There are film directors who create film stars and then there are film directors who become stars themselves.

Since cinema started as a means of business, stars and star film directors have both co existed. A star could not survive without a good film director but a star film director could thrive without stars. Each national language cinema has had its fair share of both stars and star film directors. In India, individuals in both categories have lived and thrived by the dozens; while in countries with smaller film audiences, star directors have been few. Miklós Janscó was one such rare star among directors.

Hungary after the Second World War produced one of its greatest film directors in Janscó, whose rise to fame and a career in cinema within his country was gradual and partly unnoticed. His first achievement with reference to the political scenario was that he survived the Big War. His second achievement was that he could pursue his passion for films starting from a still camera and moving to a movie camera to record the process of reconstruction of his country while making short documentaries. His third achievement was that he came to the notice of his authoritarian masters. His ultimate such achievement was that he survived his authoritarian masters and made anti establishment statements through his films.

In a cinematic career spanning the years between 1954 and 2010, Janscó made 33 feature films, 19 documentary films and 28 newsreel topicals. Considering that the Hungarian film industry was destroyed by the occupation armies of Germany and was later resurrected by the Soviet administration, his total work output is truly impressive.

Janscó came to be introduced to Indian audiences with his feature film The Round-Up, aka The Outlaws. The opening up of Hungarian cinema to Indian audiences occurred under rather strange circumstances. It happened towards the end of 1970 when a Hungarian anthropologist Geza Benphalve arrived in New Delhi with a package of films from his nation, and sought help to show them to the local audiences. Two decades later, he returned to New Delhi to be the Director of the Hungarian Cultural Centre. In his second outing he did not emphasize the fact that it was he who had introduced Hungarian cinema in India starting with the screening of Janscó’s The Round-Up. This film, it is important to add, had previously—in 1971 to be precise—been screened in India by the Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI), but it was only during its reintroduction by Benphalve in the end-70s that it made its impact on Indian festival audiences.

Today, Janscó is a person lost in time both in Hungary and in India. The rights of his films are controlled by the Hungarian National Film Fund, and they charge a royalty of around USD 3500 per show. Since he is not “entertainment,” no one wishes to pay to see his films, and so his films are not looked forward to. In India, more than a decade ago, FFSI had paid for the royalties and shown his films as a special retro, on request from the Hungarian Cultural Centre. The introduction that I had written was circulated along with Janscó’s films in the festival circuit. His films were received coldly at that time by 95 percent of the audiences here, and no one else was interested in writing on them. Furthermore, the leaders in the Directorate of Film Festival had not even heard of him. Hopefully, this write up will spark an interest among Indian festival directors to host a Janscó retrospective package. Presently, the number of people in India who have seen his films can be counted on one’s fingers.

Janscó never did visit India. And a glance at the record books shows that India has received a far less number of his works than even that of his second wife Marta Mazarous. In fact, she was offered two retrospective packages in India while Janscó wasn’t afforded a single one in India in his entire lifetime. Mazarous served twice on the International Film Festival of India jury—the first time, as a regular member, and the second as the chairperson. Merit-wise, Mazarous acquired more national and international fame than Janscó, but it was on Janscó’s limited works and not Marta extensive works that film critics wrote extensively. Furthermore, Janscó’s The Round Up was reportedly seen by one tenth of the total population of his country, a rare feat by any standard, and it was the first hit film in post-WWII Hungary.

Janscó is best remembered for a unique signature in film narrative that was marked by the sparing use of words in dialogues interspersed by long scene takes. In Red Psalms, this style took an extreme position when scenes were allowed to linger on for 9 minutes and more without a single cut. Film critics found in such depiction, symbolism that perhaps even the film director never thought of. But he accepted these interpretations since they created for him a distinct image that added to his cinematic aura in the international film circles.

Miklós Jansco’s worldwide fame remained, till his demise in early 2014, with a fan following that aged along with him. Even in his old age, despite suffering from cancer, the film director was still at work. His last film So Much For Justice was made in 2010 when he was all of 90 years of age.

[divider size=”1″ margin=”0″]

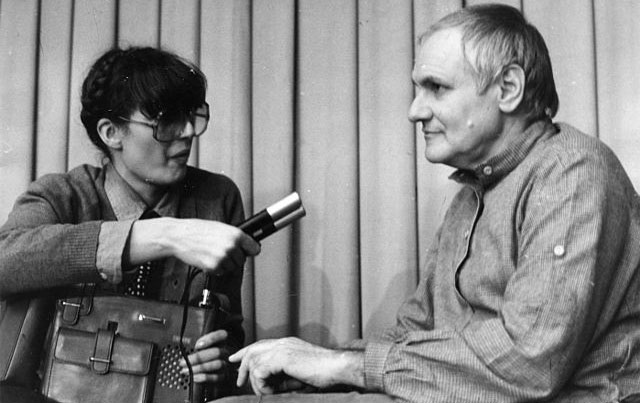

Photo credit: Fortepan adományozó RÁDIÓ ÉS TELEVÍZIÓ ÚJSÁG / VERESS JENŐ felvétele. Jancsó Miklós interjút ad a Magyar Rádión munkatársának | CC-BY-SA-3.0

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.