Indian OTT Cinema is the ‘Third Big Bang’ in History of Indian Cinema: A Comparative Analysis of OTT Hindi Cinema versus Hindi Cinema Tradition

Abstract:

Watching films like The Archies (Akhter, 2023), Kho Gaye Hum Kahan (Singh, 2023) and Jane Jaan (Ghosh, 2023) makes one realize that these are not mainstream Bollywood films or what have been called masala[1] films. Hindi cinema officially started by Phalke’s desi[2] cinema has a long and commendable tradition of films starting with mythological genre, to studio cinema, star cinema, the golden age of melancholy and socialism and the socials and the angry young man era to the romance and action films of 1980s and the domestic dramas of 1990s to hatke[3] films of the 2000s and the digital invasion of 2010s and it goes on. It also has divergent traditions of parallel and new wave and the hatke films but exclusive OTT films are different. Not only are the films unconventional in storyline, character portrayal and basic narratives but the platforms that they are released on and the kind of reception they receive is also contrasting compared to the mainstream cinema. This research paper would look at the inception of exclusive OTT cinema[4] in India, the reasons behind it – survival of the film industry during Covid times, technological changes, medium characteristics, niche audiences and freedom to experiment with storytelling. It would also look at the text of this cinema and compare it with the text of a typical masala film to understand how the cinema has evolved into new spaces in India.

Keywords: Hindi Cinema, OTT Cinema, Audiences, Masala Film, Film Business

Introduction

Shah Rukh Khan made a blockbuster comeback in 2023 with films like Jawan (Kumar, 2023) and Pathaan (Anand, 2023). These films garnered massive fanfare, strong recall value, and substantial box office profits. They are considered tentpole comeback films for SRK. Collectively, his three releases in 2023—Jawan, Pathaan, and Dunki (Hirani, 2023)—grossed approximately ₹2500 crore worldwide, reaffirming his position as a frontrunner in the box office race (Madhukalya, 2023). In contrast, films like Jaane Jaan (Ghosh, 2023), starring Kareena Kapoor Khan, Vijay Varma, and Jaideep Ahlawat, and Kho Gaye Hum Kahan (Singh, 2023), produced by Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti, were released directly on OTT platforms. These films represent a different kind of cinema—niche, modest in budget, and intended for a more specific audience.

Indian cinema encompasses various subcategories, with Hindi cinema being the most prominent, and Indian OTT cinema emerging as a significant new category. Hindi cinema has a well-established tradition characterized by genre fluidity, digressions, narratives rooted in mythology and folklore, star-driven appeal, strong industry verisimilitude, and a loyal audience base (Thomas, 1985). In comparison, Indian OTT cinema is still carving out its identity. It is fresh, unconventional, and often breaks away from the established norms of mainstream cinema, whether in terms of content strategy or financial expectations.This research paper critically examines the longstanding tradition of Hindi cinema while exploring the emergence of OTT cinema in India. It investigates the factors that contributed to the development of OTT films as a distinct category, including an analysis of their textual and narrative features in comparison to mainstream Hindi cinema. In addition to secondary research, which outlines the two filmmaking traditions—Hindi cinema and Indian OTT cinema—the paper also presents a comparative textual analysis between Jawan, a typical Bollywood masala film, and Kho Gaye Hum Kahan, a representative exclusive OTT release.

Literature review

i. A historical context to Indian Popular Cinema

Hindi cinema, post 1990s also known as Bollywood, has a rich and diverse history that spans over a century. The foundations of Indian cinema were laid in the early 20th century with the release of the first Indian feature film, Raja Harishchandra (Phalke, 1913). Silent films dominated this era, and filmmakers like Himanshu Rai and Franz Osten formed the Bombay Talkies in the 1930s. The 1940s saw the emergence of iconic filmmakers like Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, and Bimal Roy, contributing to the Golden Age of Indian cinema. Classic films such as Awara (Kapoor, 1951), Pyaasa (Dutt, 1957), and Mother India (Khan, 1957) were produced during this period. The industry also witnessed the rise of playback singers like Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi. The 1970s marked a shift towards masala films, characterized by a mix of action, drama, romance, and musical numbers. Amitabh Bachchan emerged as a megastar, starring in blockbuster films like Sholay (Sippy, 1975) and Deewar (Chopra, 1975). The era also saw the rise of the angry young man [7] archetype in Bollywood.

Filmmakers like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, and Satyajit Ray explored realistic and socially relevant themes in their films, giving rise to parallel cinema[8]. Arth (Bhatt, 1982) and Mirch Masala (Mehta, 1987) are examples of films that diverged from mainstream commercial cinema. The 1990s marked a revival of romance in Indian cinema, highlighted by the success of films such as Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (Chopra, 1995) and Hum Aapke Hain Koun (Barjatya, 1994). This era also witnessed the rise of stars like Shah Rukh Khan, Aamir Khan, and Salman Khan, who went on to become influential personalities in the Bollywood industry. The industry expanded its reach, with Indian films being screened at international film festivals and gaining a global audience. Technological advancements and increased collaborations with foreign filmmakers have further propelled the globalization of Hindi cinema. The 2010s saw a diversification of themes and storytelling styles, with films like Queen (Bahl, 2013), Dangal (Tiwari, 2016), and Gully Boy (Akhtar, 2019) breaking traditional norms. Content-driven cinema gained popularity, and filmmakers began to address social issues with a fresh perspective. (Ganti, 2013; Dwyer, 2014; Rajadhakshya, 2016)

ii. Critical thoughts on Hindi cinema

Prasad (2000) extensively analyzes the cultural and political dimensions inherent in popular Indian films, offering a unique perspective on Indian cinema. His focus encompasses the economic, narrative, and institutional aspects, unveiling the intricate relationship between cinema and society within a post-colonial context. According to Prasad, the Indian film industry grappled with asserting its entitlement to state support, bank loans, and legitimate investment. He underscores the dominance of the distribution sector in financing, resulting in a formal rather than genuine integration of production with capital. This fragmentation impacted the diverse components of production, influencing the specific skills and narrative elements involved in filmmaking. Prasad discusses the characteristic narrative structure of popular Indian films, emphasizing the performative expression of familiar story elements, moral imperatives, and rhetorical modes of character speech. His exploration probes how these narrative elements are shaped by the cultural and historical context, reflecting the intricacies of Indian society and politics.

