I know that you are no more.

But I am, alive for you

Believe me.

When the seventh seal is opened

I will use my camera as my gun

and I am sure the echo of the sound

will reverberate in your bones,

and feed back to me for my inspiration.

– John Abraham about Ritwik Ghatak

John Abraham and Ritwik Ghatak. That combination sounds blasphemous already. But it shouldn’t. Because the John I am talking about blazed a trail through Indian cinema that nobody since has had the gall to follow. This is how Jacob Levich distinguished Ghatak from Ray: “Satyajit Ray is the suitable boy of Indian film, presentable, career-oriented, and reliably tasteful. Ghatak, by contrast, is an undesirable guest: he lacks respect, has “views”, makes a mess, disdains decorum” Pick up those colourful words used for Ghatak, and use them on John Abraham. Every word fits with equal resonance.

John Abraham was the Enfant terrible of Malayalam cinema. His work, like his mentor’s, was marked with a blatant disregard for established mores, while displaying a longing for days gone by. The rebellious streak was a constant in him, till the day he breathed his last. Even during his FTII days, John had been suspended from the hallowed halls of the institute. Not once, not twice, but four times. And yet he graduated with a gold medal in direction and screenwriting. This contrast permeated through his as well as his mentor Ritwik Ghatak’s life.

Ritwik Ghatak joined FTII in the year 1965. He had already made six of his most acclaimed films, had had a brief and rather unsavoury brush with what we know as Bollywood today. It was Ritwik’s brother, Sudhish Ghatak, who had wielded the camera for the venerable Phani Majumdar’s Street Singer, was responsible for Bimal Roy getting into New Theatres Studios as a camera assistant, back in the 1930s. Later Ritwik started his stint in filmdom by assisting him in Roy’s early works like Tathapi, where Ghatak was chief assistant. After Ritwik got married to his wife Surama Ghatak, a fiery revolutionary an active IPTA member, he was looking for stability by way of gainful employment and landed up in Bombay, working for Bimal Roy Productions. Ghatak wrote Bimal Roy’s classic Madhumati as well as Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s debut venture, Musafir. But despite the box office success of these films (or maybe, because of it) he was disillusioned and left the glitter of Bombay behind and returned to the grime of Calcutta. Back to the bottle, back to the endless Sunday sessions at Coffee House with the likes of Utpal Dutta, Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha. Meghe Dhaka Tara brought in acclaim and recognition, but Komol Gandhar floundered at the box office.

Ghatak household was mired in financial insecurity. Ritwik and Surama were facing a bad patch in their conjugal life, and were living separately. The fact that he admitted to her of falling love with another woman, wasn’t helping. Ritwik’s life is like a series of self-destructive indulgences, punctuated by short bursts of lucidity, something which us lesser mortals will perceive as “normalcy”. During one of these phases, Ghatak decided to make things up with Surama and obtain a secured employment. That is when he took up the teaching job at FTII. There are fables about Ritwik Ghatak at the institute. One of them is about him dishing profound philosophy on life and cinema in a state of drunken stupor, to his disciples sitting under the Wisdom Tree. There were the likes of Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Subhash Ghai. And then there was John.

Ghai and Chopra never tired of speaking about the master and his influence on their lives. Ghai says he was the one helping Ghatak to his room after the drinking binges. Chopra tells stories of how Ritwik rambled to him in Bengali, and eventually suggested the moniker “Vidhu”, permanently added to his name. Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani built their own oeuvre, with a distinct world view. But it was John Abraham from Kerala who ultimately carried the mantle of Ritwik Ghatak. If Ghatak had a cinematic heir, it would without a doubt be John.

John Abraham wasn’t just a wide-eyed youngster who crowded into Pune Film Institute (as FTII was referred to back then) merely to make a career in the movies. He was barely 12 years younger to Ghatak, and was well in his mid-30s by the time he graduated. John was kind of wandering across disparate career opportunities when he chose to abandon everything and enrol for film school. He had been teaching in college, and worked briefly for Life Insurance Corporation as well. Which means this move must have been well thought out and extremely risky at the same time. John’s IMDB lists three diploma films he was associated with: Koyna Nagar, Priya and Hides and Strings. This is not unusual. Students have been known to work in others’ diploma films even after they had graduated. Also, Ritwik made some changes in the curriculum of the institute to emphasise on practice rather than theory.

Not only Ritwik’s pedagogy, but his politics, worldview and philosophy had a great impact on John Abraham. And John was primed for it, having had his formal education in politics and history from the Mar Thoma College at Thiruvalla. Both Ritwik and John were short story writers. And just like his mentor, John had a brief brush with Bollywood. He assisted on a Waheeda Rehman starrer called Trisandhya but unlike Ghatak, John’s film probably never saw the light of the day. But in 1969, he would get the opportunity to work on another Hindi film, Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti – which pretty much set the stage for ‘Parallel Cinema’ in India. John not only assisted his friend, but also appeared in a minor role.

