kept stalling the project. Muzaffar Ali kept trying to revive the film till as late as 1997, but to no avail. His dream remains unfulfilled, much like his muse Umrao Jaan Ada, who lamented,

Justajoo jiski thhi, usko toh na paaya humne

Iss bahaane se magar dekh li duniya humne

Tujhko ruswa na kiya, khud bhi pashemaan na huye

Ishq ki rasm ko iss tarha nibhaaya humne

(I could not get the one I coveted

But I did find what the world was all about

I neither dishonoured you, nor shamed myself

And thus did I fulfil the demands of Love)

Dear Amborish

Very eloquently written !