Mishra (2013) investigates into the historical, cultural, and social dimensions of Bollywood, providing insights into its growth, impact, and significance as a cultural phenomenon. He evaluates Bollywood’s evolution, narrates its journey, and scrutinizes the ideological and aesthetic elements that contribute to its enduring popularity. Bollywood emerged in the early 20th century as a response to colonialism and the Indian struggle for independence. Inspired by Indian folk traditions and Western cinema, Bollywood created a unique blend of cultural influences. The introduction of sound in the 1930s revolutionized Bollywood, contributing to its rapid growth. Bollywood films are known for their extravagant song and dance sequences, elaborate costumes, and grand sets. Emotional storytelling, larger-than-life characters, and the celebration of love and family are central to Bollywood narratives. Bollywood often addresses social issues such as poverty, gender inequality, and communal harmony. The rise of Bollywood stars and their fan following played a significant role in shaping the industry. Bollywood films have gained global popularity, serving as cultural ambassadors and offering insights into Indian traditions and modernity.

Bollywood often perpetuates traditional gender roles, portraying women as objects of desire. Some films feature female protagonists challenging societal norms and asserting independence. Male sexuality in Bollywood is often veiled and expressed through symbolism. Bollywood reflects and shapes political ideologies, both nationalist and global. Films have been used for sociopolitical messaging. Bollywood plays a crucial role in constructing and maintaining national identity through its representation of religion, particularly Hinduism. Bollywood’s commercial success heavily relies on the Indian domestic market, making it a global film industry leader. The distribution system, star power, and the rise of multiplexes have shaped Bollywood’s economic structure. Bollywood shapes consumer culture through film-related merchandise and endorsements. (Malhotra & Alagh, 2004; Dwyer, 2015; Ganti, 2014; Rajadhakshya, 2015)

Vasudevan (2000, 2014) delineates cinema’s multifaceted impact on the cultural, social, and political landscape of the country. He discusses the historical, aesthetic, and narrative dimensions of Indian cinema, offering valuable insights into its distinct characteristics and importance. Indian cinema, with its diverse languages, cultures, and regional industries, mirrors the vast diversity of the nation, providing a platform for a myriad of stories, experiences, and perspectives. It has evolved into a potent medium for filmmakers to address social, political, and cultural issues prevalent in the country, serving as a powerful tool for collective consciousness and social commentary. He underlines the pivotal role of the audience in shaping the meaning and reception of Indian cinema, analyzing the dynamic relationship between filmmakers, films, and viewers, with a focus on context and interpretation. Globalization has significantly influenced Indian cinema, introducing new narrative styles, themes, and visual aesthetics, impacting not only content and distribution but also prompting critical reflections on authenticity and cultural appropriation. The portrayal of gender in Indian cinema undergoes scrutiny, with an examination of evolving representations of women on screen and a critical stance on prevailing stereotypes, shedding light on feminist voices and movements within the industry. Regional film industries, including Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, and Malayalam cinema, are thoroughly examined, emphasizing their unique contributions to the broader landscape. His work dives into the diversity inherent in the Indian film industry, highlighting the significant role of regional cinema in shaping the cultural narrative. The incorporation of music and dance in Indian cinema, emphasizing their integral position in storytelling and popular culture, is discussed, recognizing their contribution to the emotional and aesthetic appeal of the medium.

India, as the leading global producer of feature films, exemplifies the profound impact of cinema on its societal fabric. The communal nature of movie-watching in the country involves diverse participants, creating a vibrant experience. Even when attending alone, male viewers often contribute to a shared experience through vocal responses like shouting and engagement with the screen. Audience engagement in Indian cinema halls goes beyond passive observation, with attendees actively participating through sound effects, reciting dialogues, and offering commentary, becoming integral to the unfolding narrative. The cultural tradition of repeat viewing, rooted in Hindu practices, contrasts with the more individualized perception of film-viewing in the United States. Indian movie marketing acknowledges various ‘extras’, recognizing the social nature of movie-going. These findings highlight the distinctive social, cultural, and participatory aspects of the cinematic experience in India, setting it apart from Western movie cultures. Banaji’s research on young people’s interaction with Hindi films adds nuanced insights into varied interpretations of film narratives, challenging stereotypes and showcasing the multifaceted nature of the film-viewing experience. (Srinivas, 2002; Banaji, 2006).

Content recreated and trans-created from traditional Indian epics, such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, often inspires characters and plots in commercial Hindi cinema. The emotional content presented aligns with aesthetic theories found in Indian epic narrative. The stereotyping of characters and relationships in Hindi cinema shows influence from Indian epic structure. The self-reflexive humor in Hindi cinema is inspired from the historically powerful traditions of Indian drama and narrative. These findings accentuate the deep-rooted influence of traditional Indian culture and storytelling on the content and narrative structure of commercial Hindi cinema. This critical analysis of realism and emotion in films provides valuable insights into the societal and cultural implications of cinematic representations. The inclusion of diverse perspectives, such as psychoanalytic, cultural studies, and cognitive science models, enriches the discourse on Hindi cinema, showcasing multifaceted approaches to understanding its significance. The emphasis on audience activity and the distinctiveness of Hindi films adds depth to the exploration of this cinematic genre (Booth, 1995; Roy 2017, Hogan, 2009).

iii. The world of OTT

In recent years, the landscape of cinema has undergone a transformative shift, with the rise of Over-The-Top (OTT) platforms redefining the way audiences experience and consume films. The phenomenon of exclusive releases on OTT platforms has emerged as a game-changer, providing filmmakers with new avenues for creative expression and audiences with unprecedented access to diverse cinematic content. One of the key advantages of exclusive OTT releases lies in the accessibility it offers to viewers worldwide. Unlike traditional theatrical releases limited by geographical constraints, OTT platforms allow films to reach a global audience instantaneously. This democratization of access has paved the way for filmmakers from various corners of the world to showcase their work without the traditional barriers of distribution. Moreover, the exclusive release model on OTT platforms has given filmmakers the flexibility to experiment with unconventional storytelling techniques and genres. Freed from the constraints of box office expectations and runtime limitations, creators can dive into complex narratives, niche subjects, and experimental forms of filmmaking that might have struggled to find a place in mainstream cinemas. OTT platforms have also become a haven for independent filmmakers and emerging talents. With the conventional studio system often favoring big-budget productions, OTT platforms offer a level playing field, allowing smaller-scale, and innovative films to find their audience. This democratization of the film industry has nurtured a diverse range of voices and perspectives, enriching the cinematic landscape with fresh and compelling storytelling. (Khandekar, 2021; FICCI FRAMES 2023 ; Partho Dasgupta – Change in the Strategy of OTT Platforms Needed to Succeed in India, 2022; Netflix’s Monika Shergill on Understanding Audiences, Stories and the Storytelling Journey, 2021)

The streaming environment has also sparked a renaissance in episodic storytelling. Exclusive OTT releases often come in the form of series or limited episodes, providing filmmakers with a longer canvas to develop characters and intricate plotlines. This format not only caters to binge-watching trends but also allows for a more immersive and detailed exploration of narratives, creating a unique viewing experience that contrasts with the traditional two-hour film format. However, the rise of exclusive OTT releases has not been without its challenges. The theatrical experience, cherished by many cinephiles, is undergoing a shift, prompting discussions about the future coexistence of traditional cinemas and digital platforms. Filmmakers now face the choice of whether to pursue a traditional theatrical release, an exclusive OTT launch, or a hybrid model that combines both. (Drennan & Baranovsky, 2018).