John Abraham’s directorial debut was a rather conventional and tame Vidyarthikale Ithile Ithile, featuring mainstream Malayalam movie stars like Madhu aka Madhavan Nair and Jayabharathi. It was with his second film that he truly came into his own.

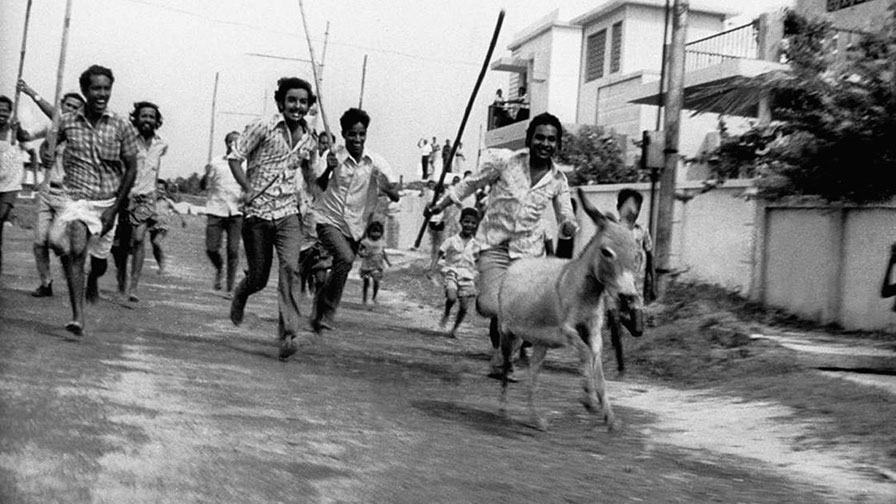

Agraharathil Kazhutai is about an ill-fated donkey that finds himself in a neighbourhood dominated by chaste Brahmins. Though initially some kind souls treat the beast with some affection, he faces bullying for the most part (among others, at the hands of some students who draw Nietzsche-in parallels with the “Ass”). Eventually, scared of the ill-luck brought about by the animal, the donkey is killed off by the residents. Displaying John’s almost-brutal capacity of pitch-dark humour, the donkey’s murder unleashes death and destruction in the Brahminical village. And then, miracles start manifesting themselves.

John was even more Ritwik than Ritwik, in some ways. Barring a couple of documentaries, Ghatak didn’t do any work outside of Bengali, the language and milieu he was most comfortable with. John’s breakout film Agraharathil Kazhutai was a Tamil film, though he primarily identified as a Malayali filmmaker. The film created waves. Earned a National Award, among other things. John Abraham also innovated an early example of crowdfunding in cinema. He launched the Odessa Collective in 1984, which went around campuses, small towns and villages in Kerala, staging street plays and screening old films, collecting money from people who volunteered to pay for the experience. The resultant money was utilised towards production and distribution of tightly budgeted indie films. One of them was Amma Ariyan, which has become the other definitive John Abraham film. Amma Ariyan, literally meaning a letter to mother, is about a man traveling with the dead body of a stranger, trying to take him to his mother. The lead was played by Joy Matthew who in 2012 created waves with his Malayalam film Shutter, inspiring remakes in Tamil, Telugu, Punjabi, Tulu and Marathi.

John’s persona, much like his master, attained mythical status. His quirk, his spontaneous refusal to comply, an outrageously self-destructive streak, all of this added to the allure, perhaps. Anecdotes abound to establish this. Amma Ariyan was being screened at the Flaiano film festival and John was waiting for his flight to Italy. His partners in crime, when they reached the airport, noticed John had forgotten his shoes. He right there, standing barefoot, waiting for his flight to Italy! Similarly, on another occasion, he took off his pants and gifted them to a rickshaw driver when the man complimented him on his jeans.

A 50-year-old Ritwik Ghatak died, derelict, consumed by the bottle and in the mouth of madness. Little more than a decade later, on 31 May 1987, John Abraham fell from the terrace during a party. He had been drinking copiously. He died a day later, two months short of his 50th birthday.

“I have lived on the lip

of insanity, wanting to know reasons,

knocking on a door. It opens.

I’ve been knocking from the inside.”

– Rumi

[divider text=”Go to TOP” size=”1″ margin=”0″]

IMDB link of John Abraham

[youtube_advanced url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NJHrYokoE1A” width” width=”300″ height=”200″ responsive=”no” controls=”alt” autoplay=”yes”]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.