OTT stands for ‘Over-The-Top’, and it refers to a type of media distribution that bypasses traditional cable, satellite, or broadcast television platforms. In the context of the entertainment industry, an OTT service typically delivers content (such as movies, TV shows, and other video content) directly to viewers over the internet. Instead of relying on traditional methods of distribution, like cable or satellite television, OTT services make use of the internet to reach their audience. OTT platforms are known for providing on-demand content, allowing users to stream videos whenever they want, as opposed to scheduled programming. Commonly known OTT services encompass Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime Video, Disney+, and various additional platforms. These platforms have become increasingly popular as technology has advanced, providing viewers with more flexibility and control over their entertainment choices. OTT platforms have democratized access to content, making it available to a global audience. Viewers can access movies, TV shows, and other content from anywhere with an internet connection, breaking down geographical barriers (Partho Dasgupta – Change in the Strategy of OTT Platforms Needed to Succeed in India, 2022; FICCI FRAMES, 2023).

OTT services have given rise to a diverse range of content, including films and series that might not have found a place in traditional mainstream media. Niche genres, experimental storytelling, and independent productions have flourished on these platforms, catering to a wide array of tastes and preferences. Filmmakers and content creators benefit from the creative freedom provided by OTT platforms. They can explore unique and unconventional storytelling without the constraints often imposed by traditional studio systems. This has led to a surge in original and innovative content. OTT platforms have popularized the binge-watching culture, where viewers can consume multiple episodes or an entire season of a show in one sitting. This has changed the way narratives are crafted, allowing for more intricate and serialized storytelling.

The rise of OTT platforms has disrupted traditional distribution models. Filmmakers now have the option to release content exclusively on streaming services, challenging the dominance of theatrical releases. This has led to discussions about the coexistence of traditional cinemas and digital platforms. OTT platforms leverage user data to personalize recommendations, tailoring content suggestions based on individual viewing habits. This data-driven approach enhances user experience and helps platforms retain and engage their audience. Some filmmakers and studios are adopting hybrid release models, combining theatrical releases with simultaneous streaming on OTT platforms. This allows for greater flexibility and a broader reach, appealing to both traditional cinema-goers and digital audiences. OTT platforms invest heavily in producing original content to differentiate themselves in a competitive market. This has led to high-quality productions, attracting top talent in the industry and further diversifying the content available to viewers. OTT platforms employ various monetization strategies, including subscription-based models, ad-supported content, and a combination of both. This flexibility in revenue models has contributed to the sustainability and profitability of these platforms.

Evaluating various streaming entertainment platforms in the Indian market involves considering several key parameters such as regional content, pricing strategy, licenses, telecom tie-ups, and technological innovations. The increasing demand for internet connectivity, coupled with upcoming mobile networks offering unlimited data, is making online streaming services more accessible and affordable in India. The availability of 4G and LTE networks further contributes to the growth of online streaming services. Brands like Amazon Prime Video and Netflix have gained popularity in the Indian market due to factors like localized regional content, ease of accessibility, and affordable pricing. Focusing on regional content is identified as a key strategy for unlocking the digital market in India, given the lower viewership of English programs (Moochala, 2018).

The paper ‘Cinema viewing in the time of OTT’ reports findings from a survey and semi-structured interviews among viewers of OTT platforms. Nearly 89% of respondents prefer watching films on OTT platforms like Amazon Prime Video, Hotstar, Netflix, and Zee5. The majority of respondents fall in the 18 to 25 age bracket, with a significant female representation. The study suggests a shift in audience preference from big screens to small screens, particularly among the 18-35 age group. Despite the trend toward private viewing, audiences engage with peers through virtual social media spaces to discuss content, connecting to a larger global communication network (Chatterjee and Pal, 2020). The factors contributing to the rising adoption of OTT video services in India include increasing internet and broadband penetration, declining data charges, proliferation of internet-enabled mobile phones, and personalization of content, and competitive pricing. The streaming market collectively accounted for 46% of the overall growth in the Indian entertainment and media industry from 2017 to 2022. Local services like Hotstar and Jio Cinema, along with global platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime, have gained traction in the Indian market. The pandemic accelerated the adoption of OTT platforms due to ease of access, content variety, and limited entertainment options during lockdowns. The potential challenges for OTT services in India include their impact on traditional services, regulatory concerns, and market power issues (Nijhawan & Dahiya, 2020).

India, being the second-largest market for tech companies globally, has witnessed rapid growth in OTT video services. Factors driving this growth include digital infrastructure development, price wars associated with the rollout of 4G, and increased smartphone penetration. State policy and regulation, including the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India’s (TRAI) consultation on the regulatory framework for OTT services, play a significant role in shaping the industry (Fitzgerald, 2019).

The convergence of cinema and social media is evident in contemporary discussions, as highlighted in Madhusree Dutta’s documentary 7 Islands and a Metro (2006), where marginalized individuals actively shape their representation through social media. Ethical considerations in cinema are explored by Elora Halim Chowdhury in Ethical Encounters (2022), focusing on the aftermath of the Bangladesh Liberation War. Lalitha Gopalan’s work, Cinemas Dark and Slow in Digital India (2021), examines the evolving aesthetics of digital independent films in cities like Delhi, Bangalore, and Chennai. Eda Kandiyil Ahmad Faseeh’s fieldwork on Deccani cinema explores the negotiation of Muslim identity within film production practices in Hyderabad. Amrita Chakravarty’s research article addresses the archiving of cinematic gestures and phrases in the era of new digital media, emphasizing the transition of Hindi cinema’s filmi culture to digital platforms (Vasudevan et al., 2023)

Research Objectives:

1. To understand Indian OTT cinema as the ‘Third Big Bang’[9] moment in Indian cinema.

2. To compare the traditions of mainstream Hindi film and the newly erupted OTT Hindi cinema.

3. To observe the industry verisimilitude, text of Indian OTT cinema and reception of Indian OTT films.

Research Methodology

This is a qualitative study where the traditions that are followed by Hindi cinema and are being created by evolving OTT cinema in India are being discussed in the literature review section. Here the researcher has taken a purposive sample of two films based on convenience and critical review of both the films which places them in contemporary traditions of Indian cinema. Two film theories Genre film theory and Rasa theory are being used to critique these two films respectively. Genre theory emphasizes on the narratives, iconography and ideology of films in a particular genre and that is what has been discussed in the films’ textual analysis which is taken from the OTT universe as a sample for discussion- Kho Gaye Hum Kahan. Also Jawan another film which has been taken as a sample to represent tent-pole masala films of Indian cinema is critiqued through the rasa theory lens because genre theory doesn’t apply to the traditions of typical masala film which has multiple plots, song and dance sequences, stereotypical and exaggerated character performances, a predictable conventional storyline infused with elements of melodrama.

Genre theory is a concept within the field of literary and film studies that focuses on categorizing and analyzing works of art based on shared characteristics, themes, and conventions. It helps scholars, critics, and audiences understand and interpret different types of media by identifying patterns and expectations associated with specific genres. A genre is a category or type of artistic composition characterized by a particular form, style, or content. Genres can be applied to various forms of art, such as literature, film, music, and visual arts. Each genre has its own set of conventions, which are the typical features and elements associated with that genre. These may include narrative structures, themes, character types, settings, and stylistic choices. Audiences often have certain expectations when engaging with a particular genre. For example, viewers expect horror films to evoke fear, romance novels to explore romantic relationships, and science fiction stories to involve futuristic elements. Genres serve specific functions and purposes, both for creators and audiences. They provide a framework that allows creators to communicate with their audience effectively, and they help audiences make sense of and interpret the work. Some works may blend elements from multiple genres, creating hybrid genres. These works challenge traditional genre boundaries and offer new and innovative ways to express artistic ideas. Genres are not static; they evolve over time in response to cultural, social, and artistic changes. New sub-genres may emerge, or existing genres may undergo transformation and adaptation. Genres often reflect the cultural and societal values, concerns, and anxieties of a particular time and place. They can be used to explore and comment on social issues, norms, and attitudes.

Genre theory provides a framework for critical analysis and interpretation of works within a specific genre. Scholars and critics use this framework to examine how a work adheres to or deviates from genre conventions, as well as to explore the cultural and thematic implications of the work. Genre theory is a tool that helps us understand, classify, and analyze works of art by identifying patterns and conventions within specific categories. It provides a shared language for discussing and interpreting creative works across various media (Neale, 2005).

Iconography in the context of genre films refers to the visual symbols, images, and motifs that are characteristic of a particular genre. These visual elements often convey specific meanings and help establish the identity of a genre. In horror films, common iconographic elements might include dark settings, eerie music, monsters, and symbols associated with fear. In science fiction, futuristic technology, space settings, and advanced gadgets are frequently used as iconographic elements. Iconography serves to quickly convey genre expectations to the audience. It creates a visual language that audiences recognize and associate with specific genres, contributing to the overall atmosphere and thematic elements of the film.

Ideology in the context of genre films refers to the underlying beliefs, values, and worldview that are often present in the narrative. It reflects the cultural, social, and political perspectives that shape the story and characters. Action films often promote values such as heroism, justice, and individual agency. In romantic comedies, themes of love, relationships, and personal fulfillment are commonly explored. Ideology can also involve underlying messages about gender, race, or societal norms. Ideology in genre films shapes the narrative and characters, influencing the way the story is told and the messages it conveys. It allows filmmakers to explore and communicate specific cultural or societal ideas within the context of a particular genre.

Narrative in genre films refers to the storytelling structure, plot, and character development. Different genres often have distinct narrative conventions, including specific plot arcs, character roles, and thematic elements. In a crime thriller, the narrative might revolve around solving a mystery, with plot twists and suspenseful moments. In a romantic comedy, the narrative could follow the ups and downs of a romantic relationship, often with humor and a happy resolution. The narrative structure is crucial for engaging the audience and delivering the genre-specific experience. It helps set expectations for the progression of the story and the resolution of conflicts. Effective storytelling within a genre enhances the overall impact of the film on the audience. In summary, iconography, ideology, and narrative are interconnected elements in genre films. Iconography establishes the visual language of a genre, ideology shapes the underlying beliefs and values, and narrative structures the storytelling to create a cohesive and recognizable genre experience for the audience. These components work together to define, communicate, and explore the unique qualities of different film genres (Neale, 2005; Mac Donald, 2007, Altman, 2012, Slugan, 2022).

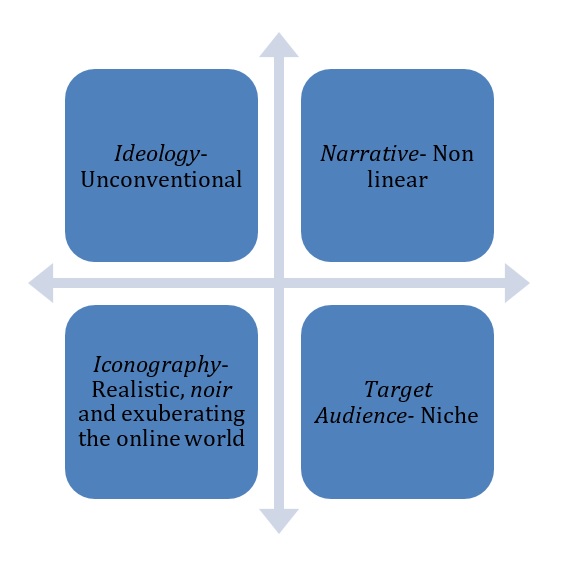

Fig 1: The Genre characteristics of an OTT Film in India

Films that investigate the realm of social media offer intriguing glimpses into the complexities of modern communication and interaction. One standout example is The Social Network (Fincher, 2010) which provides a gripping portrayal of the rise of Facebook and its founder, Mark Zuckerberg. The film looks into the intricacies of entrepreneurship, personal relationships, and the transformative power of social networking platforms. Another thought-provoking documentary, Catfish (Shulman & Joost, 2010), explores the deceptive nature of online identities and the potential dangers lurking behind social media facades. Meanwhile, Pirates of Silicon Valley (Burke, 1999) offers a historical perspective on the rivalry between tech giants Apple and Microsoft, shedding light on the innovation and competition that shaped the digital landscape. These films, along with others like Hackers (Softley, 1995) and Julie & Julia (Ephron, 2009), paint a vivid picture of the profound impact of social media on society, from its thrilling possibilities to its darker complexities. Through compelling narratives and compelling characters, these movies navigate the intricate web of human connections in the digital age, inviting audiences to ponder the ever-evolving intersection of technology and humanity. (Montti, 2022; Vimalan, 2014).

Fig 2: Poster of Kho Gaye Hum Kahan[10]

Analyzing Kho Gaye Hum Kahan through Genre theory

‘It’s the digital age sirf lagta hai zyada connected hai lekin shayad itne akele pehle kabhi nahi the. – Simran (Kalki Koechlin)[11]

‘Hum sab social media pe sirf aur sirf show off karte hain.’-Imaad Ali (Siddhant Chaturvedi)[12]

This film is a thought-provoking observation on the paradox of the digital era: despite the sense of heightened connectivity, there is an underlying loneliness. The creators convey this insight earnestly, tailored for the Instagram generation, as depicted in Kho Gaye Hum Kahaan, featuring young and trendy actors like Siddhant Chaturvedi, Ananya Pandey and Adarsh Gourav, and others, perfectly encapsulating the world of the Insta generation. The narrative revolves around the lives of Mumbai-based best friends Imaad (Siddhant), Ahana (Ananya), and Neil (Adarsh) as they navigate the challenges of adulthood. Imaad, immersed in Tinder, grapples with personal issues, while Ahana seeks attention from her commitment-phobic boyfriend. Neil, aspiring to escape his middle-class life, hopes that a workout selfie with a celebrity will elevate his social media presence. The ensemble cast exudes a visually pleasing, casually ruffled vibe, seamlessly blending English and Hindi in their dialogues.

The film’s title suggests an exploration of the Farhan-Zoya[13] universe, depicting confused youth transitioning into adulthood. However, these characters are deeply entrenched in the digital age, relying on their phones for companionship, validation, and connection. The film appears almost tailor-made for a mobile viewing experience. The writing strives for inoffensiveness, incorporating mild humor and sporadic attempts at depth. Moments addressing issues like classism and the consequences of seeking closure are notable. The film aligns itself with contemporary drama, exploring the complexities of modern relationships. It incorporates elements of romantic comedy and coming-of-age genres, utilizing a diverse ensemble cast to portray the nuances of interpersonal connections in the digital age. The blending of English and Hindi in dialogues adds a multicultural layer to the narrative, reflecting the cultural diversity of the characters’ urban experiences. Despite its attempts to navigate relevant social issues, the film falls short of providing a cohesive and impactful storyline, potentially leaving viewers with a sense of unfulfilled expectations. (Desk, 2023; Gupta, 2023)

KGHK[14] is a film which falls in the category of social media films, the ideology of such films deals with the effects of social media on our lives, how digital communication changes us; the film asks existential questions on the presence of social media in our lives; other such films in India which have dealt with the topic of social media include Bajrangi Bhaijaan (Khan, 2015); Mujse Fraandship Karoge (Asthana, 2011) and Secret Superstar (Chandan, 2017). The misc en scene of the film brings out the varied spaces of Mumbai, from a middle class crunched one BHK to a plush studio apartment to a live-in space; Mumbai is seen in its various unpredictable colors; Singh (2024) mentions how he wanted to pay a tribute to the city by the spaces shown in the film, the city of 1990s with simpler buildings and gentry of mixed classes; he wanted Bandra and its cosmopolitan life to be emphasized and give a nostalgic feel of old Bombay. Its characters and their dialogues are well etched, Imaad and his Hideout standup comedy place gives a tangibility to his childhood fears and his dialogues are a sarcastic cushion to his insecurities. Ahana defines every-one of us who is glued to social media and stalks friends and family and needs to come out of the social media insecurities and accept life as it is. Neil is a middle class boy aspirational for a better life and the inclusion of social media in his emotional entanglements and his fall as a human and the redemption that comes in the end. The three characters are from different spaces of Mumbai but their lives are intersected by their friendship and the social media connection. Narrative of the film flows simply and gives us moments to reflect at the lives of Gen Z; it’s a simply told of intertwined life of three Gen Zeers’ but the themes and underlying messages are existential.

Conventional Masala Film and the Rasa Theory

Rasa theory, originating from classical Indian aesthetics and most notably associated with Bharata Muni’s Natya Shastra[15], is a concept that explores the emotional impact of art and performance, including its application to films. Rasa, in Sanskrit, translates to essence or flavor. The theory suggests that a successful work of art, including film, should evoke specific emotional responses in the audience. According to Rasa theory, there are nine fundamental emotions or sentiments, known as Navarasa. These are:

Shringara (Love/Beauty)

Hasya (Laughter)

Karuna (Sorrow)

Raudra (Anger)

Veera (Courage)

Bhayanaka (Fear)

Bibhatsa (Disgust)

Adbhuta (Surprise/Wonder)

Shanta (Peace/Tranquility)

The ultimate goal of art, according to Rasa theory, is to evoke a specific dominant emotion or mood (Rasa) in the audience. Each piece of art, including films, is said to have a specific Rasa that it aims to convey. Bhavas are the psychological and emotional states that contribute to the overall mood or Rasa of a performance or work of art. They are expressed through facial expressions, body language, and other artistic elements. Sthayi Bhava refers to the primary or dominant emotional state that persists throughout a performance or work of art. Vyabhichari Bhava are transient emotions or moods that complement and enhance the Sthayi Bhava. They help in the overall development of the emotional experience. The audience is considered an active participant in the creation of Rasa. It is believed that the artist’s expression and the audience’s receptivity together contribute to the evocation of the desired emotional experience. In the context of films, directors and filmmakers can apply Rasa theory by carefully crafting scenes, dialogue, music, and visual elements to evoke specific emotions. Different genres and types of films may aim to generate various Rasas, depending on the intended impact on the audience. Rasa theory provides a framework for understanding the emotional power of cinema and how it can resonate with viewers on a deep, visceral level (Booth, 1995; Hogan, 2009; Jones, 2009; Roy, 2017).

Panch ghante chalne wali mosquito coil ke liye kitne sawaal karte ho…lekin panch saal tak apni SARKAAR chunte waqt ek SAWAAL nahi karte, kuch nahi poochte.[16]– Azad (SRK)

Main hu Bharat ka naagrik. Baar baar naye logo ko vote deta hu, lekin kuch nahi badalta hu.[17]– Azad (SRK)

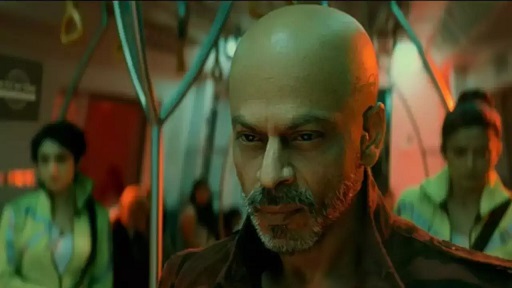

Fig 3: SRK in a still from Jawaan[18]

The film Jawan starts with a striking opening sequence set along India’s northern borders, depicting the remarkable recovery of a wounded soldier amidst a sudden and intense attack on a peaceful village. The soldier, emerging as a messianic figure, wields a spear against a dramatic sky in a grand, mythical scene shrouded in darkness, featuring even a flaming horse evoking Adbhuta rasa. Notably, the film has been compared to the style of Japanese video game designer Hideo Kojima[19], marking it as Shah Rukh Khan’s most Metal Gear-inspired film. Directed by Atlee, a Tamil filmmaker renowned for collaborating with Southern directors on Bollywood action films, the narrative suggests complex characters with multiple identities. Atlee’s inclination towards stories involving fathers and sons aligns seamlessly with Khan’s history of excelling in multiple-role films. The storyline fast-forwards 30 years, introducing Khan as a quirky vigilante leading a team of female fighters to hijack a Mumbai metro train. The plot unveils Khan’s character, Azad Rathore, as an ethical terrorist who moonlights as a high-security women’s prison jailer. His present-day mission involves marrying Nayanthara’s character, Narmada, a negotiator from the hijack incident.

Jawan pushes the boundaries of Khan’s superstar repertoire, showcasing him in diverse roles, from a benevolent citizen to a grizzled, cigar-chomping character reminiscent of Wolverine. The action sequences in Jawan are lauded as slick and Hollywood-style, featuring drones, choppers, and gatling guns. Atlee infuses Indian elements into these set pieces, such as a hijacker escaping in an auto-rickshaw and a flashback with Deepika Padukone slamming Khan in the mud. The film also addresses social justice issues, with Khan launching a Clean India campaign and challenging faulty institutions. Jawan has movie references, encompassing both Bollywood and Hollywood giving intertextuality and depth to the film (Mishra, 2009). Fans are expected to enjoy spotting references to various films, including Khan’s own works like Main Hoon Na (2004, Khan), Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi (2008, Chopra), and Duplicate (Bhatt, 1998). While certain elements, like Atlee-esque melodrama and generic songs, may not resonate universally, performances from Vijay Sethupathi and Nayanthara receive acclaim creating a film which is infused in masala elements of typical Bollywood tradition evoking adbhuta rasa with the characters of father and son- Vikram and Azad , Bibhasta rasa is evoked with Vijay Sethupati’s characters’ ruthlessness (Kalee Gaikwad); Bhayanak and karuna rasa are evoked simultaneously at the same time with sequences depicting the sad story of all the brave women characters (Halena, Laxmi and Dr Eram) in Azad’s team (Mitra, 2023; Mukherjee, 2023).

In a Rasa analysis of the film several key elements contribute to the viewer’s perception and understanding of the narrative. The film employs visual and narrative techniques to engage the audience and convey its underlying themes. The opening sequence, set along India’s northern borders, establishes a vivid and dramatic backdrop for the story. The wounded soldier’s recovery and emergence as a messianic figure create a veer rasa moment for the audience. The use of a spear, dramatic sky, and a flaming horse adds mythical and symbolic layers, engaging the viewer’s cognitive processes in deciphering potential meanings. The opening scene creates a Bhibatsa and Shaurya rasa evoking performance. Director Atlee’s collaboration with Southern directors influences the cognitive reception of character complexities. The narrative hints at multiple identities, aligning with Atlee’s penchant for stories involving fathers and sons. This cognitive layer prompts the audience to explore the connections between characters, especially Shah Rukh Khan’s various roles, and enhances the film’s puzzle-like nature. A lot in the film points towards the typical masala nature of it. Larger than life characters, grand sets and open shooting spaces, emotional potpourri- the father son story, the typical sacrificial mother who has been coincidentally named Kaveri Amma to bring intertextuality from other SRK films (Here, Swades (Gowarikar, 2004)); the song and dance sequences, the messiah[20] or the angry young man of the 1970s surfacing interchangeably through Azad and Vikram Rathore’s characters. The names pointing towards ideologies they have in life and creating intertextuality with old Hindi films and in the process paying tribute to them. The last dialogue where SRK speaks to the audience and encourages them to be a conscious citizen; the kidnapping scene before it and the tear jerking Padukone subplot; there is no dearth of melodrama (Prasad, 2000) in this film. We get to see a lot of emotions, multiple plots, larger than life characters, digressions, and simplification of complex concepts giving the film a typical masala character.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research paper critiques the dynamic evolution of Indian cinema, tracing its rich history from the early days of Phalke’s desi cinema to the contemporary landscape dominated by mainstream Bollywood productions. The emergence of Over-The-Top (OTT) cinema marks a significant paradigm shift, challenging conventional norms and opening new horizons for storytelling. The juxtaposition of Shahrukh Khan’s blockbuster comeback films like Jawaan and Pathaan with niche OTT releases such as Jaane Jaan and Kho Gaye Hum Kahan highlights the coexistence of diverse cinematic traditions in India.

The paper explores the inception of OTT cinema, identifying factors like the survival imperative during the Covid times, technological advancements, medium characteristics, niche audiences, and the freedom to experiment with storytelling as catalysts for this cinematic revolution. It underlines the stark differences not only in the narratives, characters, and storytelling methods of mainstream Bollywood films and OTT releases but also in the platforms they are released on and the reception they garner. The age-old tradition of Hindi cinema, with its roots in myth and folklore, genre-less narratives, star power, and industry verisimilitude, is juxtaposed against the fresh and unconventional nature of OTT Indian cinema. The research paper critiques this transformation chronologically, offering insights into how the two cinematic traditions coexist and complement each other. It emphasizes that while Hindi cinema has a well-established identity, OTT Indian cinema is still carving its niche by challenging mainstream cinema norms and assumptions.

The comparative analysis between the typical Bollywood masala film Jawaan and the OTT release Kho Gaye Hum Kahan serves as a microcosm of the broader cinematic landscape. It provides a lens through which to understand the shifts in content strategy, budgeting, and narrative choices, reflecting the evolving tastes of the audience and the dynamic nature of the film industry. In essence, this research paper contributes to the ongoing discourse on Indian cinema by unraveling the intricacies of its transformation. It underscores the importance of acknowledging and studying the coexistence of traditional and emerging cinematic forms, shedding light on how both contribute to the vibrancy and diversity of India’s cinematic heritage.

In spite of the insightful exploration into the evolution of Indian cinema and the emergence of OTT platforms, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations within the scope of this research. The paper primarily focuses on a select set of films, such as Jawaan and Kho Gaye Hum Kahan, which might not represent the entirety of Bollywood or OTT content. A more comprehensive analysis could be achieved by including a broader range of films and genres, considering the vast and diverse landscape of Indian cinema. Furthermore, the paper largely discusses Indian cinema in a broad sense, and a future avenue of exploration could involve a more in-depth analysis of regional cinemas and their unique contributions to the evolving narrative of Indian storytelling. Regional nuances often play a significant role in shaping cinematic identities, and a focused study on specific regional cinemas would add depth to the understanding of India’s cinematic diversity.

As the film industry continues to evolve, with advancements in technology, changing audience demographics, and global collaborations, future research could investigate into the impact of these factors on content creation, distribution, and reception. Understanding how the interplay of global and local influences shapes the narratives and production values of Indian films could provide valuable insights into the industry’s trajectory. In conclusion, while this research sheds light on the transformative journey of Indian cinema and the disruptive influence of OTT platforms, there exist opportunities for more nuanced investigations. Exploring a wider array of films, probing into specific regional cinemas, and conducting in-depth analyses of the socio-cultural and technological facets could enrich our understanding of the intricate arras that is Indian cinema.

REFERENCES

- Altman, R. (2012). A semantic/syntactic approach to film genre. In B. Grant (Ed.), Film genre reader IV (pp. 42-62). University of Texas Press.

- Booth, G. D. (1995). Traditional Content and Narrative Structure in the Hindi Commercial Cinema. Asian Folklore Studies, 54(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178940

- Banaji, S. (2006). Young people viewing Hindi films: Ideology, pleasure and meaning. In A. Karim (Ed.), Media and communication in the Indian context (pp. 271-289). Routledge

- Chatterjee, M., & Pal, S. (2020). Globalization propelled technology often ends up in its micro-localization: Cinema viewing in the time of OTT. Global Media Journal-Indian Edition, 12(1), 1.

- Das Gupta, C. (2008). Seeing is Believing: Selected Writings on Cinema. India: Penguin Viking.

- Dwyer, R. (2014). Bollywood’s India: Hindi Cinema as a Guide to Contemporary India. United Kingdom: Reaktion Books.

- Drennan, M., & Baranovsky, V. (2018, January 1). Scriptwriting for Web Series. Focal Press. http://books.google.ie/books?id=IxFbswEACAAJ&dq=Scriptwriting+for+web+series:+Writing+for+the+Digital+age.+Routledge.&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api

- Desk, H. E. (2023, December 25). Kho Gaye Hum Kahan celeb review: Aditya Roy Kapur, Ishaan Khatter heap praises. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/entertainment/bollywood/kho-gaye-hum-kahan-celeb-review-aditya-roy-kapur-recommends-girlfriend-ananyas-film-ex-ishaan-khatter-praises-it-too-101703489922479.html

- Desk, T. L. (2024, January 2). Kho Gaye Hum Kahan: 5 Lessons On Life, Love In A Digital Age. TimesNow. https://www.timesnownews.com/lifestyle/relationships/love-sex/kho-gaye-hum-kahan-5-lessons-on-life-love-in-a-digital-age-article-106480864

- Fitzgerald, S. (2019). Over-the-Top Video Services in India: Media Imperialism after Globalization. Media Industries, 6(2). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mij/15031809.0006.206/–over-the-top-video-services-in-india-media-imperialism-after?rgn=main;view=fulltext

- FICCI FRAMES REPORT 2023. (2023, April). In FICCI FRAMES. FICCI. Retrieved February 22, 2024, from https://www.ficci-frames.com/reports.html

- Ganti, T. (2013). Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema. United Kingdom: Routledge.

- Gupta, S. (2023, December 26). Kho Gaye Hum Kahan movie review: Siddhant Chaturvedi, Ananya Panday, Adarsh Gourav film is for Insta generation, by Insta generation. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/entertainment/movie-review/kho-gaye-hum-kahan-movie-review-siddhant-chaturvedi-ananya-panday-adarsh-gourav-film-for-insta-generation-9083229/

- Hogan, Patrick Colm (2009). Hindi cinema as a challenge to film theory and criticism. Projections 3.2 ,pp- 5-9.

- Kohli-Khandekar, V. (2021). The Indian Media Business: Pandemic and After. India: SAGE Publications India Pvt, Limited.

- McDonald, T. J. (2007). Romantic comedy: boy meets girl meets genre. United Kingdom: Wallflower.

- Malhotra, S., & Alagh, T. (2004). Dreaming the nation: Domestic dramas in Hindi films post-1990. South Asian Popular Culture, 2(1), 19-37.

- Moochhala, Quresh (2018). The future of online OTT entertainment services in India. Actionesque Consulting, Pune–India

- Mishra, V. (2013). Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire. United States: Taylor & Francis.

- Matthew Jones (2009) Bollywood, Rasa and Indian Cinema: Misconceptions, Meanings and Millionaire. Visual Anthropology. 23:1, 33-43, DOI: 10.1080/08949460903368895

- Madhukalya, A. (2023, December 29). Shah Rukh Khan’s 2023 releases ‘Dunki’, ‘Pathaan’, ‘Jawan’ made Rs 2,500 crore. and counting. Business Today. https://www.businesstoday.in/trending/box-office/story/shah-rukh-khans-2023-releases-dunki-pathaan-jawan-made-rs-2500-croreand-counting-411277-2023-12-29

- Mitra, S. (2023, September 7). ‘Jawan’ movie review: Shah Rukh Khan is spectacular in Atlee’s socially-charged thriller. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/movies/jawan-movie-review-shah-rukh-khan-is-spectacular-in-atlees-socially-charged-thriller/article67277788.ece

- McCahill, M. (2023, September 8). Jawan review – Shah Rukh Khan vehicle goes like a runaway train. The Guardian.

- Montti, R. (2022, November 8). 25 Top Movies About Social Media To Watch. Search Engine Journal. https://www.searchenginejournal.com/social-media-movies/313503/

- Mishra, P., & Mishra, P. (2023, December 26). “Kho Gaye Hum Kahan” Review: This Gen Z Tale Is Smart & Full of Heart. The Quint. https://www.thequint.com/entertainment/movie-reviews/kho-gaye-hum-kahan-zoya-akhtar-tiger-baby-full-film-review-movie-siddhant-chaturvedi-ananya-panday-latest-adarsh-gourav-netflix#read-more

- Mishra, V. (2009, June). Spectres of Sentimentality: the Bollywood Film. Textual Practice, 23(3), 439–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502360902868399

- Nijhawan, G. S., & Dahiya, S. (2020). Role of COVID as a catalyst in increasing adoption of OTTs in India: A study of evolving consumer consumption patterns and future business scope. Journal of Content, Community & Communication, 12(6), 298. doi: 10.31620/JCCC.12.20/28

- Neale, S. (2005). Genre and Hollywood. Taylor & Francis.

- Netflix’s Monika Shergill on understanding audiences, stories and the storytelling journey. (2021, May 6). Afaqs! https://www.afaqs.com/news/media/netflixs-monika-shergill-on-understanding-audiences-stories-and-the-storytelling-journey

- Partho Dasgupta – Change in the strategy of OTT platforms needed to succeed in India. (2022, August 18). Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/content/specials/partho-dasgupta-change-in-the-strategy-of-ott-platforms-needed-to-succeed-in-india-122081700945_1.htmlPrasad, M. M. (2000).

- Prasad (2000). Ideology of the Hindi Film: A Historical Construction. India: Oxford University Press.

- Rajadhyaksha, A. (2016). Indian Cinema: A Very Short Introduction. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Rajadhyaksha, A. (2015). The ‘Bollywoodization’of the Indian cinema: Cultural nationalism in a global arena. In The Inter-Asia Cultural Studies Reader (pp. 465-482). Routledge.

- Roy, Piyush (2022). Appreciating Melodrama: Theory and Practice in Indian Cinema and Television. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Roy, S. (2023, April 23). OTT in India: A New Wave of Cinema – Spandita Roy – Medium. Medium. https://medium.com/@spanditaroy03/ott-in-india-a-new-wave-of-cinema-dedb39b62256

- Rao, J. J. (2024, January 9). Director Arjun Varain Singh on Kho Gaye Hum Kahan; platonic friendship, sequel and how he mounted film as love letter to vintage Bombay. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/entertainment/bollywood/director-arjun-varain-singh-on-kho-gaye-hum-kahans-refreshing-platonic-friendship-sequel-ananya-panday-9101122/

- Sundaravel, E., and N. Elangovan. Emergence and future of Over-the-top (OTT) video services in India: An analytical research. International Journal of Business, Management and Social Research 8.2 (2020): 489-499.

- Samala Nagaraj, Soumya Singh, & Venkat Reddy Yasa. (2021). Factors affecting consumers’ willingness to subscribe to over-the-top (OTT) video streaming services in India. Technology in Society. Retrieved from http://www.elsevier.com/locate/techsoc

- Srinivas, L. (2002). The active audience: spectatorship, social relations and the experience of cinema in India. Media, Culture & Society, 24, 155–173.

- Slugan, Mario. (2022). Pandemic (Movies): A pragmatic analysis of a nascent genre. Quarterly Review of Film and Video 39.4 T. M., & T. M. (2023, September 23).

- Is Jawan a Political Film? Film-companion. https://www.filmcompanion.in/features/bollywood-features/is-jawan-a-political-film-shah-rukh-khan-atlee

- Thomas, R. (1985, May 1). Indian Cinema: Pleasures and Popularity. Screen, 26(3–4), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/26.3-4.116

- Vasudevan, R. S., Thomas, R., Srinivas, S. V., Siddique, S., Mukherjee, D., Nair, K., & Hoek, L. (2023, December). Cinema in the Age of Social Media. BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies, 14(2), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/09749276231215876

- Vasudevan, R. (2014, September 12). the meanings of bollywood. Csds. https://www.academia.edu/8278215/the_meanings_of_bollywood

- Vasudevan, R. S., Thomas, R., Srinivas, S. V., Siddique, S., Mukherjee, D., Nair, K., & Hoek, L. (2023, December). Cinema in the Age of Social Media. BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies, 14(2), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/09749276231215876

- Vimalan, P. (2014, February 19). 8 Must Watch Movies Based on Social Media! SocialSamosa. https://www.socialsamosa.com/2014/02/movies-based-social-media/

- Wright, N. S. (2015). Bollywood and Postmodernism: Popular Indian Cinema in the 21st Century. United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press.

[1] A potpourri of spices

[2] Indigenous

[3] Films that were different from typical Bollywood commercial films, like the films of Anurag Kashyap and Vishal Bhardwaj

[4] Indian OTT Cinema or OTT Hindi Cinema here means the Indian cinema films released exclusively on OTT

[5] ShahRukh Khan

[6] The passing down of traditions or values from one generation to the next, or the process by which they are transmitted through time.

[7] In the 1970s , the characters that were created for Amitabh Bachchan, by screenwriters, especially the duo Salim-Javed was of the superhero subaltern hero against the corrupt system; a mention of this era is made in seminal studies like Ganti’s, Prasad’s as well as Mishra’s.

[8] Gupta at length describes the difference between commercial and art cinema in Seeing is Believing (2008)

[9] Ashish Rajadhakshya (2016) explains the first two big bangs as Phalkes inception of desi cinema and Satyajit Ray’s release of Pather Panchali (1955) as the interface of Indian cinema with the world on a critical stage

[10] Film : Kho Gaye Hum Kahan. (2023, December 26). Imdb. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt15434074/

[11] It’s the digital age; it just seems like we’re more connected, but perhaps we’ve never been so alone before.

[12]We all just show off on social media

[13] Farhan Akhter and Zoya Akhter have made films which represent Cosmopolitan youth and their dilemmas

[14] Kho Gye Hum Kahan

[15] The Natyashastra is an extensive guide and manual for theatrical artistry, encompassing every facet of classical Sanskrit drama. Traditionally attributed to the legendary Brahman sage and priest Bharata, believed to have lived between the 1st century BCE and the 3rd century CE.

[16] Elect your representatives wisely during elections

[17] I am an Indian , my vote holds no power

[18] A still from Jawaan. (2023). Times Now. https://www.timesnownews.com/entertainment-news/jawan-prevue-fan-reactions-shah-rukh-khan-atlee-film-with-nayanthara-deepika-padukone-is-going-to-be-a-hit-bollywood-news-article-101632059

[19] Born on August 24, 1963, Hideo Kojima is a prominent Japanese video game designer celebrated as a visionary of the medium. Fostering a deep love for cinema and literature since his early years, Kojima’s journey into the realm of video game creation began when he joined Konami in 1986. It was there that he crafted his seminal work, Metal Gear (1987), for the MSX2 platform, which not only pioneered the stealth genre but also laid the cornerstone for the acclaimed Metal Gear series, marking the zenith of his creative endeavors.

[20] Help from divine

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.